Print Club Of Cleveland Turns 100

by Ken Schneck | May. 6, 2019 | 12:00 PM

Before the internet or newspapers, there were art prints, the original mass media. First made in Europe in the 1400s, prints made art accessible, allowing artists to reach wider audiences while reproducing works, capturing historical events and experimenting with political or devotional themes. The largest single print supplier for the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Print Club of Cleveland has encouraged the preservation of prints since the early 1900s. On May 5, CMA honors the partnership with A Lasting Impression: Gifts of the Print Club of Cleveland, an exhibit honoring the Print Club’s centennial anniversary. For a sneak print peek, we asked Emily Peters, CMA’s curator of prints and drawings, to preview four works from the show.

Rembrandt and His Wife Saskia (1693), Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt stands as a singular influencer in printmaking’s history. The Dutch master’s work had the quality of spontaneous drawing, a departure from contemporaries who used the medium to simply reproduce images of their paintings. In this piece, he likely positioned himself in front of a mirror to sketch a self-portrait with his wife right behind him. “Compositionally, he placed himself close to the picture plane, which creates an intimacy and immediacy,” says Peters. “Through the print, he creates an interesting connection with the eyes.”

Savarin Suite: Savarin 5 (1978), Jasper Johns

Now in his late 80s, Johns is widely considered one of the greatest living printmakers. In this print, the final in a suite of five, he uses his paintbrush can as his stand-in for a kind of self-portrait, embedding himself within the work. “The way that he manipulates the print technique, it’s very painterly with obvious brushstrokes,” says Peters. “It’s very tactile in person.”

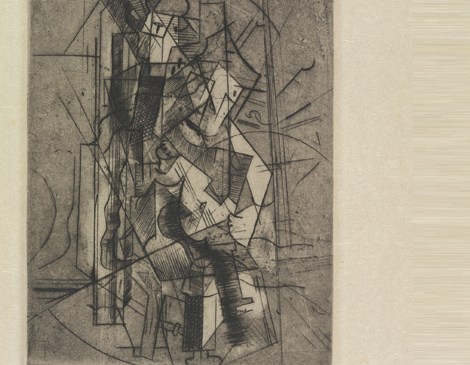

Man with a Guitar (1915), Pablo Picasso

The Spanish genius’ prints comprise work complementary to his paintings and sculptures. This piece was created during his Cubist period — an art movement he co-founded — when he was experimenting with the ideas of balance and space. “Using dry point and etching, he conveys murkiness and inkiness to lend to this idea of breaking the planes apart,” says Peters. “He is using the print medium to explore the themes of Cubism in black and white.”

Esterel Village (1890), Edgar Degas

Although most associate Degas with his iconic depictions of ballerinas, he was also an innovative printmaker who created work in this form to workshop new artistic ideas. In this landscape, Degas recreates a scene he saw from the train on his way to Paris. Look closely to see where he left some of his fingerprints as he applied ink directly onto the copperplate. “You immediately get a sense of movement, as you feel the quickness that you get when you go by something on the train,” says Peters.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5