Acclaimed Cleveland Artist Michelangelo Lovelace Leaves Behind Impactful Legacy

by Ken Schneck | Aug. 13, 2021 | 12:00 PM

Courtesy Fort Gansevoort New York

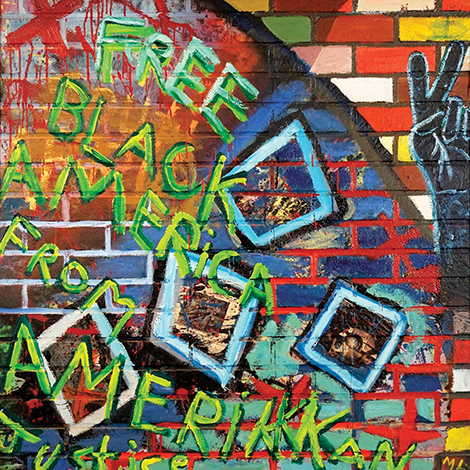

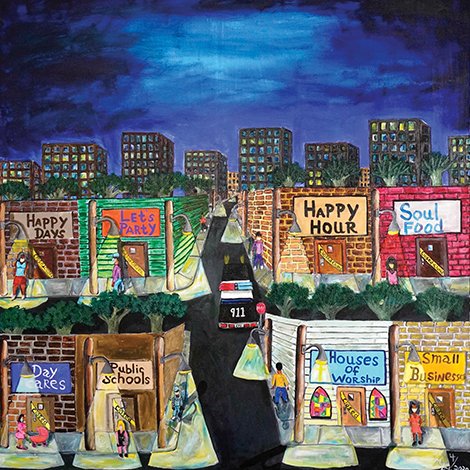

With his gritty and vibrant acrylic-on-canvas paintings depicting daily urban life in Cleveland, Michelangelo Lovelace’s art spoke volumes about a range of social issues, with one of the main themes being the disparities between the poor and the wealthy. Family and friends of Lovelace — who passed away in April at 60 from pancreatic cancer — say the artist himself was an entity far quieter than his boisterous work.

“He wasn’t a man of a whole lot of words,” remembers Shirley Lovelace, Michelangelo’s widow. “Everything he had to say, he would put in his art.”

Born and raised in Cleveland, Lovelace often told the story of being arrested as a teenager for selling marijuana and being all but mandated by the judge to pursue his passion for art as an alternative to ending up in prison. He spent the next 40 years creating art ranging from erotic drawings done in charcoal and intimate line sketches of people he encountered to his more recognizable full-color cityscape paintings — all done with the hope that he could make people pause for a moment.

“His art was his faith and he was always looking to make people feel something that made them think about life,” Shirley says.

Lovelace was honored with Cleveland accolades over the years including the prestigious Cleveland Arts Prize Mid-Career Award in 2015. In 2007, he made headlines when his piece “My Home Town” depicting a Cleveland panorama — with largely white faces on the “West Side” of the painting and Black faces on the “East Side” — was removed from the Cleveland Clinic’s main building after being accused of embracing stereotypes. The piece now hangs in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

“People would come into the gallery and say that they saw their lives and family represented in his imagery,” says Adam Tully, co-owner of the Maria Neil Art Project in the Waterloo neighborhood, which hosted Lovelace’s art at its Streetology show in 2013.

By all accounts, Lovelace had an incomparable work ethic, setting aside the time every day to work on his craft even as he worked full-time jobs in everything from maintenance to a nurse’s aide. Tully stresses that Lovelace had an innate drive to create, though his aversion to public speaking sometimes stood in the way of his work which garnered more widespread coverage.

“Michelangelo wasn’t the type to run up to a gallery owner and hype his own work,” Tully says. “He wanted his art to do the speaking for him, which it always did loudly and powerfully.”

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5