How Cleveland's Schools Have Modernized STEM Education Through the Years

by Kristen Hampshire | Aug. 12, 2024 | 9:00 AM

Ken Blaze, Courtesy Laurel School

How do you define STEM without the S, T, E and M — taking science, technology, engineering and math out of the equation entirely?

The question is a stumper.

But Kate O’Hara likes to pass out Post-its for scribbling ideas to the rooms of teachers she consults with as coordinator for the Ohio STEM Learning Network Northeast Ohio hub.

Words like collaboration, rigor, planning, problem-solving and thinking outside the box fill those notes. “They come up with all these characteristics of STEM, and then I’ll say, ‘Isn’t that what good teaching and learning is?’” relates O’Hara, also an assistant professor of research for STEM Education at Cleveland State University.

When STEM emerged as an acronym and initiative in 2009, the number of graduates in these fields dwindled. “We needed more people to graduate with STEM-related degrees, but that is not how STEM has evolved,” O’Hara says.

Basically, STEM is an interdisciplinary approach to life, and there’s a real hard-knock aspect to it that instills grit.

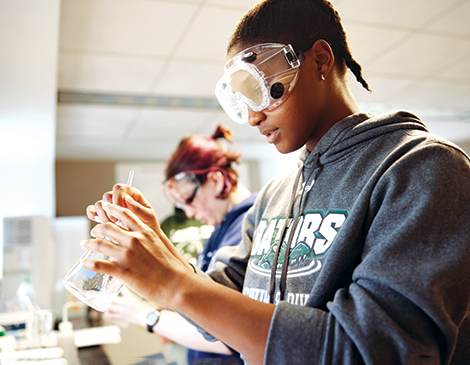

“In our Google world, we want immediate answers, so part of STEM learning is pushing yourself to move through authentic problem-solving,” says Kim Corrigan, a Laurel Upper School science teacher who works with students on research projects.

Rather than asking “Alexa, what’s the notification?” and getting an instant response, inquiry- and project-based learning promotes an old-school skill of figuring it out with newfound tools.

With try-fail-overcome experiences come valuable soft skills and character development, which the Belding family has witnessed with their children, particularly Eve, a rising senior at Laurel School.

She and a few close friends started The Science Sisters and launched the school’s first LEGO League team that went to state finals in year one. Now, Eve is on a project at Case Western Reserve University’s Sears think[box] helping conduct research.

“She was in the lab chatting up a bunch of Ph.D.s — I couldn’t even imagine this a year ago,” says her father, Jonathan Belding, an orthopedic spine surgery specialist at MetroHealth.

Eve’s charge, in overly simplistic terms: to slow down a robot that’s going too fast. “Her growth has been tremendous — the ability to ask questions and feel comfortable getting information from people who are a lot more senior than her,” Belding says.

He likens it to watching medical residents evolve their patient communications. “Initially, they have the technical skills,” he relates. “Then, they become more comfortable translating those to a layperson.”

He adds, “A majority of [STEM] isn’t necessarily math or building the robots. With these projects, they work together, they create a pitch and present to judges.”

STEM bucks the notion that every player gets a trophy, in a healthy way, and the learning starts on day one and never stops.

The early years

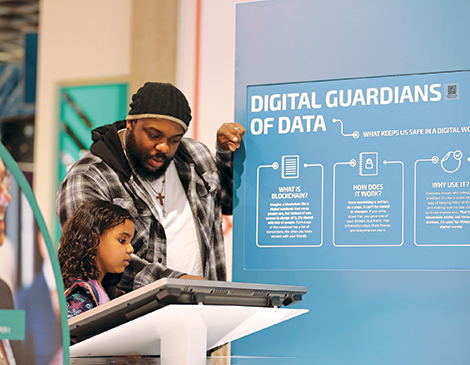

“Children are born curious,” says Kirsten Ellenbogen, president and CEO of Great Lakes Science Center. “They’re scientists in the crib, and the more we appreciate what young children are doing as they are learning, the easier it is to help them stay curious.”

Take a typical scenario: A tiny one pushes a bowl off the highchair tray and watches while it plops to the ground — again and again and again.

It’s cause and effect.

“As parents, we have trouble being patient through that, but it’s an experiment: learning, interacting with the world, testing,” Ellenbogen relates. “And they don’t get it the first time. Repetition at a young age is a key part of learning.”

A mindset shift from “this is frustrating” to “this is learning” goes a long way. “It’s not always easy,” Ellenbogen says. “But it can help us see our children in a different light.”

She adds, “It’s important that children value learning as an adventure, an opportunity — something they are excited to do.”

Early experiences playing in the backyard, visiting parks and discovering interesting places provide fodder for encouraging STEM thinking. “Part of what science centers and museums do best is help people develop interests,” Ellenbogen says.

“You don’t have to know STEM to have a conversation about it,” she points out.

Just ask, how do you think it works?

Grade school STEM

“In grades K to 8, it’s all about integration and exploration,” says Mindy Byrnes, a second-grade teacher at Laurel’s Primary School.

Technology is so seamlessly integrated across subjects and projects that it becomes second nature. But it’s not really about the tech. For instance, by the time students complete second grade, they know their way around the Seesaw learning management system. “They can take pictures of documents they create and post them in a journal,” Byrnes says.

The tech is a tool to gain more complex growth-mindset skills, such as realizing progress from hard work. “They record themselves reading a passage on Seesaw at the beginning and end of the year, and they can compare how far they’ve come,” Byrnes says.

Thematic learning is an emphasis — connecting areas of study like social studies and science or language arts and math with collaborative projects. Those launch with a universal question.

For instance, second graders are studying the effects of where we live on how we live. “We do that with a study of natural resources and compare different regions and how people of the past used those to survive,” Byrnes explains.

An overarching “investigate the world around you” aspect to these projects establishes a local-global connection, which is every bit a STEM concept as coding.

In primary school, this includes a Power and Purpose program that integrates engineering, math, language arts and community service. Fourth graders have built bridges, benches and even a dock extending into a pond on the Butler Campus. The best part: a tangible product that transforms their learning environment and instills a feeling of, “I did it.”

A study of water as a natural resource tied to the Great Lakes kicked off with a trip to the school’s entrance, close to Byrnes' classroom. There, the students review the mission statement: to inspire each girl to fulfill her promise and better the world. “I emphasize this piece of bettering the world,” she says. “Then, we bring it full-circle during our project to ask, ‘How can I make a difference?’”

As O’Hara noted, there’s nothing straight-up science, tech, engineering and math about today’s STEM. It’s integrated, inspired teaching and learning — making vital connections.

Next, the class visited the Lake Erie shoreline to partner with the Alliance for the Great Lakes, collecting water quality and beach condition data. They picked up trash — and, yes, analyzed it. What type of stuff are people tossing into the watershed?

Students dispatched data to the alliance.

Project-based learning through the years gives kids access points to STEM concepts, so the learner who says, “meh,” to math might discover an interest in an artistic aspect of a study.

Corrigan notes how a higher-level engineering course requires technical drawing. “That connects the artists to STEM,” she says.

Ellenbogen adds, “There is an important intersection between STEM fields and the humanities, and the skills of the future cross those — creativity, working through an idea from conceptualization to implementation. The ability to change what you’ve created applies whether you are engineering a solution or writing and editing a story.”

RELATED: How a New Approach Is Helping Cleveland Students Find a Passion for STEM Education

Workforce readiness

Expanding community and global connections through STEM and project-

based learning leads to career exploration and hands-on experiences. Eve’s growth as an inquisitive learner landed her at think[box].

There are many pathways.

Career tech education is the ultimate hands-on, problem-solving learning with real-world application, and it’s highly accessible. “For the longest time, career tech was thought of as ‘manual labor’ and for kids who aren’t going to college, but that’s not at all the case,” says Yakoob Badat, coordinator for West Shore Career-Technical District.

West Shore is one of a half-dozen career planning districts in Cuyahoga County, including Heights Career Tech and Cuyahoga Valley Career Center. Badat says, “Creativity and innovation are skills that career tech allows you to practice in a hands-on way.”

At West Shore, students in their junior year can choose to enroll in 13 programs with two more coming online — welding and microelectronic mechanical systems (MEMs). Students experiment across engineering and tech fields, including nursing, information technology, theater arts, media art and design and electronic engineering technology.

“Students work in diverse groups and navigate problems, practice perseverance and use critical thinking, which are all important skills in any career pathway,” Badat says.

Career tech programs put classroom concepts into action.

And students can gain industry credentials to move right into the workforce, earn college credits to transfer to a two- or four-year degree and, importantly, test-drive areas of study with less risk.

“I’d rather students try something for two years and gain a skillset and realize, ‘This isn’t for me,’ than spending those years in college and backtracking,” Badat says.

Students interested in a range of STEM fields can also beef up a college application with this type of hands-on experience.

Corrigan restates the benefit of flexing your risk factor in high school. “STEM learning gives students the tools they need as they move to the next level, and they can take risks in a comfortable environment and explore,” she says.

This is also a time to pursue interest-driven projects.

A Laurel capstone program allows students to deep-dive into areas of interest. And continued hands-on learning with projects such as building a cardboard chair that will support Corrigan’s weight, then voting on the winning protocol and passing it on to a fictional engineering client, carries perseverance lessons — important at all ages, including adulthood.

The key for parents, O’Hara says, is to “trust the process” and recognize that kids today require different skills. She tosses out this curveball: Do we need to memorize every U.S. state's capital city when tools are in place to provide those answers?

Maybe we need to ask tougher questions.

“School is not what it used to be,” O’Hara says, relating that some parents can push back because it’s new territory. That’s a good thing, because life is different now and, “Learning is different now.”

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5