New Technology Helps Tell Holocaust Survivors' Stories

by Kate Bigam | Dec. 3, 2018 | 3:00 PM

Stanley Bernath flew to California earlier this year to share his story. The 92-year-old Lyndhurst Holocaust survivor, born in Romania, sat in a studio outfitted with 100 cameras capturing his image from every angle. Over 12 hours, he recounted his experiences as a teenager in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, as well as his life before and after the Holocaust. He recalled a Nazi guard who dropped scraps of food to him from the watchtower above. He remembered his emotional reunion with his family after the camp’s 1945 liberation.

For decades, Holocaust survivors have recorded written, oral and video testimonies of their experiences during World War II. Now, the USC Shoah Foundation, founded by filmmaker Steven Spielberg, is preserving stories using hologram technology.

The foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony project creates lifelike, responsive versions of Bernath and other survivors based on extensive personal testimonies. At Beachwood’s Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage, guests can learn from Bernath’s simulation in beta tests of the tech.

“[Survivors] are trying to describe what they went through in a way that a child can absorb some of the information and carry that message with them,” says Ken Liffman, chairman of Maltz’s Survivor Memory Project. “They’re taking their tragedy and trying to turn it into an educational experience.”

Driven by artificial intelligence, the Bernath simulation answers visitors’ questions about his Holocaust experiences, providing lifelike interactions with an actual survivor.

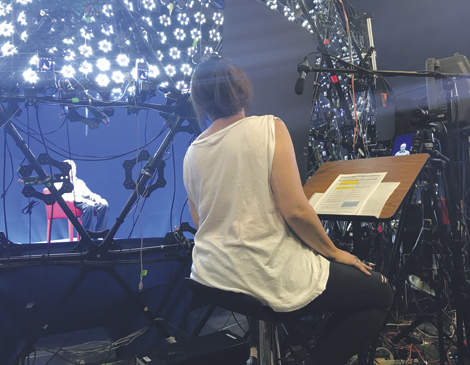

Maltz Museum guests can ask questions of Bernath’s likeness, which appears on a large screen in the museum’s theater. Bernath appears sitting in a red chair before a black background; when the lights go down in the theater, it looks like he’s sitting right in front of you. “It looks like a fully formed human being,” Liffman says of the simulation’s visuals.

A museum docent can assist in framing questions so they are understood by the AI that drives the exhibit. Ultimately, the AI grows and evolves with each question, resulting in more comprehensive, lifelike responses. The interactive survivor biographies are available in museums across North America.

“You see tapes of children talking to these interactive technologies, and they’re entranced,” Liffman says. “Their knowledge is exponentially increased about the Holocaust and their desire to learn more.”

Bernath is one of 15 survivors nationwide who had his story made into a Shoah Foundation interactive biography so far. Time is of the essence in recording survivors’ stories, given their advanced age. One of the survivors who provided testimony has since passed away.

“[This project] will never replace our survivors,” says Dahlia Fisher, the museum’s director of external relations, “but what we can hope for is that it will simulate the experience enough that, into the future, it keeps testimony alive in the education of students and adults.”

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5