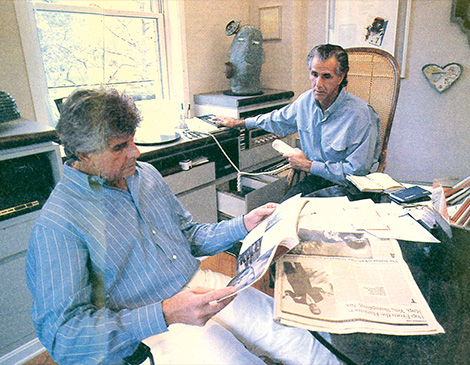

Jules and the late Myron “Mike” Belkin almost lowered the curtain on Belkin Productions before it really began.

The brothers — young men working in their parents’ Belkin’s Men’s Shop at West 25th Street and Clark Avenue — had presented two shows by The New Christy Minstrels and The Four Freshmen at Music Hall one February 1966 night on a lark. It was undertaken based on the experience Mike had gained booking bands into an Ashtabula ballroom for promotional events staged by the landlord of a discount store they’d opened in town. They thought they made $57. (A review of records years later revealed they actually lost $250.) A subsequent booking of The Mamas & The Papas resulted first in drug-induced postponement, then cancellation.

“We said, ‘We’re out of the business. We just don’t want to do this. It’s not too stable,” Jules remembers.

Then Mike received a call from a program director at WJW-AM. Respected jazz concert promoter George Wein, he relayed, was looking for a local partner to produce a festival.

“We’re thinking, with a guy like that, with that kind of reputation and success, this might be a place to take another shot,” Jules says.

The August 1966 show at the now-defunct Cleveland Arena, which featured the likes of Miles Davis and Sarah Vaughan, was a financial success, one that put the brothers on the road to becoming regional concert promoters who, along with rock powerhouse WMMS-FM, helped put Cleveland on the map as a tour stop for every baby band and major act in the genre. Jules attributes the company’s success to a constant quest for opportunities and sheer timing — he and Mike established Belkin Productions when popular-music acts were booked primarily by bar and club owners to play in their establishments. Bona fide promoters simply didn’t exist in most markets.

“We got into the business when it was no-rules, nothing to fashion what we were doing after,” he says. “We created the whole business from the ground up.”

By 1972, the Belkins had closed the discount store, their parents had sold the men’s store and the brothers progressed to booking a series of summer shows at the Akron Rubber Bowl. The concerts were headlined by everyone from the Osmond Brothers to Black Sabbath to the Rolling Stones, the last of which drew a sellout crowd of approximately 32,000.

“It was really, probably, the first outdoor series of concerts in the country in a confined area,” Jules says.

The following year, they brought Leon Russell to Cleveland Municipal Stadium. While seating was limited to 20,000, mostly in the bleachers, the show paved the way for the World Series of Rock by going off without incident. The first, on June 23, 1974, put the Beach Boys, future Eagle Joe Walsh and his then-band Barnstorm, Lynyrd Skynyrd and REO Speedwagon on the field stage for a full day of music that Jules estimates drew 40,000 people. The company went on to book 14 more general-admission “games” over the next six years while presenting concerts at venues all over town.

After a tragic incident that took place outside of the stadium of an Aerosmith-headlined World Series of Rock in 1979, Jules says, “The tenor of concerts just generally, throughout the country, became more sophisticated.”

At the same time, Mike was managing a growing roster of local, regional and national acts. The first, according to Jules, was The James Gang, perhaps as early as 1969, after Mike became friendly with the band’s drummer, Jimmy Fox. Mike’s son Michael, a president in the Great Lakes Region of Live Nation Worldwide who began working summers at Belkin Productions as a teenager, rattles off additional clients including the Sir Douglas Quintet, The Staple Singers, Mason Ruffner, Michael Stanley Band and Donnie Iris and the Cruisers.

“He loved the creative process — ultimately, that’s what drew him to managing artists,” Michael says.

Keyboardist, songwriter and producer of Donnie Iris and the Cruisers, Mark Avsec, who was also a member of Wild Cherry and Breathless, remembers that during the late 1970s, Mike advanced each member of Breathless a weekly stipend so they could rehearse rather than wait tables to pay their bills. “It turned out to be a good investment for Mike because, eventually, Breathless got signed by EMI America Records,” the now-copyright, trademark and media lawyer at Benesch, Friedlander, Coplan & Aronoff in Cleveland says. Iris adds that Mike, along with business partners Carl and Chris Maduri, formed a record label, Midwest Records, just so the then-unsigned Donnie Iris and the Cruisers could get their first album, “Back on the Streets,” into record stores and radio program directors’ hands.

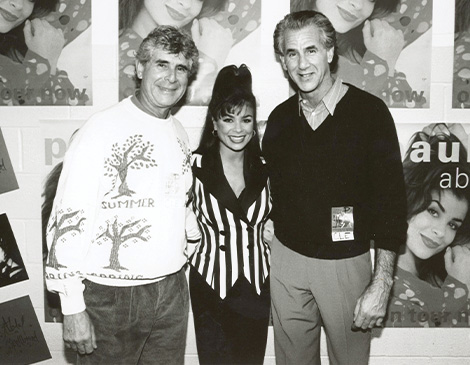

“[Mike] just did everything for us that he could,” Iris says. “It’s tough to explain, but when we were in his presence, the entire group just felt better.”

The strong relationships the Belkins developed with artists and their management teams by making sure crews were comfortable, hosting post-concert parties, etc., along with their expertise in presenting stadium shows, allowed them to expand into the “feudal kingdoms” of other promoters all over the Midwest, according to longtime Belkin employee Barry Gabel, now Live Nation senior vice president of marketing and sponsorship. “We would go wherever the band would want us to go,” he says. Jules remembers taking Pink Floyd and Genesis to stadiums in cities such as Detroit, Indianapolis and Columbus as well as Cleveland in 1987 and the Trans-Siberian Orchestra (TSO) to the Palace Theater and four other venues across the country in 1999 — the first dates for a band whose performances have become a holiday tradition for many. Gabel says the company did 14 TSO shows in 2000 and 21 in 2001, in cities as far away as Portland, Oregon.

In the early 1990s they partnered with Indianapolis promoter Dave Lucas of Sunshine Promotions to build Polaris Amphitheater in Columbus. The brothers already had the Odeon, a club in Cleveland’s Flats, where Mike was presenting emerging talent. “Columbus was a good city, but it didn’t have any venues — it didn’t have any arenas,” Jules explains. “The biggest place they had was a 4,000-seat Veterans Memorial [Auditorium].”

The Belkins also began producing events other than concerts, such as the Moscow Circus, Motorcycles on Ice, Tough Man Boxing and the Broadway hit “La Cage aux Folles.” (They appeared in drag at a 1985 Music Hall press conference to generate buzz.) In the early 1990s, the company received a call from then-Cleveland mayor Mike White. That conversation yielded the Great American Rib Cook-Off (the longest-running of the Belkin-produced festivals at 24 years), KidsFest, Pepsi Country Music Festival, Taste of Cleveland and Midwest BrewFest.

“Mike and Jules … always felt like the team that they had assembled was able to sell anything, was able to understand the product,” Gabel observes.

Both Belkins donated their time, talents and financial resources to various nonprofits in the Cleveland arts community. They were instrumental in bringing the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, then the inductions, to the city, according to Rock Hall president and CEO Greg Harris.

“For the music businesspeople that were looking for a home for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, it was incredibly meaningful that somebody they’d been doing business with for decades and was very successful was advocating for Cleveland,” he says.

Jules still serves on the Rock Hall board of trustees as well as the advisory committee of the Tri-C JazzFest and the board of directors of the Cleveland International Film Festival, an organization he once led as president. As a trustee emeritus of the Jewish Federation of Cleveland, he sits on the development and security committees, the latter of which he once chaired. He and wife Fran also are supporters of the fledgling BorderLight Festival.

According to Mike’s wife Annie, Mike was an avid collector of contemporary glass who gave works from his collection to various museums — he donated funds to build a wing at the Akron Museum of Art to house his gift of 80-plus pieces by artist Paul Stankard. They were longtime supporters of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, where they helped raise funds to build a new gorilla habitat.

Jules and Mike sold Belkin Productions to Clear Channel Communications in 2001. (Clear Channel Communications spun off as Live Nation in 2005.) Jules notes that a lot of independent promoters around the country were selling out, and he was thinking about retiring. “The business was changing — it’s no longer a mom-and-pop type of industry,” Michael observes. “Big dollars, high risk.” Mike continued his involvement in special events such as the rib cook-off and maintained working relationships with Michael Stanley and Donnie Iris.

“He never wanted to retire; he viewed it as the equivalent of quitting,” Michael says of his father, who died in 2019.

Jules didn’t completely realize the importance of the company they’d built, or how much the shows they brought to town meant to the people who attended them, until he was no longer working. He always was backstage “settling shows, taking care of business.”

“Once I retired and had the opportunity to sit out in the audience and feel that vibrancy, feel that excitement, I kind of appreciated then what we were doing,” he says. “It never occurred to us that there was that kind of feeling out there.”