A Cleveland Author’s New Book Maps Out the Geographic History of Northeast Ohio

by Jon Wlasiuk | Apr. 11, 2025 | 4:32 PM

Libby Geboy, Derrick Turner

Hambden Orchard Wildlife Area is a good place to look for a beginning to the story of Northeast Ohio.

Located about 30 miles east of Downtown Cleveland, the wildlife area lacks just about every amenity you might expect at a national, state, or local park. There are no interpretive signs, benches, or even marked trails here. Aside from a rough circle of gravel and a single wooden sign with the name of the location, you are on your own to push your way through 842 acres of second-growth hardwood forest sprinkled with stands of pine and invasive honeysuckle.

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Wildlife has managed this site since the 1950s, when the state purchased the land with the aim of surrendering a few acres of apple trees to habitat for wildlife. Aside from a scattering of spindly crab apples, the nonhuman world has fully reclaimed this area, a reminder that the land beneath our feet is a living force guided by a natural order that we did not create and have often failed to understand.

When I visited the wildlife area in late November 2022, a storm was kicking up over Lake Erie. Steel-colored clouds crowded out the sun, and locals were making a last-minute rush for groceries and gasoline. This is the heart of the snow belt in Ohio, and residents take the weather seriously. Northern Geauga County regularly records snowfall in excess of 100 inches per year. The lake effect snow, combined with sandstone ridges reaching 1,300 feet above sea level, are enough to offer even modest skiing. It will never compete with Aspen, but it’s enough to keep a few ski lifts churning during the winter.

The interplay between the lake and the Allegheny Plateau east of Cleveland is also responsible for something else I was looking for. As I made my way from the gravel parking lot and into a thicket of chokeberry brush, my feet carefully navigated icy mud. Each step I took created a crunch-squish that was strangely delightful, as though I was walking on a field of crème brûlée. Around a bend, I met a teenage girl in hunter orange—her bright, acrylic nails gripping her shotgun — who greeted me with a nod. I asked her if my passing to the east would spoil her chances at a deer, but she waved me by and laughed, telling me her fellow hunters were posted up in the other direction and I was fine to go on my way.

This landscape is mostly forest, but make no mistake, this is also a wetland environment. Although the official site is just a few miles to the east in a ditch off Clay Street, this marshy forest is the headwaters of the Cuyahoga River, author of the greater Cleveland landscape. I’ve trekked out to this half-frozen field in search of the source of the crooked river. Like blood vessels that deliver oxygen to a web of capillaries throughout our bodies, rivers don’t issue from a single, definitive source. The fractal geometry of nature always finds a way to divide and subdivide until the line between a riverbank and dry land blurs into a wetland.

Although nature often evades our attempts to fit it into hard and fast boundaries, this landscape has remained the source of the region’s primary river for more than 10,000 years and will continue to fulfill that role well into the future. For all the books that have been written about Cleveland’s history, most ignore this ground truth: the river, the lake, and the climate have structured the lives of people here far more profoundly than the ephemeral relationships involved in economic and political systems. It is a lesson we’ve struggled to learn, despite having the information widely available for more than a century.

Standing out on this half-frozen field, it’s difficult to connect the weight of the river’s place in history to this landscape. If you have ever visited a historic battlefield, building or roadside historical marker, you are familiar with the underwhelming feeling of being a little late to the party. Yet, we should rethink unheralded spots like this one because this river, and the land it drains, have an important story to tell us. For the past 13,000 years, humans have made a life in the Cuyahoga watershed. In that time, a spectacular array of diverse cultures have provided different models for how to live on this land. The purpose of this book is to recover some of those experiments and consider them in the light of our present challenges.

Currently, one of our largest obstacles is one of the imagination. Modern Americans are enthralled by a linear view of history, where the present is the culmination and fulfillment of a long arc of progress out of barbarism. In this view, the further we go back in time, the worse things get. What use is history when the past is but the awkward list of misadventures of our species’ adolescence? Better to throw all that out like last year’s shoes.

Regardless of our preference for the present, though, we have more in common with the first humans who made a life in this landscape than we are willing to admit. Although the hunters I met at the headwaters of the Cuyahoga are equipped with modern firearms, and though their clothes (and acrylic nails) are composed of petroleum polymers, they are participating in the first economy humans brought to this landscape: earning a meal from the forest. If you are a reclusive city-dweller, you aren’t much different. When any resident of Cleveland turns on a tap, they are at the end of a long technological system that connects them to Lake Erie, the crooked Cuyahoga’s ultimate destination.

Sign Up to Receive the Cleveland Magazine Daily Newsletter Six Days a Week

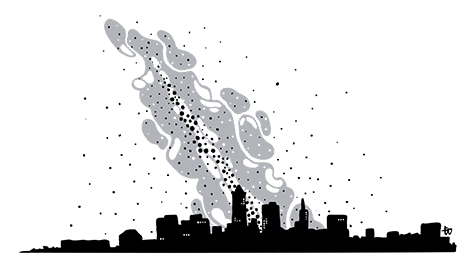

Of course, our recent history suggests that humanity has made a plaything of Northeast Ohio’s natural systems. Since the founding of Cleveland in 1796, we have dammed its rivers, poured so much fertilizer onto our lawns and crops that the lake turns green in the summer, and remade our shorelines and riverbeds to accommodate industry. We have even disrupted the day-night cycle, as the entire region burns as bright as a second sun each night with the help of nuclear power. We have created machines so loud that birds have altered their mating habits. We have chopped (or burned) down 95% of the state’s forest and drained a swamp the size of Rhode Island. We have also built fantastical complexes to entertain, educate, and feed our growing population. We have even set rivers on fire.

Despite all this, our seeming mastery over the environment is an illusion. Just because we can wrap ourselves in a technological cocoon does not negate the power of climate and geology to structure our lives. The river, lake and the land itself abide by their own laws, and we ignore them at our peril.

.jpg?sfvrsn=1a4cfb8c_1)

(Libby Geboy)

Consider the events of Aug. 14, 2003. The sun rose on fair skies, calm winds, and a comfortable 65 degrees F. It was a typical, late-summer day in Cleveland. Although the temperature rose to 87 by 2:00 p.m., nearly five degrees higher than the historical average, the gradual increase was well within the means of the power grid’s ability to accommodate it.

Accounting for what a power grid can handle is no easy task. It is difficult to accurately measure the present state of even a regional power system, which is why power grid operators employ complicated telemetry software. One such program, known as the “state estimator,” assembles all the instrument measurements within the system and projects estimated values for all the gaps between measurements at five-minute intervals. Imagine if your house had a thermostat in every room and a computer capable of calculating the temperature of your couch based on that data, and you will begin to have an idea of the complexity of the state estimator.

Just after noon, an engineer monitoring the power grid covering much of the Midwest noticed an anomalous reading. He discovered the software had erroneously included an out-of-service line as active, corrected the error and went to lunch. Even in an era of “smart” appliances, our machines still require a human touch, like mentally accounting for an oven that runs hot, a slow clock or a robotic vacuum that gets stuck under our bed. A system as technologically complex as the power grid also requires human engineers to account for the messiness of the real world. But on this day, the engineer did something even well-trained and well-educated people do all the time: He made a simple mistake.

In manually correcting the error, he forgot to reengage the interval setting, effectively freezing the data in stasis. Without subsequent iterations to relay real-time data into the software, the computers negotiating the complex electric grid for Cleveland were flying blind. The thermostat, so to speak, had been disconnected from the real world, and it entered a positive feedback loop. Over the next 15 minutes, computer errors accumulated and knocked out critical servers, tripping the FirstEnergy generating plant in Eastlake. When the plant went down, the grid compensated by pulling in energy from other plants, a protocol that puts an additional burden on the power lines that is normally well within standard tolerances. If you’ve ever experienced a flicker in your lights or a brownout, you’ve witnessed such a redirection of power.

Although we tend to think of our power grid (if we think of it at all) as a magical machine operated by faraway engineers, complex computer systems and lineworkers in hard hats, it’s also a real, material object. The lines are made of conducting metals like copper and aluminum. On particularly hot days, they can sag, sometimes dramatically, as the metals expand. The amount of current running through a line can also change the nature of the wires. The US Energy Information Administration reports that, on average, 5% of the energy transmitted through the grid is lost, some of it as heat. And the more energy coursing through a transmission line, the warmer it gets. On this hot August day, the power lines in Cleveland began to sag as additional current flowed through them. Under normal conditions, this is to be expected. It’s why line crews maintain wide clearance around our power lines: They stretch and contract with changing temperatures and conditions. Again, human labor is required to bridge the gap between our technology and nature. Unfortunately, when human labor is subject to economic imperatives, it doesn’t always meet its obligations.

RELATED: 76 Books that Arrived from Cleveland's Literary Scene in 2024

What happened next is the subject of some debate. What we know for sure is that after the failure of the Eastlake plant, multiple lines across Northeast Ohio made contact with tree limbs, resulting in a short circuit. When a line makes contact with an object, it triggers an automatic safeguard that takes the entire line out of commission. As the lines tripped and power began to flow through the grid in an increasingly chaotic manner, power stations went into safe mode—a type of electronic quarantine—to avoid the damage caused by the surges. Fail-safes and redundancies began to fall like dominoes as one city after another suffered a surge and a blackout. From west to east, the metropolitan areas of Detroit, Toledo, Cleveland, London and Toronto in Ontario, Buffalo, Rochester, Baltimore, and Newark all lost power.

Desperate to contain the cascade, engineers began to sever cities from the grid. Shortly after four in the afternoon, the international connection between Canada and the U.S. failed, and New York separated itself from the New England grid to prevent further damage. Over 14 million people in New York City were affected by the blackout, and many would remain without power until the following day. The headquarters of the United Nations went dark, and hundreds of subway cars were trapped between stations. Traffic signals throughout Manhattan blinked out, and people were trapped in elevators. With the terrorist attacks of 9/11 fresh in everyone’s memory, many reported feelings of panic and fear as their city was once again paralyzed by forces beyond its control.

The cascade of failures continued until it engulfed hundreds of power plants and substations, creating the largest blackout in the history of North America. Fifty-five million people across eight US states and the province of Ontario were affected. Ohio’s lakeshore in and around Cleveland faced some of the blackout’s more serious consequences. Cleveland Mayor Jane Campbell was surprised to discover the blackout’s far-reaching consequences in its earliest hours. When the city’s water commissioner informed Mayor Campbell that the people farthest from the lake would only have running water for about three hours, she asked, “Water? I thought the electric was out.” Without electricity to power pumps, though, water service ceased throughout the region, threatening a widespread humanitarian crisis.

Cedar Point amusement park lost power while rides were in motion. Staff were able to use generators to pull some of the frozen roller-coaster cars over their lift hills so gravity could work its magic. Magnum XL-200, one of the tallest roller coasters on the planet, had a car stuck on its 205-foot initial ascent, and the generators didn’t have enough energy to overcome that hump. A safety crew escorted frightened guests down the steel coaster, which offers a nauseating view under the best of conditions. Rumors swirled among the 30,000 guests at the park that Al-Qaeda had pulled off another attack.

As night fell, though, something incredible also took place: Millions of people across North America stepped outside into the warm summer night and encountered a dark sky free of light pollution. Amid the chaos and uncertainty, the curtain of civilization peeled back briefly and gave Clevelanders a momentary view of their home from a different perspective. The full depth of a night sky filled with stars, including the white splash of the Milky Way, wheeled over downtown. It was a sky that once greeted every resident of this land beginning with the first humans who arrived at the close of the Ice Age, before the age of gas and electricity extinguished the cosmic spectacle in the 20th century.

The soundscape changed, too. Without electricity, the night air was uncluttered by thundering air-conditioning units or commercial aircraft. Corner stores held cash-only blackout sales of cold drinks and ice cream, hoping to clear inventory. Neighbors gathered in quiet streets, in doorways, and on porches and shared what little information or terrifying rumors they had heard during the day.

With the exception of automobile traffic and the occasional generator, the sensory world became more intimate, briefly unmoored from our technological interface with nature. Through it all, plants continued to photosynthesize, bacteria continued their work of decomposing, our bodies metabolized food, and the Cuyahoga River flowed from the trickle near Hambden Orchard to its mouth on Lake Erie in Downtown Cleveland.

Clevelanders have a strange nostalgia for the 2003 blackout — a mixture of fear, excitement, boredom, and annoyance. Although the blackout imperiled their supplies, Pat and Dan Conway of Great Lakes Brewing Co. vividly remember how bright the moon appeared over their brewery that August night. The two celebrated the event by introducing Blackout Stout, complete with a label depicting Clevelanders gathered on a dark porch with candles and, of course, beer.

(Libby Geboy)

The loss of power was so complete it caught Clevelanders in every stage of life and death. Danielle Lannings was at lunch in her middle school when the lights turned the cafeteria black and caused the assembled students to scream in terror. Little Italy, which never lets an opportunity to party go to waste, had to call off its festivities for the Feast of the Assumption. And in Garfield Heights, Denise Samide was at the bedside of her dying mother at Marymount Hospital when the power went out and the backup generators kicked in. “It was surreal,” she said of the experience.

In the blackout’s immediate aftermath, a bilateral, American-Canadian commission produced a 238-page report to better understand how a seemingly small problem snowballed into such a colossal failure. Through interviews and an investigation, they found FirstEnergy had been negligent in clearing tree limbs from the “designated clearance area” around power lines. Multiple power lines in northeast Ohio tripped on the afternoon of Aug. 14 because the company had failed to perform simple tree-trimming maintenance. What began as a software glitch manifested into a real-world crisis, all on account of a few trees in Parma and Walton Hills. The report noted that tree-to-line contacts “are not unusual in the summer across North America” because most tree growth occurs in the spring and summer months. Despite our astonishing achievements in asserting technological control over the natural world, we still have trouble accounting for something as simple as the annual growth of plant life.

Assigning a singular cause to such a large event is as hopeless as finding the exact spot where the Cuyahoga begins. We can get you in the ballpark (or marshy field), but ultimately, it’s kinda everywhere. Fussy software, human error, some tree limbs in the wrong place at the wrong time, and decades of deregulation increased the odds of a system collapse. FirstEnergy had spent the previous years focused on buying out competitors rather than maintaining safe clearance around their power lines, and government regulators lacked the power to levy fines against negligent practices because political rhetoric had associated government regulation with tyranny.

The 2003 blackout is a story of a complex, technological system coming into contact with nature. It reveals some of the consequences of constructing a built environment with little regard to how it interfaces with the land beneath our feet. Sadly, this is not a new story in Northeast Ohio. Fortunately, our history also holds lessons we could benefit from if we desire to forge a less adversarial relationship with our environment.

In 1961, the historian Lewis Mumford pondered the role of the city in human history with the goal of solving the emerging problems of urban decay in America’s great metropolises. Mumford believed humans had reached a fork in the road — we would have to decide if we wanted to continue developing “the now almost automatic forces” we had set in motion to live in comfortable bliss or choose a life of engagement with our communities and the natural world that would lead to the development of our “deepest humanity.” He feared the allure of comfort from an automated landscape would “bring with it the progressive loss of feeling, emotion, creative audacity, and finally consciousness.” Mid-century American intellectuals like Mumford didn’t spend much time thinking about the middle ground between utopia and apocalypse, which is where most of us live.

Mumford’s grim perspective on the future trajectory of the American project would be shared by a generation of urban reformers and cultural critics. Such criticism often came with a sense of fatalism about reform efforts, including the cruel belief that the people who lived within failing cities somehow deserved their fate. If you are from Cleveland and of a certain age, you probably have a chip on your shoulder about how your hometown became a caricature of everything wrong with urban life. Lest we forget, this criticism was also rooted in a real crisis. Prior to the environmental reforms of the latter 20th century, the city had entirely corrupted the elemental foundations of life: our water, air, and soil.

By raising the stakes to apocalyptic levels, 20th-century reformers like Mumford set some of the battle lines for the culture wars of the present. Although his rhetoric failed to convince Americans, his observation about the relationship between the city, communities, and the natural world remains true. Today, the city of Cleveland is bound to nature, despite our best efforts to liberate ourselves from its limits.

RELATED: New Water Trails Prove There's More to Cleveland's Waterways than Lake Erie

The present plays a cruel trick on us. As a landscape, the very architecture of the city crystalizes some elements of the past and ignores others. The glow of our streetlights obscures the heavens above our heads, and the turn of a faucet hides our connection to the lake and the river that feeds it. We should interrogate and reexamine our city to reveal a complete picture of the land and our place in it. This book is an exploration of the history of our built environment and how it structures our relationship with the natural world. It’s also an attempt to uncover glimpses of the former world — the land and the people who lived on it before Moses Cleaveland arrived in 1796. Two inescapable facts emerge from this deep-time perspective. First, the human relationship with the land goes back further than our memorials and statues suggest, at least as far back as the last ice age that created our Great Lakes. Second, our complex cultural and technological achievements obscure our most critical resource: the land beneath our feet.

Today, Cleveland’s relationship to the natural world is stronger than it has been for nearly two centuries. Fish species and raptors are returning to the Cuyahoga River, critical habitat is being protected, and a mixture of scientists, activists, and volunteers are measuring the impact of the built environment on wildlife in order to work with nature, not against it. Unfortunately, the bar for a healthy relationship with the natural world is quite low. The last two centuries haven’t given us many high-water marks of environmental resilience. Major challenges remain, such as the maintenance of our critical infrastructure and preparing for the largest shift in climate since the Pleistocene epoch. Hopefully, it won’t take another systemic collapse for us to engage with the world around us and decide what kind of city we want to live in.

About The Author

(Derrick Turner)

Jon Wlasiuk was born in the Black Swamp region of northwest Ohio and earned a PhD in environmental history from Case Western Reserve University. Also the author of Refining Nature: Standard Oil and the Limits of Efficiency, he has taught at colleges throughout the Great Lakes and lives in Cleveland’s Slavic Village neighborhood.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5