Nov. 11, 2018: Interrogation Room, Wise County Detention Center. Decatur, Texas.

He called them “grapes,” objects for his consumption.

He laughed out loud as he said it, as if it were a joke, “How many grapes y’all got on the vine here?” Those hands made a plucking motion. He chuckled again.

He picked them in the slums and run-down places, the places society ignored, the places where no one trusted police. Places like Cleveland.

“The police don’t know, they ridin’ around, sh--,” he said. “As long as you didn’t get in f---ing around out there with the people who would be immediately missed and very important to either family or babies or somebody.”

He remembered their faces, but rarely knew their names. He remembered his cars better. He drove them from city to city, paying his way with day labor and petty crime.

He lured the women with promises of money or drugs. Most he hired. Others he seduced. He never used a gun or knife. Always, he used his hands.

“You got pretty good at knowing which ones —” said one interrogator.

“Yeah, I’m not gonna go over there in the white neighborhood and pick out a little, young teenage girl,” he said. “I ain’t gonna go over there and pick out a housewife while she’s out there with the shopping in her hands and drag her to the car while she’s …”

He mimicked a woman screaming.

“That’s the kind you get busted for.”

Her name was Rose.

She was Pam Smith’s sister.

Growing up in the ’60s, Pam and Rose were close, despite the five years that separated them. Everyone said they looked alike. They watched movies together, walked the streets of Binghamton, New York, together, grew up far too fast together. They skipped school. They drank. They caroused. They got in trouble. Pam worried Rose was partying too hard. But it was like everyone said: They were a pair of peas.

After she turned 16, Rose disappeared. She took a trip to Cleveland with two friends. The friends came back. Rose didn’t. Pam was devastated. At least every six or so months, Rose would call.

“When are you coming back home?” Pam would ask.

“I don’t think I’m staying here,” Rose would say.

But for more than a decade, Rose stayed.

As the years passed Pam could tell, even through the phone, that Rose was doing drugs. Crack was everywhere in the late ’80s. For money, Rose said she was a sex worker. She had met a man too, and said she got married. She was Rose Evans now.

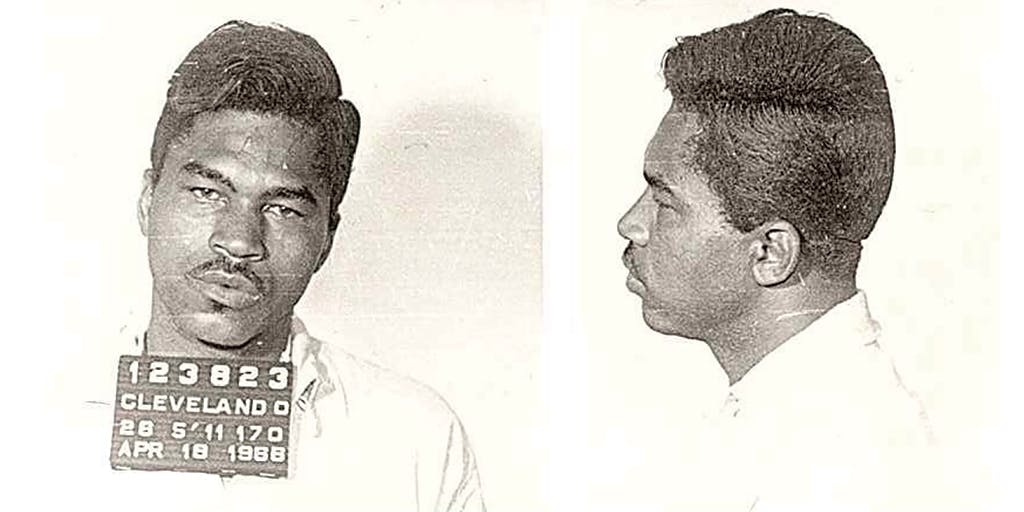

In January 1990, Rose was arrested on a drug charge in Cleveland. She was booked into jail twice more that year. In one police photo, her gray eyes were defiant. Her hair was tightened into braids. She wore a red and white shirt sporting a cartoon character. “Nobody’s Perfect,” it said. “And I’m a Perfect Example!”

Rose visited Pam in Binghamton that year, a brief stopover while she was on a two-day trip. Pam remembers Rose was traveling with a man. He said hello, but didn’t leave the car. “That was the last time I saw her,” Pam says. The next thing she remembers is two plainclothes detectives on her mother’s doorstep.

On Aug. 24, 1991, a man walking through a field on East 39th Street found Rose around 7:40 a.m. She was facedown and covered, evidently with haste, by two large truck tires. She wore a royal blue shirt, jeans and white canvas shoes. Detectives identified her by the contents of her pockets: her welfare card, her medical card and two prescriptions. There was blood on her upper lip and nose. The coroner determined she had been strangled. Drag marks had furrowed the dirt leading up to where she had been placed. They started near the curb, where detectives photographed a set of large tire marks.

The police conducted interview after interview. They talked to owners of businesses near the crime scene, past and current roommates, Rose’s father-in-law (her husband was in jail), neighbors who knew Rose’s boyfriend (her boyfriend was also in jail), Rose’s friends. They interviewed the 85-year-old man Rose had been crashing with at the Phillis Wheatley Association home. He said he felt sorry for her. He let her stay for free.

They canvassed the local motels, interviewing an employee at one on East 40th Street who had reported the body. She identified Rose as a working girl. A man had come in to say he’d seen her in the field, and the worker had called the police. The manager of an East 55th Street motel recognized her too, saying he had seen her the day before she died.

The interviews turned up more promising leads. In January 1992, a working girl showed up at Charity Hospital after being assaulted. She told police she’d been smoking crack with Rose the night she disappeared, and had seen her get into a two-door, burgundy car with a black man between 3 and 4 a.m.

The woman also said that around that time, in September or October 1991, a man had raped her and tried to strangle her with a rope. In the police report, she said someone was “raping and beating the strawberrys [sic] and it is not being reported.” A detective gave the woman a card and said to call if she saw the car again.

Police considered several suspects, but no one was charged in Rose’s death. Her case was entered into the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program database, which tracks unsolved homicides. Pam can’t remember ever getting an update about the case.

Pam heard nothing from police for more than two decades. The family couldn’t afford a burial, so Rose was cremated. They couldn’t afford an urn either, so, for 10 years, Pam kept Rose’s ashes in a small box. She took it with her when she moved to a small town outside Scranton, Pennsylvania. One day, she took it out to a creek. She waded out into the water and spread Rose’s ashes, letting the flow take her away. “You can’t live like that, in a cardboard box,” she says. “I just said, ‘Fly away and be happy.’ ”

He thought we would only remember the women like he did. Faces without names. Names without stories.