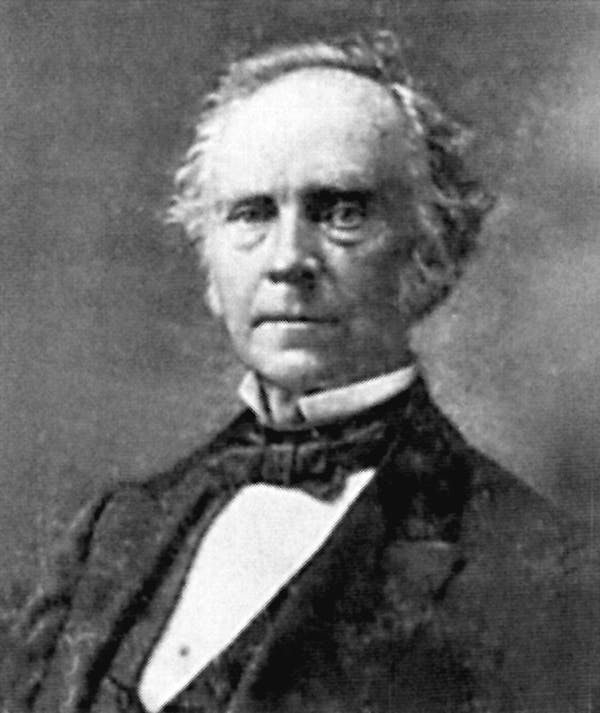

Andrews, Samuel

1996 - Standard Oil Co.

Samuel Andrews (1836-1904) worked with John D. Rockefeller at Standard Oil.

The greatest house built on Euclid Avenue's fabled "Millionaires' Row" did not belong to one of Cleveland's two most powerful men, John D. Rockefeller or Marcus A. Hanna. That honor goes to one of Rockefeller's early partners, Samuel Andrews.

A poor Englishman by birth, Andrews somehow envisioned that Britain's Queen Victoria might one day need a place to stay and be entertained in Cleveland. So he built a mammoth Victorian Gothic mansion on a lot at the northeast corner of Euclid Avenue and Sterling Street (now East 30th Street). The studios and offices of WEWS-TV now occupy the site, along with several other buildings to the east and north.

Andrews arrived in Cleveland in 1857 from Wiltshire, England, where he had been a candle-maker. One biographer described him as a "big, ruddy, kindly man with expressive eyes."

An earlier arrival from his hometown, Maurice Clark, got the 21-year-old Andrews a job in a lard-oil refinery, where he became an expert in refining lard into tallow for candles. Andrews then began to extract lamp oil from coal and eventually his employer, Charles Dean, had 10 barrels of petroleum shipped to Cleveland from the first oil fields of Pennsylvania. Andrews was the first in Cleveland to master the chemistry of refining kerosene from petroleum.

Seeing the possibilities of this new lighting fuel (the automobile hadn't been invented yet), Andrews in 1862 went to his patron, Clark, and Clark's partner in the wholesale grain and produce business, Rockefeller, to discuss the commercial possibilities of petroleum refining.

Clark and Rockefeller had also been mulling the opportunities in oil refining. It helped that Rockefeller knew Andrews from the Erie Street Baptist Church and respected his thrift and hard work.

Out of these early discussions came Andrews, Clark & Co. Andrews became superintendent of the refinery they built and his expertise in squeezing the last drop of refined product out of a barrel of crude oil gave the company an early competitive advantage.

When the business reorganized as Standard Oil Co. in 1870, Andrews had a 13.3 percent interest, to Rockefeller's 26.7 percent. By 1874, Andrews wanted out. Though a substantial shareholder and an employee of Standard Oil, he was not a top executive. Rockefeller biographer Allan Nevins said Andrews was a technician who "had not kept pace with his associates." When he grumbled that the company was plowing most of its profits back into the business rather than into dividends, Rockefeller offered to buy him out and asked Andrews for a price. Andrews suggested $1 million and Rockefeller had a check for him the next day.

Though now a wealthy man, Andrews went to work for American Steel & Wire Co. He also put his time and money into several local organizations, notably Brooks Military School, which operated in the last quarter of the 19th century.

In 1882, after putting several architects on the project, he started construction on his 18,000-square-foot home on Millionaires' Row. As one author noted, Andrews "had a flair for the unreasonable and his new home was no exception."

The sandstone house had 33 rooms by some accounts, including six ballroom-sized rooms on the first floor finished with hand-carved wooden paneling surrounding a skylighted spiral staircase. There were five suites, one for each of the Andrews' daughters on the second floor. Above that was a vast ballroom/auditorium and servants quarters. The Andrews lived on Euclid for only four years before moving to New York City. The home stood empty, but was maintained, for 30 years before it was tom down. Even before it was completed it came to be called "Andrews Folly."

In 1921, a movie company, the Bradley Feature Film Co., took over the house and made three early films, "House Without Children," "Women in Love" and "Dangerous Toys" in the mansion.

Andrews Folly was razed in 1923.

Written by Jay Miller

)