Commentary: Brook Park Browns Should Become Reality

by Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans | Aug. 7, 2024 | 7:20 PM

Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans

The following article was published as part of an exclusive content partnership with neo-trans.blog.

In the coming weeks, the owners of the Cleveland Browns will reveal their plans to build a $3.6 billion domed stadium and associated development in the Cleveland suburb of Brook Park. According to public sector sources familiar with the plans, owners Jimmy and Dee Haslam have their capital funding identified for the stadium and a small first phase of development.

Cost of the new domed stadium and the provision of about 20,000 parking spaces, almost entirely in surface lots, is estimated at $2.2 billion. Half of that will be privately funded and create new tax revenues that will fund the other half. Much of the funding for the stadium will come from bonds serviced by new stadium-related revenues and city, county and state taxes generated by stadium activities and employment. Another $1.4 billion in private, stadium-area development is planned.

The Haslams have reportedly identified their bond financing firm, a company with lots of experience in financing sports stadiums, arenas and entertainment venues. And they have hired their joint-venture construction management team for the Brook Park site — M.A. Mortenson Co. of Minneapolis and Independence Construction of Independence, soon to be relocated to Brecksville.

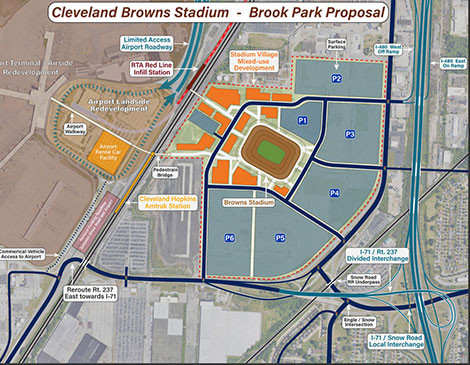

The Haslams have a purchase agreement to acquire 176 acres of land at 18300 Snow Rd., site of two former Ford auto plants. NEOtrans broke the story in February about the purchase agreement and was first to publish a rendering of the proposed domed stadium. We also reported two years ago that the Haslams wanted a new stadium for the Browns. Why do they want one?

Rebuilding Cleveland Browns Stadium on Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront has too many downsides. The most significant is the condition of the stadium itself which is deteriorating rapidly and, short of tearing it down and starting over, would not have produced a long-term stadium solution. Sources told NEOtrans the city’s desired 30-year lease with the team would have outlived a renovated stadium.

Last week, Mayor Justin Bibb publicly released the city’s $461 million offer to help finance a $1 billion renovation of the city-owned Cleveland Browns Stadium. Bibb urged the Browns to respond by Aug. 12. That’s not a coincidence. City officials heard that the Haslams are likely to make an announcement as early as that regarding a new domed stadium in Brook Park.

Bibb published his offer to the Haslams as political cover to demonstrate that the city has done all it could to keep the Browns playing in the city of Cleveland. But it’s not enough. The city can file a lawsuit under the Modell Law, as Scene Magazine notes. But I don’t think it will. Cleveland is still going to get lots of benefits from a stadium located only 1,000 feet outside of the city limits, next to Cleveland Hopkins International Airport that’s about to get a $3 billion makeover.

Dave Jenkins, chief operating officer at the Haslam Sports Group, said the Haslams seek “a long-term stadium solution that creates a world-class experience for our fans and positively impacts Northeast Ohio.”

Further structural reconstruction work would have been too expensive and resulted in the city having to dip into general revenue funds that would affect city services. That includes using income tax revenues from stadium-related employment which is an already existing revenue stream to the city.

But that’s not the case in Brook Park where all stadium-related tax revenues would be new to the suburb and could be directed to retire stadium construction bonds without affecting city services. The smaller size of Brook Park isn’t the compelling factor as it offers many of the same legal tools like tax-increment financing (TIF) and tax abatement as larger Cleveland.

Look for the stadium building to receive tax abatement or to be owned by a tax-exempt entity, saving the Haslams tens of millions of dollars per year. That means only the land might generate property taxes. But by being improved and newly occupied, the land value will increase and generate millions more in property taxes or payments in lieu of taxes for Brook Park schools than it does now.

While Brook Park doesn’t have the debt capacity that Cleveland does, bonds aren’t always issued by cities. The cities create the TIF districts and mechanisms, then sign agreements with the local port authority to issue the bonds. Those are steps which will be taken this fall and into next year. One of the biggest bond issuances will be done so privately, as few revenue streams will be as prolific to supporting stadium construction as parking revenues.

The city of Cleveland tried to compete with Brook Park by offering up all of the revenues from the combined 3,700 parking spaces among its Willard Park Garage and the North Coast Municipal Parking Lot on stadium event days. Over 30 years, event parking at those facilities was projected to generate $94 million toward renovating the 1999-built stadium.

That pales compared to more $500 million in parking revenues the Browns could generate over 30 years at Brook Park, where 20,000 parking spaces are planned for the 60,000-plus-seat stadium. That parking-to-seating ratio is common among National Football League (NFL) stadiums that are not downtown.

The $500 million in parking revenue over 30 years is based merely on a limited number of events, like what Cleveland Browns Stadium has been able to host. The 20,000 surface parking spaces would require nearly 140 acres of land. A Red Line rapid transit station at the west end of the Brook Park site could handle another 5,000 stadium visitors.

Another 15-20 acres will be for the stadium itself and plazas outside of it for staging crowds. That leaves 15-20 acres for future development. Patriot Place at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, MA, for example, measures 18 acres. In the interim, a portion of the land of outside the Brook Park stadium will be used for parking lots but could be developed with parking garages to open up land for more hotels, restaurants, shops, health care facilities and multi-family housing.

The parking revenue estimates don’t take into account all of the indoor events a new domed stadium and Destination Cleveland could attract — National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football playoffs, NCAA bowl games, NCAA Men’s Final Four basketball games, gymnastics competitions, more concerts and a Super Bowl.

Additional funding to service bonds for the domed stadium’s construction would come from admissions taxes on large events. Currently in Brook Park, that tax rate is set at 3 percent but could be raised to 8 percent to equal that of Cleveland’s. If it is, the admissions tax from stadium events would generate $227 million over 30 years.

The Haslams are also seeking up to $600 million in state funds with bipartisan support coming from Republican Gov. Mike DeWine, Republican Rep. Tom Patton of Strongsville and Democrat Rep. Terrance Upchurch of Cleveland. A mix of state bonds, capital grants for infrastructure and other tools appear to be in the offing.

The NFL is also likely to put money into this new stadium. The league has loaned anywhere from tens of millions to as much as $500 million for new stadiums. The NFL has been most generous where one facility is shared by two teams, in the New York and Los Angeles metro areas. A loan for the Brook Park stadium may be at $100 million or less. There will also be lucrative naming rights to the stadium, its gates, and other locations around the property.

Cuyahoga County’s support can include $120 million over 30 years from the sin tax on alcohol and tobacco product sales. The city of Cleveland has a $20 million reserve in sin tax funds but it may tap that to demolish Cleveland Browns Stadium after the team’s lease ends following the 2028 season. It cost $20 million to demolish RFK Stadium near Washington DC in 2020.

Demolishing a publicly financed stadium that’s less than 30 years old isn’t something any taxpayer would want to see. It cost $283 million to build in 1999, or $550 million if built today. It received a $120 million cosmetic renovation in 2014-15 and looked amazing afterwards. But that didn’t address the structure so it didn’t last. Two years ago, Cleveland Browns Stadium needed $10 million worth of emergency repairs and it needs another $3.7 million in emergency repairs now.

The stadium is falling apart because it was built quickly and poorly, and because it is an amenity-laden outdoor facility in an inhospitable environment. It is blasted by icy, moisture-laden winds coming unimpeded off a Great Lake.

The only the thing another major stadium renovation would do is buy some time to find a new long-term solution. That could involve creating a site in Cleveland for a new stadium and supportive development. The current stadium, even if renovated for $1 billion, has 15-20 years left, multiple sources say.

If true, think about what that means. The city would gain 15-20 years to create a site while we, the taxpayers, are paying off half of that $1 billion worth of near-term renovations to the existing facility. We would still be paying for those renovations for 10-15 years after the current stadium is demolished and while we’re starting to pay billions for a new stadium that replaces it.

If Cleveland officials want to keep the Browns playing in the city proper, they’re going to need a 1981 DeLorean with the flux capacitor upgrade package to do one of two things.

One option is to go back to 1996 when the city won the chance to get the Browns back after Art Modell took his football team to Baltimore the year before. Mayor Mike White was unwilling to wait for a well-thought-out site for a solidly built stadium. Instead, White wanted the Browns playing in Cleveland again before the 1990s ended. That meant building a new facility quickly on the old stadium’s foundations and using its water and sewer infrastructure.

The other option is to go back to the 2014-15 renovation. Then, the Haslams and Mayor Frank Jackson could have told us that the renovation didn’t fix what ails the stadium. But it give us a decade or so to find or create the ideal stadium site in or near downtown Cleveland. Several options were recently considered but there wasn’t enough time to make them development-ready before the stadium lease runs out after the 2028 football season. There is the school of thought that football stadiums, because of their limited number of events but huge parking requirements for those events, don’t belong downtown anyway. It’s why half of all NFL teams don’t play in downtown stadiums. In Cleveland, thousands of parking spaces are to be lost to the city’s lakefront redevelopment some of which is already underway. They include an expanded Rock-n-Roll Hall of Fame and improved public spaces around the Great Lakes Science Center. Together, those two attractions generate 50 percent more attendance than Cleveland Browns Stadium yet require less space and much less parking. In the end, Downtown Cleveland will do better without the Browns playing there. Brook Park will do better with the Browns and other high-profile events being hosted there. And the Haslams will do better by having a domed stadium there, near their expanding Berea headquarters, and surrounded by parking from which they will get the revenue.

I realize that big changes make some people uncomfortable. But this is a change that makes sense for just about everyone concerned. As for the Greater Clevelanders who might be inconvenienced the most by this change, I just have one suggestion — leave a bit earlier for the airport on stadium event days.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans

Ken Prendergast is a local professional journalist who loves and cares about Cleveland, its history and its development. He has worked as a journalist for more than three decades for publications such as NEOtrans, Sun Newspapers, Ohio Passenger Rail News, Passenger Transport, and others. He also provided consulting services to transportation agencies, real estate firms, port authorities and nonprofit organizations. He runs NEOtrans Blog covers the Greater Cleveland region’s economic, development, real estate, construction and transportation news since 2011. His content is published on Cleveland Magazine as part of an exclusive sharing agreement.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5