Picasso and Paper at Cleveland Museum of Art Is Worth the Wait After Pandemic Delay

by Lynne Thompson | Nov. 22, 2024 | 3:18 PM

Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art

Picasso and Paper was a victim of COVID-19 circumstances. The pandemic shut down the exhibit a mere 51 days after its Jan. 25, 2020, debut at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, then postponed its Sept. 22, 2020, opening at the Cleveland Museum of Art indefinitely.

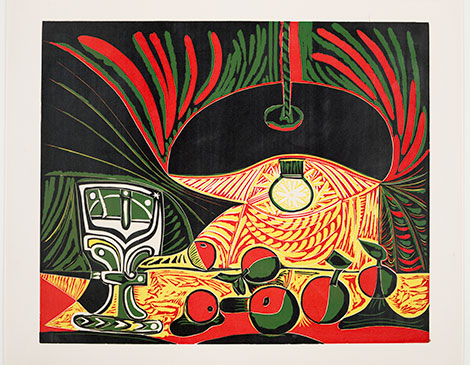

But the show’s Dec. 8 opening at the Cleveland Museum of Art is well worth the wait. A staggering 278 works depicting famed Spanish artist Pablo Picasso’s versatile use of paper — a collaboration between the Royal Academy of Arts, Cleveland Museum of Art and Musee National Picasso-Paris — will be on display. Together, they illustrate how Picasso challenged the idea of art as an accurate representation of the world via a material, generally affordable and easily accessible, in which he could be his most experimental, says Britany Salsbury, the Cleveland Museum of Art’s curator of prints and drawings.

“He explored the idea of vision, of perception and developed Cubism, which was a movement that abstracted a subject rather than represented it,” she says.

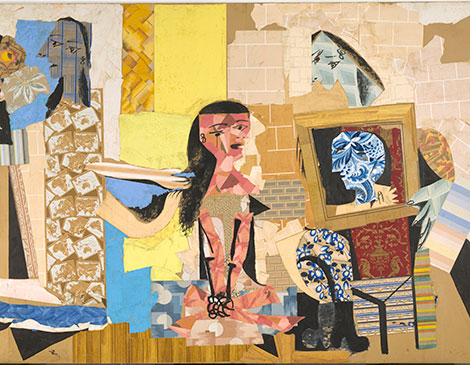

Among the 224 works loaned by the Musee National Picasso is “Women at Their Toilette,” a large (9 13/16 by 14 1/2 feet) collage of cut-and-pasted papers that many consider the star of the show. Stringed instruments, another of Picasso’s favorite subjects, are represented by the collage “Violin” and the paper sculpture “Guitar.” Among his sketchbooks are multiple studies of his famous paintings “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” and “La Vie,” the latter of which is in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s collection.

“He would never just settle on [a composition] looking a particular way,” Salsbury says. “He would question what it would look like if he changed this seemingly minor aspect of it.”

Salsbury says some substitutions were made when works became available after the shutdown. (She explains that art on paper is light sensitive and generally displayed for three months followed by five years in the protective darkness of storage.) They include the Cleveland Museum of Art’s “Nude Women,” a series of nine lithographs that show how Picasso gradually turned an initial realistic image into an abstractly Cubist one. “Boy With Cattle,” a drawing on loan from the Columbus Museum of Art, will be displayed alongside other works from Picasso’s Rose Period (1904-1906) in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s collection.

There are also works by Picasso’s romantic partners, women who often served as collaborators: photographs by the French photographer and painter Dora Maar, and drawings by French painter Francoise Gilot.

“We have two examples where Picasso and Gilot are looking at the same subject and realizing it similarly but very differently,” Salsbury says. They help depict Picasso “not necessarily as this isolated genius, but as someone who made incredible contributions to the history of art thanks in part to the people he worked with and who surrounded him.”

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5