Not Fade Away: The Grateful Dead's Cleveland Legacy Lives on Through Tapes and Memories

by Dillon Stewart | Aug. 1, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Melcher Oosterman, Illustration Zone, Anastasia Pantsios, Robbi Cohn

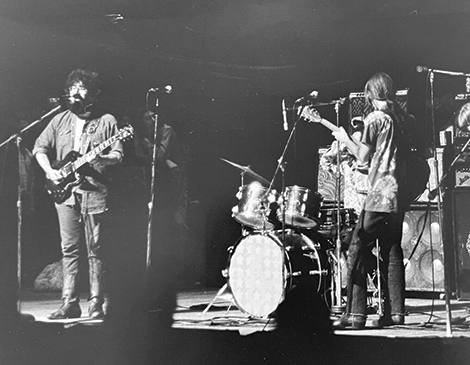

The Grateful Dead’s chaotic first appearance in Cleveland, at Cleveland Music Hall on Oct. 17, 1970, ended with a literal bang. But it started with four minutes of lazy noodling, sound checking and tuning. Rhythm guitarist Bob Weir picked at the “Star Spangled Banner,” while lead Jerry Garcia tagged “Me & My Uncle,” foreshadowing the setlist. “Good evening, football fans,” someone said, maybe referencing the next day’s Browns game against the Detroit Lions (a loss). The distant voice on the recording is unrecognizable, perhaps a roadie or bassist Phil Lesh or a “family member,” the freewheeling band’s hangers-on who were allowed to wander backstage and twirl on stage. Then, kicking off a 25-year relationship with Northeast Ohio, the band took off like a freight train with their biggest song to date, “Casey Jones.”

A 16-year-old Jeff Linton sat in the first row of the balcony that night with his 744T mono cassette recorder and a bundle of Nakamichi tapes. Today, Linton’s recording can be found on sites like archive.org and relisten.net along with almost every show the band ever played. It’s not for the Dead-curious. The tape warps and clicks. Shouts and claps from the crowd rise to the volume of the band. Lyrics are hard to hear. The bottom end is muddy. Linton and his friends murmur throughout the show, debating when to flip the tape or stop to preserve space. Songs fade out and return down the road, minutes of notes lost to history. During “Candyman,” you hear a fan mutter “I just snorted a gram of…” before trailing off.

In 2012, Linton, a decades-long Deadhead, realized the tapes were considered part of a “lost weekend” that included Philadelphia on the 16th and Minneapolis the next night. He emailed Dead historian David Gans, who quickly asked if he could digitize them. “I seem to recall seeing a review saying they were so loud that it could be heard in the Public Hall during a performance by either the Cleveland Pops or the Cleveland Orchestra,” Linton wrote. “What a BIG FAT SOUND they had back then! I’ve been on the bus ever since.”

Being a fan of the Grateful Dead in 2025 is as much about being a historian as it is about being a listener. Deadheads, as the fanbase is called, have recorded thousands of hours of shows in audio tapes and amateur videos. Experts estimate that about 2,200 of 2,350 of the band’s shows were recorded, whether from the soundboard or the crowd. They are one of, if not the, most recorded band in history. Lost recordings are as rare as they are coveted.

“Once or twice a year, these just pop seemingly out of nowhere,” says Jesse Jarnow, host of the Good Ol’ Grateful Deadcast. “It’s great because you get little pieces of stories that sometimes you didn’t know or stage banter. It adds to the bigger picture.”

Grateful Dead magic is strong in Cleveland. In more than 25 Northeast Ohio shows between 1970 and 1994, the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia Band developed love affairs with local venues such as Public Hall, Music Hall, Allen Theatre, Finney Chapel in Oberlin, Blossom Music Center and Richfield Coliseum.

“It took them a few years to come to Cleveland,” says Jarnow. “But [once they did], they really kept looping back. It was no small thing.”

The recordings range from grainy to studio quality, but even in the hard-to-listen moments, the band’s talent, chaos, community, heartache and excellence pour off the stages.

The tapes, paired with press clippings and fan memories, tell a story of a group that was in a state of evolution. They shed light on a band coming of age, experimenting, stumbling and growing. They show the story of America’s most recorded, most accomplished, most obsessed-over and, arguably, most important band.

If you want to know the story of the Grateful Dead, just listen to the music play. The tapes tell it all.

On this October 1970 night, Garcia stood in front of the Cleveland Music Hall crowd between amplifiers with tie-dyed grill cloths. “Turn the strobe lights down,” he told the back of the house. The first time he passed through Ohio in 1964, he was clean-cut with an acoustic guitar. Road tripping to find bluegrass records, he landed at a small tavern on North High Street in Columbus, where he sat in with the band Dixie Gentleman. When he returned four years later, a mop of black hair flowed around his round eyeglasses and into a thick beard, and he wore a denim button-up and a cherry red Gibson SG.

More importantly, he brought his new, electrified band, the Grateful Dead. The Dead first played Columbus, Cincinnati and a free concert at Ohio University in 1968. In April ’70, they returned to Cincinnati, this time growing from the Hyde Park Teen Center into the University of Cincinnati Fieldhouse.

Five years after its first show at a California pizza parlor, and three albums in, the band was established on the coasts but gaining traction in between. The ’70 tour supported its new psychedelic country record Workingman’s Dead, which was the first to get substantial airplay. Two weeks before the show in Cleveland, they’d sold out the 9,000-person Winterland in San Francisco.

But the band kept shooting itself in the foot. In 1969, they played the famous Woodstock Festival. Garcia called their set “terrible.” In December, the group helped organize the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, suggesting the Hell’s Angels as the security. The Angels ruled like the gang they were, punching a member of Jefferson Airplane and roughing up Dead roadies. A scuffle began as the

Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger wiggled to “Under My Thumb,” leading to a concertgoer being stabbed. The Dead never even went onstage. “Dark star rising,” as the song goes.

“How can you explain the Grateful Dead?” asked Plain Dealer rock critic Jane Scott in a profile of the band ahead of the show. A Cleveland crowd — half “Dead Freaks,” the pre-Deadhead moniker, and half newcomers and frat boys hollering for “Casey Jones” — remained cautiously curious of the Dead’s West Coast blend of psych-rock, country-

blues and jazz.

Scene reviewer Anastasia Pantsios was equally skeptical. “I must admit I am not a ‘Grateful Dead freak,’ a particular sort of human being whom, it is said, and I agree, is the only person who can fully appreciate this group, a group that plays for a particular sort of community and not for everyone,” she wrote. Pantsios found the Cleveland Music Hall a surprising venue for the hippies. The adjacent 10,000-seat Public Auditorium was fitting for a rock concert. Hendrix played there in ’68. But the adorned 2,800-seat Music Hall seemed designed for an opera.

“One expected ancient lorgnette-bearing dowagers swathed in mink to sail in on the arms of gentlemen in full evening attire,” Pantsios wrote. “It was an odd place for Cleveland’s first get-together with the notorious Grateful Dead.”

Yet, the Grateful Dead targeted these venues — and later missed, as it grew into a stadium act. “They took themselves seriously,” says Jarnow. “They didn’t want to be playing dingy rock clubs.”

As the band took the stage, the cards were stacked against them. The Dead were known to be sound-obsessed gearheads, later credited for pioneering much of the live sound technology used today. But in 1970, personnel challenges forced a tour on rented and house equipment. Throughout the show, Weir and Garcia asked for adjustments to the vocal monitors (the speakers that let them hear themselves singing, still a new invention). Some fans remember the vocals being difficult to hear, though they’re mostly legible in the recording.

Listening back, those challenges didn’t seem to matter. The band presented a setlist of tried-and-true tunes, including “China Cat Sunflower” into “I Know You Rider,” the country-tinged “Me & My Uncle” and the sunny “Sugar Magnolia.” “The Other One” wasn’t the jam it would become but still clocked in at 10 minutes. The second set stretched out a bit, a format that would become standard later. Pig Pen, who reportedly spent more time drinking beer than playing organ, rapped to “Good Lovin’.” The famous improvisational jazz-rock jam “Dark Star” from Live Dead, already becoming a rare treat for fans, devolved into screeches, feedback and long bending notes from Garcia before reemerging around the 17-minute mark for the first verse. The crowd grows more rambunctious as the night proceeds. Perhaps that mimicked the band’s antics and refusal to stop playing. Fans recalled the fire marshals standing on stage, telling the crowd to stop smoking. The house lights flicked on for the last quarter of the show, urging the band to wrap it up. The set ended with a rousing “Not Fade Away,” which transitioned into the first “Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad” to feature the “Bid You Farewell” outro. After an encore of “Uncle John’s Band,” Pig Pen shot a pink firecracker into the ceiling, nearly knocking Hart off his drum set.

“It ended most strangely,” Pantsios wrote. “It was a surrealistic finish to a wild night.”

The band soon returned. Leading up to ‘71 at the Allen Theatre show was a long, strange trip. A self-titled live album known as Skull & Roses, along with a Garcia solo record, helped the Dead’s star rise. Yet, the group missed both organist-singer Pig Pen, who battled alcohol-induced liver failure at 25 years old, and Hart, who stepped away after his father stole a huge sum of money from the group, altering its two-drummer attack. The Dead tapped virtuosic pianist Keith Godchaux to fill out the sound. In Cleveland, you can hear the origins of jam-band-leaning segues and sonic explorations, for which Godcheux provided a backbone. Thousands of fans tuned in to live radio broadcasts at home, including on Cleveland’s WMCR-FM, leading to some of the band’s bootlegged recordings.

In ’72 and ’73, the group toured relentlessly,

including a trip abroad that resulted in the album Europe ’72 and two performances at the 10,000-capacity Cleveland Public Hall. Equally legendary, both shows included the amorphous jazz rock tune “Dark Star.” The ’72 version became a fan favorite, but ’73’s was the longest song the Dead ever played at 43 minutes. But this period began a Civil War that existed pretty much throughout the band’s entire career: new fans vs. old fans and small shows vs. big ones. In some ways, it still does today.

“[The radio broadcasts] make even more fans,” says Jarnow. “That’s when shows start selling out and overcrowding.”

Snow fell on Oberlin College on March 13, 1976, as Garcia rolled in off a five-hour drive from a show in Evanston, Illinois. He zoomed past Deadheads hitchiking to the night’s show and shivering in line outside for a good spot in Finney Chapel.

The Dead did not accompany Garcia. Burned out by a relentless and chaotic four-year run from ’70 to ’74, the band went on hiatus. Yet, Garcia — a man known for playing guitar nearly every waking hour — soldiered on, as he did throughout his career. In all, he played an estimated 4,782 shows in his 33-year playing career. That’s one every two and a half days. Not to take from his love of the stage, many of these non-Dead shows funded the heroin habit that Garcia never fully kicked. From the green room, security guard Steve Silberman, the late New York Times bestselling author and Wired journalist and an Oberlin student, steered a stumbling Garcia away from a broom closet and toward the stage. It’s easy to imagine Garcia pushing his glasses up his nose and smiling at the two-story organ that backdropped the stage.

Jerry Garcia Band was among the first rock ’n’ roll bands to appear at Finney Chapel. Joan Baez played it in 1962 and Parliament-Funkadelic in 1970. Talking Heads later visited in ’77 and ’78. Built in 1908, the 1,200-seat church was perfectly cozy for the frigid spring night. JGB churned through Dead songs like “Friend of the Devil” as well as frequent covers, The Temptations’ “The Way You Do The Thing You Do” and the Stones’ “Moonlight Mile,” over an hour and a half. A decent recording exists, though some fans believe it is incomplete and might represent pieces of two shows the band played that night.

JGB returned to Ohio a few more times in the ’70s and ’80s. The Grateful Dead did, too.

Post-hiatus, the band played 41 shows in the second half of 1976, 60 in 1977 and 81 in 1978. They missed Cleveland in ’77 but returned in November 1978. As the roadies set up in the now-familiar Cleveland Music Hall, Weir felt off. Probably the cocaine, he might have thought. More than acid, the drug fueled the band at the time. The Oberlin crew rolled into town with heads full of Red Dragon blotter acid, courtesy of Silberman, amplifying what would become a wonderfully weird night. Weir sounded fine through the first set but didn’t return at the start of set two. Some fans said he was puking on the side of the stage. The Dead bought Weir time with about 15 minutes of freeform psychedelic madness, notes pouring from Garcia’s custom-built “Wolf” guitar. Eventually, he stumbled through “Jack-a-Roe” and Weir, sounding like he’s holding back gags, returned for one of his signature songs, “Playing in the Band.” Also memorable was “If I Had the World to Give,” one of only three times and the last time the band played that song live.

In 1984 and 1985, they graduated to the 23,000-capacity Blossom Music Center, double the size of Cleveland Public Hall. After the show, psychedelic explorers searched for their cars in Blossom’s vast parking lot. Like an acid trip you thought was over, the bigger venues welcomed a new wave of fans. One of those new fans at the 1985 show was Douglas Trattner, now dining editor for Cleveland Scene but then a recent high school graduate. Coming in blind, he’d spend the following years traveling to see the band at venues like Deer Creek, Buckeye Lake and Alpine Valley.

“It was the first time we’d taken mushrooms. We’re laying in the grass as it starts kicking in. The first song they play is ‘Day Tripper’ [by the Beatles]. It was like, I get it,” says Trattner. “It was the perfect bridge to adulthood. It became such an important aspect of our lives as friends in college.”

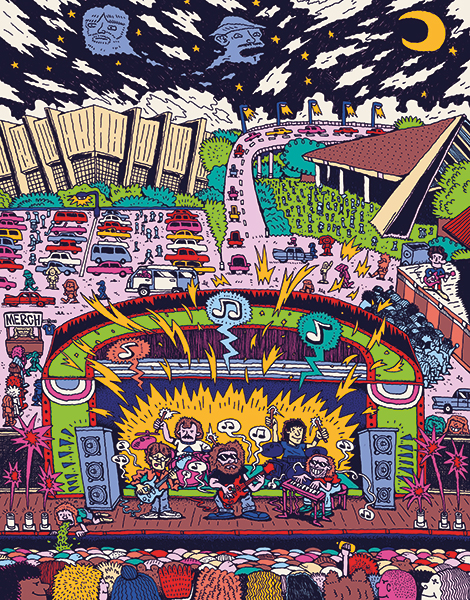

Across the 80 acres of parking lot at Richfield Coliseum in September 1990, bumper stickers on Ford Tauruses and Geo Metros, and a few remaining Volkswagen buses, declared their allegiance. “The Fat Man Rocks,” one read, a common reference to Garcia. “Who Are the GD and Why Do They Keep Following Me Around?” joked another. Many of the tie-dyed attendees who weren’t born with the Dead played Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests. In ’87, “Touch of Grey” gave the band its first (and only) MTV hit. The cult grew into a religion. One night in town wasn’t enough.

In 1990 and 1991, respectively, the band had the fourth-highest-grossing and top-grossing tours. The parking lot became an attraction. A joyous traveling bazaar, later called Shakedown Street, popped up in each city. Fans traded tapes, and vendors sold T-shirts, grilled cheeses and drugs.

Wandering fingers pointed to the sky looking for “miracles,” aka last-minute tickets. The lot scene got so wild that local authorities asked the band to record radio spots telling fans not to show up without a ticket.

“At the time, in Ohio, we weren’t really allowed to tailgate at shows,” says fan Marcus Dirk, who saw more than 20 shows between ’90 and ’95. “People would set up down the street at Dover Lake. It was insane.”

Despite the pinnacle of success, something was missing as the band kicked off its 1990 fall tour on Sept. 7 and 8 in Cleveland. Fans didn’t know what to expect from new keyboard player Vince Welnick, though they greeted him with signs reading “Welcome Vince!” and “Yo Vinnie!” Two months earlier, Brent Mydland became the third Grateful Dead keys player to die prematurely, at just 37 years old. Welnick, who played with The Tubes in the ’70s and ’80s, took the helm on keyboards. He had big shoes to fill. Mydland, who served for 11 years, the band’s longest tenured keyboardist, was a fan favorite. Welnick proved to be yet another divisive selection for Grateful Dead fans, some of whom found his electronic tones grating. These shows in Cleveland, captured this time on an amateur video, were his first after cramming the catalogue of more than 150 originals and many more covers. After a run of longtime favorites including “Ramble on Rose,” “Me & My Uncle” and “Althea,” Garcia did what he almost never did in 35 years: He addressed the crowd. The spiritual leader of the band stepped to the microphone, looking relatively healthy and stately to give his simple stamp of approval: “I’d like you all to meet Vince Welnick playing keyboards.”

The addition of Welnick wasn’t the only first that night in 1990. The Sept. 7 concert began a 13-show love affair with Richfield Coliseum that would last through the band’s final Northeast Ohio show in 1994.

When the Grateful Dead visited Richfield in 1994, Garcia, just 51 years old, looked like many of the darker characters he sung about: beaten down and staring death in the face. His curly, black-gray hair was greasy and white. His face was weathered, and he was heavier than in 1990. Following a 1986 collapse and diabetic coma, Garcia spent the next few years sober and scuba diving for exercise. Around the overdose death of Brent Mydland, he spiraled back into an addiction to smoking heroin that lasted the rest of his life. Throughout the mid-’90s, his struggles were evident. Some fans remember sloppy play. An influx of dirges filled the setlist.

“You could see the toll it was taking on Jerry,” says Dirk. “Something turned dark about the scene. The flood of heroin, everyone really strung out. People ODing here and there.”

Art again imitating life, there were bright spots amidst the darkness. That March weekend in Richfield showed a cogent Garcia (albeit stationary with eyes locked on his guitar), singing strongly in the upbeat “Bertha,” fluttering through solos on “Tennessee Jed” and briefly smiling at Weir, his longtime right hand, during a cheery cover of “I Fought the Law,” a song debuted at Richfield in 1993.

Earlier that year, the Grateful Dead arrived at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City for the ninth-annual Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, looking out of place in tuxedos. They were to be inducted into a class that included Bob Marley, Rod Stewart, The Band, The Animals and John Lennon. Garcia was noticeably absent. Well, other than the cardboard cutout the band brought along. The joke proved bittersweet, foreshadowing the post-Garcia era. On Aug. 9, 1995, Garcia died of a heart attack at a California addiction center. The nurse who found him said he was smiling.

The Dead were due to play three nights at the brand-new Gund Arena in October 1995. Less than five years later, a wrecking ball smashed Richfield Coliseum to pieces. It’s now a green patch of Cuyahoga Valley National Park popular with birders.

Similarly, the Grateful Dead’s music continues to flourish. The band never again played as the Grateful Dead, but members splintered into side projects dedicated to playing their songs. Over the last decade, the music saw another surprising renaissance. In 2015, Weir, Hart and drummer Bill Kreutzmann enlisted pop-blues guitarist John Mayer to form Dead & Co. The tribute visited Blossom Music Center in 2017, 2018 and 2021. Its final tour in 2023 drew more than 840,000 fans and subsequent residencies at the high-tech Sphere. This month, the group takes over Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, the site of their famous free shows of the ’60s, for a three-day festival, joined by Phish’s Trey Anastasio, Sturgill Simpson and Billy Strings, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the group. While many old Heads deride Dead & Co. as a subpar cover band and Mayer as a poser, younger fans relish the opportunity to see the band’s surviving members in whatever capacity they can. For amicable, seasoned Heads, like Kristin Parrino, it’s a flashback.

“You don’t want the music to die,” says Parrino, who has tickets to San Fransisco. “Dead & Co. has inspired a new generation of fans to reinvest in this great music.”

Over 35 years, the group soundtracked the psychedelic revolution, pioneered live music and brought the spirit of freedom to American cities like Cleveland. Whether in tribute bands, or in their parking lot tailgates, or in the merch by just about every major retailer (including Homage honoring Ohio’s shows), or in the dusted-off recordings, The Grateful Dead’s lives on as the Great American Band. At least once a month, you can find a Grateful Dead cover band playing somewhere in Northeast Ohio. Like Mozart or the jazz greats, the songs have been reinterpreted, inspired by the band’s fondness for reinvention.

“What I’m hoping is to be able to see some way of extending this idea beyond ourselves,” Garcia said in a 1988 interview. “I’d rather this idea continue without us. It doesn’t have to be the Grateful Dead, but it has to be something.”

It’s anyone’s guess, but likely he would have appreciated that — in Cleveland and beyond — the music never stopped. And even if it does, we can always run back the tapes.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Dillon Stewart

Dillon Stewart is the editor of Cleveland Magazine. He studied web and magazine writing at Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism and got his start as a Cleveland Magazine intern. His mission is to bring the storytelling, voice, beauty and quality of legacy print magazines into the digital age. He's always hungry for a great story about life in Northeast Ohio and beyond.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5