A CWRU Researcher Creates the Sense of Touch

by Kevin Stankiewicz | Sep. 14, 2016 | 2:00 PM

Evan Prunty

Dustin Tyler always gets the same feeling.

Whenever the Case Western Reserve University professor and researcher sees something that doesn’t work, an urge drives him to fix it.

“I like working at the things that don’t exist and trying to make them exist,” Tyler says.

After nearly 10 years of research, he did that for Igor Spetic, who lost his right forearm and hand in a manufacturing accident and had been using two prosthetics.

While more complex, upper extremity prosthetics are less functional than leg prosthetics. Without the sense of touch to know how hard to squeeze a tomato while cutting it or how much to pinch your fingers together to pick up a penny, most prosthetic hands end up on closet shelves, says Tyler.

“We don’t really realize how much we rely on sensory feedback until we lose it,” he says.

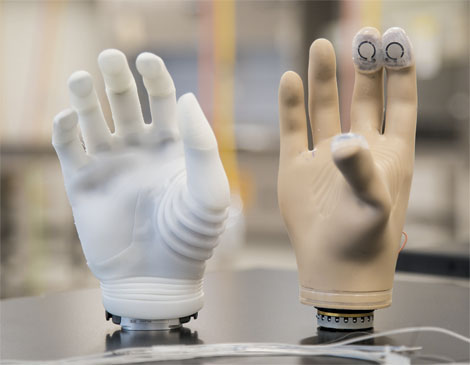

Using a system of surgically implanted electrodes around nerves in the upper arm, which communicates to a prosthetic hand with moveable fingers with sensors in them, Tyler was able to give Spetic a sense of something he hadn’t felt in years.

“Wow, that’s my thumb,” Tyler recalls Spetic saying. “I haven’t felt my thumb since the accident.”

Tyler graduated from CWRU in 1999 with a doctorate in biomedical engineering and tried his hand at the private sector. But his ambition for making far-off concepts real didn’t work in a corporate environment.

“In the commercial sector, you have to be on a three-year timeline for the return on investment,” Tyler says. “What I really was missing was the idea to look forward to projects that were five, 10, 15 years out before they became commercial.”

An article in Science journal about research looking into the ways cells process information piqued his creative nerves. He took a position as a researcher at the Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center in partnership with CWRU and MetroHealth Medical Center to study the nervous system and how to communicate with it.

His early work involved treating spinal-cord injuries and stroke recovery, both of which involved muscle stimulation to advance rehabilitation — essentially making the muscles work again.

“But we had yet to engage in the other way: where we put information back into the system,” Tyler says. “To the brain, to the sensory side.”

Tyler offers a Robin Williams-like grin when he talks about his current project’s advances in communicating with the nervous system. But he and his team are still learning how the brain talks.

“Just like a baby tries new sounds to find words, that’s what we’re doing with the language of the nervous system,” he says.

When Spetic took the prosthetic home for a short-term trial last October, Tyler and his team realized the need for the device to distinguish between textures.

The work now is creating a library of textures, by testing Spetic on what he feels when the prosthetic touches cotton or a ceramic tile. That information is then added to a catalog for future users.

Tyler cites other hurdles such as deciphering temperature or where the fingers are in space, but his connection to this project is as much emotional as it is scientific.

“When you see your kids, you give them a hug, or you hold your wife’s hand,” he says. “It’s all a sense of touch that brings a connection to the world.”

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5