On Creativity: Ray Flanagan, Cleveland's Rock 'n' Roll Poet

by Dillon Stewart | Feb. 19, 2021 | 6:30 PM

Ray Flanagan

Ray Flanagan has heard the song about a poet who died in the gutter — and if it’s about him so be it.

“I’m pretty OK with that,” says the songwriter when asked if he’d be OK with producing a body of work that he’s proud of but that no one ever hears, a sort of if-the-tree-falls-in-the-forest-type question. “The satisfaction for me is to make things. I’m happy that it’s out and been said, and I don’t have to worry about that anymore. If people want to find it 100 years from now. It’s there.”

Currently, however, there isn’t much there, at least in terms of recorded music.

Since getting his start playing in bands at the Tri-C High School Rock Off, the prolific 28-year-old has written a vast body of work, played around 150 gigs a year at farmers markets and coffee shops on his trusty acoustic guitar and rocked local festivals

such as Brite Winter and Burning River Fest on his Fender Telecaster with band Ray Flanagan & The Authorities.

But he’s also a perfectionist. Though he’s recorded others, his only full album currently available on Spotify, 2019’s Passerby, is a sparse, mostly acoustic rumination on love, longing and life. It’s a really good example of his lyrical and fingerpicking prowess, but it shows only one side of what Flanagan does. He’s grown discontent with the others and pulled them down.

But since the gig economy dried up, Flanagan has spent his pandemic year working on self-made recordings that sound far from homespun. In 2020, he released singles such as the haunting, political “The Arsenal,” an EP Our Year In Purgatory about, well, you know, and a topical collaborative EP Down Time with mentor Brent Kirby. This year, he’s vowed a release per month, kicking off with January’s “Soul On Down” and February’s “Strange Winter,” which comes with an instrumental B-side that nods to his AC/DC fandom. On March 5, he’ll release “When You Love Somebody” and “As Long As You’re Close."

These new songs show more than a change in production philosophy for the fastidious Flanagan. They also demonstrate a more adventurous sound and an artist using his vast knowledge of rock ‘n’ roll to paint freely with its many tools, from the fuzzy guitar jabs of “The Arsenal” to the beehive bends of “Strange Winter” to the Otis Redding-indebted vocals on “In The Days To Come.”

“If I was ever going to do at-home recordings, now is the time that makes sense, when we’re held up in our homes,” says Flanagan, who would still prefer to work with a recording engineer. “A record is just a documentation.

This is a true reflection of what it is. This is me in my room with my guitars.”

Here Flanagan shares thoughts on his writing and recording process, the uncertain future of performing live, his complaints about Spotify and social media marketing, and more.

On Being A Cocktail Napkin Writer

I’m always just recording voice memos and writing notes in my phone. I’m always putting ideas down, and they’re like scribbles. Sometimes I make myself do the work. I think that’s

probably a good way to be about it, but I’m not that way naturally. I’ll get a line or two or a melody, and I’ll be like, I actually want to write that. Once you have a form, it’s kind of just like filling in the blanks. I

just follow what I’m interested in. A lot of people say you should always follow an idea to completion because you don’t know where it’s going to end up. I don’t like to force stuff. I like when it just comes out.

On Writing About Cleveland

This is probably heavily inspired by Bruce Springsteen and his thing with New Jersey, but there’s something about intimately knowing an area. A lot of [the details and imagery in his] stuff goes over

my head because it’s actually foreign to me. I like being part of the landscape in Cleveland and feeling like one of the trees here. Who better to tell you about Cleveland than somebody that’s from here? And that’s not like my songs

are all about Cleveland, like tourism wave the flag, but it’s just that I’m passionate about the people here. There’s so much to write about if you just look around where you’re living. I don’t feel like you can ever

run out.

On How To Write A Song If You Never Have

People write songs all the time they just don’t consider it. Just think about what you feel and what you hear. Anybody can write a song about a tree or a cloud. It’s mostly just

about having the confidence to take the first step and present your own idea and say what you think or feel about something.

On Listening To Your Subconscious

I didn’t even know what [“The Arsenal”] meant. It just sounded f---ing sweet. That’s one where I just had that line, the chorus, and the verses were really just coloring it,

playing with words. It sounds like poetry to me, and if it sounds like poetry, that’s what it is. I think your subconscious is always coming from somewhere, and you got to follow it. You can figure it out later a lot of times.

On Open Mics

The biggest thing for me this year is that COVID killed the 10x3 [a songwriters’ showcase hosted by Brent Kirby at The Brothers Lounge in Cleveland. It’ll probably never come back. That’s where

I came up in 2011-2012. I would play as much as I could, and I’d never show up unless I had three new songs. There would be nights where I’d play with 7 of the 10 people. Eventually, Brent realized I could play guitar, and he’d

ask me to sit in. The 10x3 was coming up on 10 years. It’s the true end of an era. I think open mics are very important in terms of fostering community. I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now if it weren’t for open mics.

On Putting Your Art On Spotify And Facebook

We spend all this money recording on the best equipment we have access to, and we get all excited about what we're hearing come back through the speakers. And then we’re just going

to put it on Spotify? I put this “506” song on Spotify that’s just an iPhone recording [on which he mumble-sings “506, 507”]. My point of doing that was to show that now this voice memo is on the same platform with Thriller.

Bandcamp rejected it for being too low quality. Bandcamp is cool because they let you download the .WAV file, the exact high-quality file I get from the mastering guy. But when people complain about Spotify not paying artists, it’s like why

should they pay me anything for “506”? We feel trapped by the social media platforms, too. My artist page has 2,000 followers, and I’m lucky if I get five likes — even when 500 people saw it. I shouldn’t know stuff like

that, man. Thinking about those things discourages you from doing it again. The risk reward of posting something you poured your heart into and the algorithm decides [people don’t want to see it], and the algorithm is probably right! I feel

so crazy right now because I’m like what do I do with all this stuff I’ve spent my whole life working on. I feel like it’s disrespecting my art to put it on these platforms, but I don’t know what else to do because you want

to connect with people. You’re kind of forced to play by their rules.

On Being A Working Musician

There are actually a lot of working musicians in Cleveland, like Brent Kirby, Becky Boyd and Austin Walkin’ Cane. I think I seem odd because I’m one of the few younger people. We’re the

generation of side hustles. And because it’s rare to be a working musician that’s also an original artist, at least publicly.

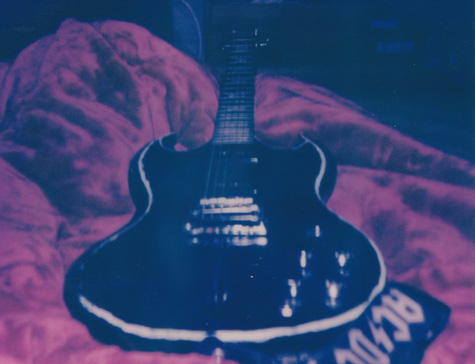

On Taking Pandemic Polaroids

My pandemic hobby was taking pictures with Polaroid cameras. It was nice for my brain to go in a different direction. I have stacks of pictures I took. I love them because they’re the original instant

gratification. Right now, I can’t afford it because it’s like $20 for eight shots! When I was learning, I was just blowing through film. You have to get the lighting right and stuff, but they’re meant to be an every-persons’

thing. It’s got its own grainy imperfections that make it seem like its alive. You could take 100 pictures with your phone, and it’ll never look as cool as that.

On His Love Of Metal

This past year, I’ve been more in touch with who I am and what makes me happy musically and artistically. I’ve been playing a lot of metal. I still love a lot of that stuff. I hear a lot more of Judas

Priest’s Rob Halford in the lyrics of “The Arsenal” than I do Bob Dylan or Neil Young, even if it has the Tom Petty, layered acoustic guitars. When Eddie Van Halen died, I was thinking about how I don’t really cite him as an

influence, but Van Halen had a huge influence on me. I feel like that’s a thing that I shouldn’t try to hide as much because it’s what makes me who I am for better or for worse. I just want to be truthful and be who I am.

Dillon Stewart

Dillon Stewart is the editor of Cleveland Magazine. He studied web and magazine writing at Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism and got his start as a Cleveland Magazine intern. His mission is to bring the storytelling, voice, beauty and quality of legacy print magazines into the digital age. He's always hungry for a great story about life in Northeast Ohio and beyond.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5