As the Great Lakes Become a Data Center Hub, AI’s Water Usage Impact Remains Unknown

by Jaden Stambolia | Jun. 27, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Courtesy of NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, Courtesy Google Maps

Artificial Intelligence is becoming hard to avoid. ChatGPT is becoming more popular than Wikipedia. Google and Microsoft have built AI into their products. AI has even made its way into Cleveland classrooms and the Cleveland Clinic. We have even discussed how Cleveland Magazine plans to explore the capabilities of AI.

What is unknown to most is that a finite resource powers AI: clean water.

AI data centers consume massive amounts of water, both directly to cool their servers and indirectly for electricity generation.

A critical issue for the Great Lakes is that governments lack precise information on how much water these centers are already withdrawing from the lakes and what future withdrawals will be, as new centers emerge and technology continues to evolve. New York is the only Great Lakes state that has introduced legislation to address this issue.

"One of the big problems is that there are no water use reporting requirements for data centers when they're hooked into a municipal system that has the ability to supply them," says Helena Volzer, senior source water policy manager at Alliance for the Great Lakes, headquartered in Chicago.

The New York State Sustainable Data Centers Act, if passed, would require data centers to power their operations with 100% renewable energy by 2050 in the state, while also establishing reporting requirements for the amount of energy and water they consume.

According to Bloomberg, tech giants are racing to expand into new and larger data centers to support the growing popularity of AI. That expansion includes Lake Erie, where 11 million residents in the area compete with existing and planned data centers and other industries for that clean water.

"(The Great Lakes) think of ourselves as a water-rich place, but it really is kind of finite. It's a one-time gift from the glaciers that needs proper management," says Volzer. "Only 1% of it is replenished by rainfall, precipitation, snow melt and groundwater inflows."

It’s not just AI data centers. Other data centers that drive our digital world rely on water. In the Greater Cleveland area alone, there are about 20 data centers, two of which were recently converted from office spaces to data centers.

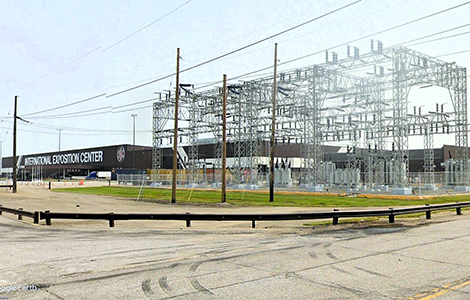

That includes the H5 Data Center, a 333,000-square-foot, Tier III data center at 1625 Rockwell Ave, and another is the Sterling Building at 1255 Euclid Ave. Even the I-X Center’s available 1.5 million square feet is reportedly being turned into a data center.

The presence of a 25-megawatt electrical substation on site is one of the reasons the I-X Center is reportedly being turned into a data center. Hyperscale data centers, which range from 100,000 square feet to several million square feet, can consume anywhere from 20 megawatts to more than 100 megawatts.

A megawatt is equal to one million watts. Watt is the rate at which energy is used and produced. For example, a 100-watt light bulb uses 100 watt-hours, whereas one megawatt could light two 60-watt light bulbs nonstop for a year or run two fridges for a whole year.

In 2021, the United States used 11,595 gallons of water per megawatt-hour for cooling power plants, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Sam Altman, co-founder and CEO of OpenAI, claimed in a recent blog post without providing evidence that each ChatGPT prompt a person enters uses 0.34 watt-hours, and what he describes as “roughly one-fifteenth of a teaspoon of water.”

Recent studies show different results. A 2023 study conducted by the University of California, Riverside, and The Washington Post found that using ChatGPT to write a 100-word email consumes more than 17 ounces of water.

That same study claims that if 1 out of 10 working Americans prompts that weekly for a year, it equals almost 436 million liters of water, which is essentially the amount of water consumed by all the households in Rhode Island in 1.5 days.

“AI can be energy-intensive and that’s why we are constantly working to improve efficiency,” Kayla Wood, an OpenAI spokesperson, told The Washington Post in 2024.

The amount of electricity and water used for each prompt depends on the location of the data center and can vary widely, according to researchers.

What makes the Great Lakes popular for data center development is the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact, which was formed in 2008. It protects that water from leaving the Great Lakes Basin.

“Nobody in the Great Lakes Council is going to tell you how to use your water, but if you want to take it outside the region, the compact kicks in," then Ohio State Rep. Matt Dolan said on the compact in 2008.

Since water can’t leave the basin, industries come here for it. In Northeast Ohio, clean water is used in steel and auto plants as a means to cool industrial equipment.

Historically, those industries also affected the Great Lakes’ groundwater. Now, AI data centers are doing the same. According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, approximately 42% of Ohio citizens rely on groundwater as a source for their drinking water and household use from both municipal and private wells.

“(Data centers’) biggest threat really is to groundwater that we can point to is where groundwater aquifers could really be impacted, based on the fact that when data centers use water, they evaporate it through evaporative cooling,” says Volzer. “That portion that's evaporated off when (data centers) pull from groundwater isn't returned to the watershed.”

While these data centers draw water from the Great Lakes, they also bring economic value to the state of Ohio, supporting around 85,000 jobs and generating approximately $10.5 billion in economic output in 2023.

Cuyahoga County Executive Chris Ronayne even said in 2023 that he expects to pitch the county as “a freshwater capital” and wants to attract even more businesses that use the water.

Volzer recommends that states localize water planning studies to better understand water demand and availability, as well as implement water use reporting for data centers.

“Nothing is the perfect solution. There's no free energy, there's no free anything. There's always going to be a trade-off. It's a matter of managing those trade-offs,” Volzer expressed on the domino effect that AI data centers bring. “And I think also being prepared for this new wave of economic development that (the Great Lakes) seems to be headed.”

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Jaden Stambolia

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5