It was early in the morning, around 1 a.m., as Leo Pinkard Jr. and Denise Bradley emerged from Skeets Bar and onto East 93rd Street one day in May 2017. The pair had only just met. Pinkard, a 63-year-old vice president of manufacturing at Federal Metal in Bedford, had gone to the bar with a group of friends, says his sister Victoria Thrasher. Pinkard was always a gentleman, and true to form, he popped open his umbrella for 55-year-old Bradley as they emerged into the rain.

“He loved to dress and go out. They had a little group of guys. They’d get together and dress really nice, like an all-black affair or an all-white affair,” says Thrasher. “This one night, I guess it was an all-black affair.”

Having grown up on Benham Avenue, which intersected East 93rd Street a block south of the bar, Pinkard knew the area intimately. Another bar, Cheers, flanked the street opposite Skeets. People often left their cars parked along the curb outside it, though there were no marked parking spots, much less a crosswalk. But Bradley’s car was just across the way, and so the pair decided to brave the five-lane, 35 mile-per-hour expanse.

They had gotten about halfway across when a 2003 Chevy Tahoe barreled down East 93rd Street at what police later estimated to be 60 miles per hour, striking them with so much force that their bodies came to rest an entire block away. The Tahoe sped off, leaving a Chevy emblem and two shoes in its path. Police found the owner of the Tahoe, 36-year-old Darius Kinney, the same day. He had tried to hide the damaged SUV under a tarp. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

“It hits so close to home, and it hurts you so bad,” says Thrasher. “You see it on the TV, and it’s all you can pray about: so-and-so’s kids, they were hit and run, hit and run.”

The stretch of East 93rd Street where Pinkard and Bradley were killed is the deadliest pedestrian area in the entire city, according to Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency data. East Ninth Street through downtown takes the title of most dangerous, with 36 bike and pedestrian crashes from 2014-2018, six of which resulted in a death or serious injury. But in the same time period, 14 walkers or cyclists were involved in crashes in the roughly 20 blocks of East 93rd between Prince and Easton avenues. Ten were either seriously injured or killed. “That’s way too many,” says Thrasher. “That’s way too many deaths.”

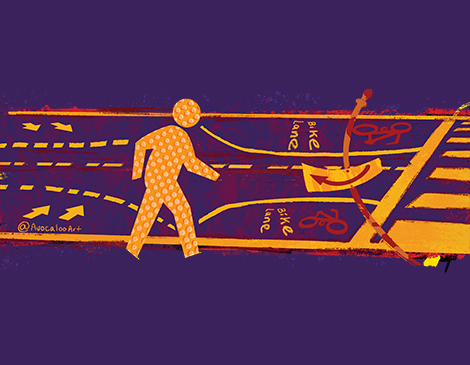

Roads such as East 93rd are exactly what Clevelander Angie Schmitt writes about in her new book, Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America. Irresponsible drivers are a significant factor in deaths and injuries, but just as important is the layout of lanes, traffic lights, medians, bollards and curbs that can slow cars down and save lives. On East 93rd Street, that infrastructure is built toward one purpose: moving the maximum number of cars through, as quickly as they can go.

The road expands from four lanes to five just north of where Bradley and Pinkard were killed, and drivers take full advantage. Traffic tends to move at 40 or 45 miles per hour. That kind of environment is particularly dangerous for pedestrians, who, when hit, take the full brunt of 2 tons of flying metal. The risk of death to a human hit by a car going less than 20 miles per hour is about 5%, writes Schmitt. But a car going 40 miles per hour will kill a person about 65% of the time. Getting hit by a car going 60 miles per hour is like falling off a 12-story building.

Yet infrastructure to slow down cars on East 93rd, protecting walkers and cyclists, is sparse. There are, luckily, sidewalks. But crosswalks are spaced far apart, and some smaller intersections have crossings on only two sides of a three- or four-way stop. Outside popular spots, such as Skeets, there are no crosswalks across five lanes. The center lane is used for turning, not a concrete median that can shield pedestrians. To cross to Bradley’s car legally and with maximum safety, she and Pinkard would have had to walk six blocks: three blocks to the intersection at Union Avenue, and three blocks back.

They were not alone in facing such a conundrum. Today about 50% more people die while walking or using a mobility device like a wheelchair in the United States than a decade ago. In 2018, more pedestrians — 6,283 — were killed in the U.S. than at any point in a generation. Low-income and elderly pedestrians are killed disproportionately, and Black men are about twice as likely to be killed while walking as white men. Distracted drivers contributed to the rising deaths, as did the designs of popular SUVs and trucks, which are deadlier than small cars. But the surest killers, Schmitt writes, are roads laid out like East 93rd: wide and fast, through areas with lots of pedestrians.

In Cleveland, those conditions are clustered in neighborhoods where resources are scarce and car ownership rates are low. About 25% of households in the city don’t have access to a car. Along that roughly 1 mile of East 93rd, there are 14 bus stops.

The road and socioeconomic conditions that contribute to pedestrian deaths still don’t get enough attention. But the overall problem of traffic deaths has reached enough of a fever pitch that Clevelanders are beginning to do something about it. In 2017, then-councilmember Matt Zone convened Vision Zero, a local task force that branched out of the international Vision Zero movement. It united nine organizations around the goal of bringing the 37 or so traffic deaths in the city every year (including pedestrians) to zero.

The task force has made slow but steady progress, including an in-depth study of the city’s “high injury” roadways. Most, like East 93rd Street, are scattered on the East Side, including super-wide East 55th Street, Superior Avenue east of East 55th Street, where the bike lanes leading out of downtown end, and virtually all of Kinsman Road.

“You can look at the high injury network, and you can overlay that with a redlining map, or you can overlay that with infant mortality rates,” says Bike Cleveland’s Jacob VanSickle, co-chair of Vision Zero’s data evaluation subcommittee. “Every map you look at that isn’t good, it is going to be the same.”

All that data-crunching is finally beginning to crystallize into policy. Councilmember Kerry McCormack worked with the Vision Zero task force to introduce a complete and green streets ordinance into City Council in August, which would beef up the city’s existing law. And the city has hired consultants to gather community input and make a Vision Zero action plan this fall, with the eventual goal of making roads safer for everyone.

But the obstacles to roads that look more like Euclid Avenue in Midtown and less like freeways are significant. Ohio sets speed limits at the state level, and Cleveland has scant resources for road improvements, which the city has directed toward repaving the worst-condition roads first. Barring changes in city policy, dangerous but good-condition roads like East 93rd Street might not get lifesaving changes until they are cratered with potholes.

More light is being shined on the issue of pedestrian safety than ever before, however. Bike Cleveland is even planning to spin off a local chapter of Families for Safe Streets, a national victim support and advocacy group, by spring 2021.

Thrasher has been looking for an organization like that. After her brother was killed, she received a call from a family member of another person who died in a crash, but she wasn’t sure where to turn. Now, she says, she’s ready to start speaking out.

“More than anything, I need people to know that these statistics are a life,” says Thrasher. “They are a life.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=d67cfd8c_1&w=640&auto=compress%2cformat)