He has no head and no immediately identifiable characteristics. The Draped Male Figure stands relaxed, an arm folded across his belly, the other at his side. His Greek robes gently fall around his physique like those of a noble. Historians speculate if he may be a Roman emperor, possibly Marcus Aurelius, though he neither depicts a heroic male nude nor a military leader, like others of Roman emperors.

Whoever he may be, the 6-foot-4 Greco-Roman bronze statue has seen more than 1,800 years of history unfold and has drawn curiosity from art observers since the 1960s. Recently, his journey landed him in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s rotunda.

Before a New York City art dealer sold the statue to the CMA in 1986, the suspected Roman emperor toured museums in the United States. It entered the art market with three heroic nudes, two headless and one with the head of Lucius Verus, indeed a Roman emperor. The statues were rumored to be from a small archaeological site known as the Sebasteion in Bubon, Turkey.

Yet, allegations emerged that the piece was stolen. The CMA wasn’t so sure.

So, was this Cleveland piece from the Sebasteion? How did it get to the U.S.? Was it looted? Could the CMA ethically keep it? Questions swarmed the statue’s fraught history, until new information came to light.

It’s not an isolated occurrence. Curators at art museums in Northeast Ohio grapple with the evolving ethics of art acquisition.

In the case of Draped Male Figure, Turkish authorities discovered that local villagers had looted the Sebasteion site in the 1960s, selling artifacts in the art market through various intermediaries without proper documentation until it was put to a stop in 1967.

“It was not known for sure,” says Seth Pevnick, curator of Greek and Roman art at CMA. “One of the reasons that it was thought to have come from there is that around the same time that these statues showed up in the art market, Turkish authorities discovered a large-scale bronze statue of what we call a heroic male nude. Very different from the statue that’s here, but they discovered it lying hidden near an archaeological site.”

Turkish officials continued excavating Sebasteion with the help of local villages to find the missing statues, according to The New York Times. That evidence was sent to the Antiquities Trafficking Unit of the New York District Attorney’s Office and shared with the CMA in 2023, indicating that the base of the statue at Sebasteion had been found, inscribed with the name Marcus Aurelius.

With that discovery, Turkey staked a claim of ownership for the Draped Male Figure. The district attorney’s office asked the CMA to return the statue to Turkey, but Pevnick and the museum itself initially rejected it, believing the evidence provided wasn’t accurate or sufficient enough to claim ownership.

After a lengthy back-and-forth, the district attorney’s office informed the CMA that if it did not return the item, it would seize it and send it to Turkey. Lawyers for the Museum quickly filed a lawsuit to prevent that until more conclusive evidence could be produced.

The battle over the bronze statue continued over the next two years with 3D models, molds of the statue’s feet and, finally, an isotope analysis which revealed a perfect match with a partially crushed base discovered at Sebasteion — not the one belonging to Marcus Aurelius.

“All of these things being considered, it seems extremely likely that this statue was discovered at that site by looters in the 1960s and that it stood on an uninscribed statue base there,” says Pevnick.

Still today, archaeologists have yet to find any inscriptions on the statue base. Who the statue is remains unknown. Pevnick hopes that historians will continue to study it. Just not in Cleveland.

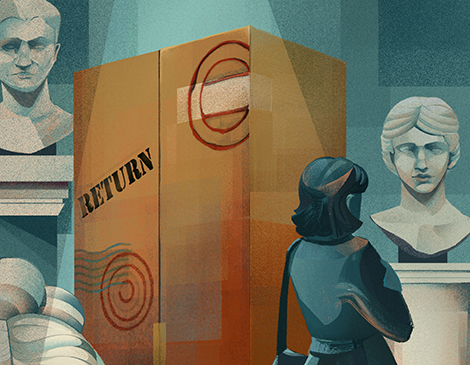

The statue was returned in July, after Turkish authorities allowed the museum and its visitors one last viewing over a four-month period.

“If an object is stolen, it is always stolen,” says Pevnick. “The [museum] can’t be the rightful owners of that object.”

A mystery solved. But issues like this aren’t uncommon in the museum world. The CMA and other museums regularly encounter ethical questions about the origins of artworks in their collections.

Two years ago, Libya’s Department of Antiquities approached the museum with publications suggesting that a two-foot-high black basalt statue of a standing man was excavated at a Libyan archaeological site in the city of Ptolemais and belonged to a museum that had been looted or lost during the British occupation of Libya in World War II.

For over eight decades, Libya was unaware of the location of the Ptolemaic Statue of a Man. Unknowingly, it was sitting in the CMA since 1991.

“They were absolutely right. It’s almost certainly the same statue,” says Pevnick. “We don’t know exactly what happened to it for a span of some years. In the end, the most important thing is that it rightly belongs to the state of Libya.”

CMA plans to return the Ptolemaic Statue of a Man to its home country. In the meantime it will stay at the CMA on loan for five years.

When acquiring new art, the CMA, Akron Art Museum and Oberlin’s Allen Memorial Art Museum use established standards, as outlined by the American Alliance of Museums, that require curatorial rigor to be an accredited museum. Fewer than 5% of museums in the U.S. are accredited.

Museums conduct provenance research on their historical collections of artwork acquired before 1970. Anything acquired by museums in the West after 1970 is accompanied by proper documentation, since the United Nations adopted laws prohibiting and preventing illegal sales and transfers of cultural properties.

However, a lack of funding and staff remains an issue for organizations working to ensure that their collections are thoroughly documented and acquired ethically.

This only became the established standard in Western museums in the 2000s, says Alexander Herman, director of the Institute of Art and Law. That’s why cases like the Draped Male Figure and Ptolemaic Statue of a Man, acquired by the CMA after the 1970 rule, are happening.

The CMA has a collection of more than 65,500 objects, with 19 curators on staff. Akron’s collections comprise over 7,000 objects, with a staff of five curatorial members. The Allen Memorial Art Museum has 15,000 works and three collection curators.

“Museums do as much as they can with the resources available to them,” says Katherine Solender, the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s interim director. “For all museums with historical collections, gaps in the record of provenance certainly present challenges. Sometimes the balance between what is legal and what is ethical is difficult to maintain. What may have been legal at the time of acquisition may now be considered unethical. Institutions have to contend with that tension.”

Due to these limited resources, museums often rely on external organizations, nations or databases like the Art Loss Register and the International Foundation for Art Research for provenance research.

“We’ve participated in databases of artwork providing what’s in our collection, created before and during the World Wars, just in case there should ever be a claim or link of ownership that it might’ve been stolen or otherwise improperly transferred,” says Jeffrey Katzin, senior curator at the Akron Art Museum.

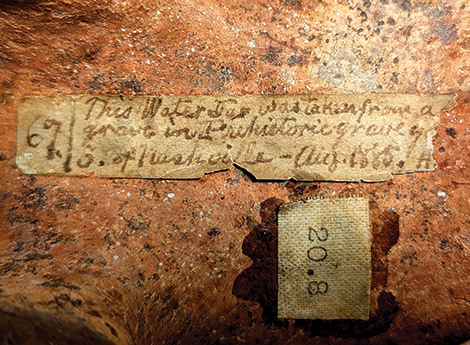

Water Bottle in the Shape of a Bird, a piece in the Allen Memorial Art Museum since 1920, was gifted by the wife of an Oberlin College alumnus who looted the piece in 1885 from a grave in Nashville. After staff worked with a consultant and an associate professor of anthropology at Oberlin College, the piece was discovered to be from Mississippian culture, dating to 1350 to 1450. It had previously been identified as Peruvian. The Allen contacted three Cherokee tribes to whom they will jointly restitute the item.

Provenance research is a continuous responsibility for curators. But in recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic allowed curatorial teams to devote more time to provenance research while they had fewer visitors. In this time, Akron Art Museum curators worked through a large spreadsheet of every artist represented in the museum’s collection.

It’s not just ancient sculptures or paintings that can cause controversy, but also contemporary art created after the 1970s that raises ethical questions for artists and museums.

The Akron Art Museum, though it specializes more in contemporary art than historical art (its collection spans from 1850 to the present), still ran into its own ethical conundrum with one of its most popular pieces.

Linda, a large-scale photorealistic portrait acquired by the museum in 1982, created by the late Chuck Close, was temporarily put back into storage in 2017 following sexual harassment allegations made by women with whom he worked closely.

“[It was] a question for us of what we wanted to do with this painting, which is really, really very popular at the Akron Museum,” says Katzin.

In 2017, managers discussed putting a disclaimer near the piece. The museum instead kept it off view until Katzin found a home for it. He displayed it in a salon wall of numerous portraits, arranged in an irregular pattern — removing emphasis on Close as an artist, and instead showcasing a range of images.

“Because it’s part of this collective, there isn’t as much of a call to tell Chuck Close’s specific story and to talk about his individual creativity,” says Katzin.

While historic art is debated in terms of where it should belong, Katzin knows where Linda belongs.

“The painting belongs to our audience, the people of Akron, as much as, or maybe more than, it would belong to Chuck Close and his legacy,” Katzin says.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.