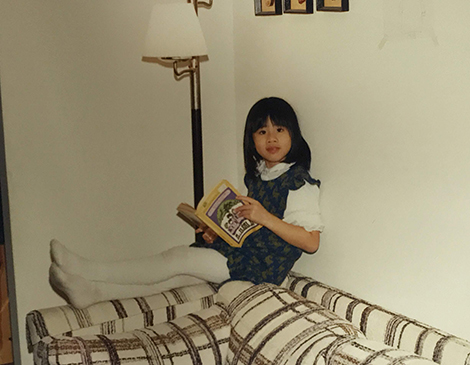

Ng was 11, or maybe 12. She and her sister were waiting for a bus near Tower City, along with their aunt and uncle who were visiting from Hong Kong.

“This man came up and was screaming at us,” Ng recalls. “And he was really screaming in our faces and saying things like, just go back to, you know, Vietnam or wherever you came from. And he spat at the ground.”

Experiencing a sudden display of hate was unnerving; it came out of nowhere. But so did an act of bravery.

“There was a woman at the bus stop,” Ng says. “And she intervened. And she said, ‘Why don’t you leave them alone? Why don’t you just, you know, take a step back’ and then he began yelling at her, which was, I think, her goal, and then the bus came, and we got on it. But that was I think maybe one of the only times that a bystander has ever intervened in a case like that. And it strikes me now looking back how brave that woman was, and how grateful I am to her.”

In Our Missing Hearts, Ng explores how bystanders can make a difference, how in our increasingly polarized society, she believes they must. In some ways, the novel itself is a form of bystander intervention. Although she began writing it as an exploration of a parent-child relationship, her newest novel took a darker turn after the 2016 election.

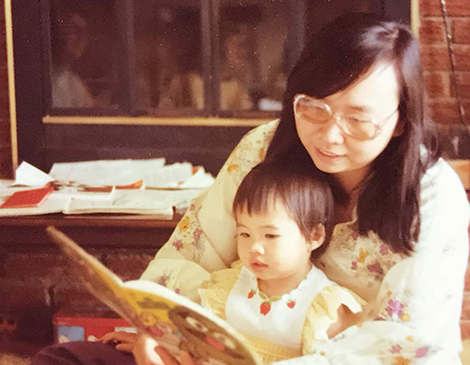

“That started to raise a lot of questions for me about how you raise a child in a world that feels like it’s got so much hate in it,” Ng says. “How you raise a child, for me, in particular. I’m raising a multiracial son.”

While it’s possible some readers will find Our Missing Hearts too political, Ng says her other two novels also questioned the way society functioned. They, too, delved into issues of discrimination and other injustices.

“The older I get, the more I realize that my life is political, whether I want it to be or not because I walk around in this body,” Ng says. “I am an Asian American woman. I am a child of immigrants.”

In her mind, she isn’t moving through the world as an Asian person. She’s moving through it as herself. “But then there’s a moment where you might be on the bus, or you might be in the train station and someone calls you out on it, and they let you know that you’re not like us or you’re not welcome,” she says. That’s the moment when you realize the world sees you differently than you see yourself.

In Our Missing Hearts, 12-year-old Bird Gardner is constantly reminded of his differences. He is the son of Margaret Miu, a Chinese American poet who has disappeared. Bird has never read her poems because they too have disappeared — they were deemed too dangerous to be read in the authoritarian society America has become. Despite his father’s insistence that Bird forget about his mother, Bird goes in search of her instead. Unlike Ng’s other two books, Everything I Never Told You and Little Fires Everywhere, which take place in the 1970s and the 1990s, respectively, Our Missing Hearts takes place in a dystopian future, where actions questioning American patriotism could result in harsh punishment, including the removal of children from their parents.

Taking children (the “hearts” in the title of the book) — or threatening to do so — is one way the government tries to control its critics. Ng’s readers learn about the historical precedents for this in America at the same time Margaret does. Children were separated from their parents during slavery and at Indigenous boarding schools. More recently, children have been taken from their parents at the border and then kept away from them, revealed by The Atlantic as a planned effort (not an unfortunate result) of the Trump Administration’s mission to dissuade migrants from entering the U.S.

“There was a long history of children taken, the pretexts different but the reasons the same,” Ng writes. “A most precious ransom, a cudgel over a parent’s head. It was whatever the opposite of an anchor was: an attempt to uproot some otherness, something hated and feared. Some foreignness seen as an invasive weed, something to be eradicated.”

For this novel, Ng embarked on an informational journey through dense historical books about living under tyranny in occupied France and McCarthyism in America. She filled notebooks and digital files with her research on the totalitarian regimes of the past and threats to free societies today. In an author’s note, she explains why she drew inspiration from actual news and history by quoting Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale: “If I was to create an imaginary garden I wanted the toads in it to be real.”

The time after the 2016 election gave Ng plenty of “toads” to inspire the bleak society in which Bird lives, including political polarization and social unrest. It was also a time of rising anti-Asian sentiment. Nearly 11,500 incidents of hate directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders were reported to the hate-

tracking coalition Stop AAPI Hate between March 2020 and March 2022. Its leaders have followed the wave of anti-Asian hate since the pandemic, blaming it in part on the rhetoric of some politicians.

Shaker Heights resident Samantha Chin, Ng’s friend since fifth grade and the mother of a 9-year-old daughter, often talks with her about what it’s like to raise a child of Asian heritage in America today. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chin’s daughter was subjected to a racist joke at school. “That never would have happened when we were in school,” Chin says. “It [society] seems to have regressed in some ways.”

That’s one reason Ng felt she had to set Our Missing Hearts in the future.

“I couldn’t write about what was happening now,” Ng says. “I felt like I needed it to be a world that was not quite ours but was maybe five degrees off of ours. ... I think it’s difficult to write about things that are right in front of your face. And in some ways, I think that speculative fiction, whether it’s dystopian, whether it’s fantasy, whether it’s science fiction, whatever it is, it can allow you in some ways to hold things at a slight distance, and you can see them a little bit better. You can understand them a little bit better, in a way that you couldn’t if you’re being told, this is our world.”

For Little Fires Everywhere, which became an original series on Hulu starring Reese Witherspoon and Kerry Washington in 2020, Ng crafted a provocative portrait of Shaker Heights, where she attended Shaker Heights High School in the 1990s. Even in that community, which prided itself on its diversity and progressive politics, racism simmered beneath the surface in quiet, powerful ways. In the “From the Archive” podcast, which aired in 2017, Ng explained how she worked to achieve “a middle distance” — one that lets in information gleaned from personal experience but does not rely exclusively on it.

Chin remembers Ng talking about race in high school. “When we were in school, it was ‘no one sees race’ and that was how people dealt with race,” she recalls. Ng always lent her support to people who felt marginalized, Chin says. She’s always had “a protective spirit.”

In Little Fires Everywhere, as well as in her new novel, Ng provides a window that looks to readers like a mirror, one where we recognize our wrinkles but also our father’s good hairline or why our classmates voted us “best smile” in high school. Our Missing Hearts shows America’s tendency toward nationalism as well as its respect for resistance.

The bystander at the bus stop is one of many ways Cleveland influenced the novel. The city’s legacy of public art is another.

As a high schooler, Ng spent many days at the Cleveland Museum of Art, sketching her favorite works. Only later in life did she realize how unusual it was that you can go to the world-class art museum for free.

“That was sort of one of the things that I was thinking about when I was writing Our Missing Hearts — is that sense that art can be all over the place,” she says. “And it can kind of come at you and shake you out of your normal complacency. It’s like a little jolt. It wakes you up.”

She says one of the actions in the book was inspired by Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors installation in 2018, where the Japanese artist wrapped trees outside CMA in red fabric with her signature polka dots.

After Little Fires Everywhere came out in 2017, Entertainment Weekly called Ng “the novelist of the moment” for the way she confronts racism in her work, but that characterization shortchanges her work. There is a timeless quality to the compassionate way she writes even her most unlikable characters. Their outlooks and biases have devastating effects on society — and usually on Ng’s always-relatable main characters. But she takes the time to show us who they are. We are reminded of the complexity of every person, no matter how despicable their actions or how blind they are to their bias.

All three novels have one thing in common. Ng goes into the most terrifying place for any parent regardless of race, ideology, nationality or gender — the place where they are separated from their child. This is where her window feels like a mirror again.

Perhaps we should lean into our fears, like the best writers do, so we can move beyond them. In her novels, Ng answers the questions we don’t dare ask. She shows there is life after loss. And, in this novel especially, after fear and hate, too, as long as we are willing to intervene.

“I think a lot about that woman in the middle of Public Square,” Ng says. “One person stepping in can actually make a difference.”