Community Bonds

Eleven years ago, Peggy Kennell moved to Judson Manor with her husband, John, and immediately found a community. “That’s very important when you don’t have family in town,” says Kennell, whose husband passed away in 2013 and three children live out of state.

At 94, the active go-getter serves on the Judson welcoming committee, oversees the 70-plus plants in the building’s penthouse and gets her hands dirty in the rooftop gardens. She even works every other week at the Manor Mart shop that provides convenience items to residents.

“She is really an inspiration,” says Regina Staple, a nurse navigator at Judson who builds relationships with residents and assists with everything from care arrangements to moral support. Her work goes deeper than typical case management — Staple serves as a surrogate family member for many.

That was certainly the case for Kennell when she unexpectedly fell in fall 2017. While standing by the elevator getting ready to head to dinner, she decided to go back to her apartment to get something. “I turned quickly, lost my balance and fell,” Kennell says.

While Kennell did not break her hip, the twist and tumble caused severe injury. A friend drove her to University Hospitals for emergency care, but not long after, Staple arrived to check on her.

“She came early the next day,” Kennell recalls, adding that Staple “was so understanding and supportive in many ways.”

Staple reached out to Kennell’s family and communicated with the nurses and doctors. A former pediatric nurse, Kennell has a strong mind about quality care. In fact, her husband, Dr. John H. Kennell, known as the “bonding man,” created the doula process and conducted research on babies’ need to be with their mothers after birth, not isolated in nurseries.

The Kennells moved to Cleveland in 1952, when John was recruited from Boston Children’s Hospital to help start the medical curriculum at what was then Western Reserve University.

“We were very fortunate,” Kennell reflects. “We traveled a lot.”

Getting to know people like Kennell is part of what makes Staple’s job so special, she says. “As a navigator, I’m an advocate and a liaison,” Staple explains.

As one of her duties, Staple performs home assessments before potential residents decide to move to Judson. “Once they move in,” she says, “I make visits to get them situated and start building a relationship.”

Staple identifies whether residents require physical therapy or a home health aide. And, as in Kennell’s case, she helps the care process go smoothly when the unexpected happens.

Staple was alongside Kennell during her transition from the hospital to Judson Health Center, where Staple continued to visit and update Kennell’s family.

“She just cheered me up,” Kennell says. “It was so reassuring.”

Within a couple of weeks of her fall, Kennell was back in her independent-living apartment. “I made sure she had everything in place to be safe and to recover,” Staple relates.

Having a nurse navigator who has taken the time to get to know her is very important to Kennell and her family. “We’re very fortunate to have services like this at Judson,” she says.

Kennell returned to her usual activity after about a month — tending to the plants, greeting residents who visit Manor Mart and continuing her role on the welcome committee.

“Aging is all in how you approach it,” she says.

Expanding Horizons

It was supposed to be a day filled with joy.

But just after giving birth to her son, Jaxxon, in 2012, Akron resident Nina Ledbetter received some upsetting news. Something was very wrong with her new baby. The staff immediately whisked him away, sending Jaxxon and Ledbetter’s husband, James, to Akron Children’s Hospital for a diagnosis.

“The description that my husband gave me was that the doctors’ jaws dropped when they saw Jaxxon’s X-rays,” says Ledbetter.

The X-rays showed significant deformities in his rib cage and spine. Puzzled, the staff told Ledbetter her son likely wouldn’t survive and offered to begin comfort care. “I told them that that wasn’t an option,” she says.

Leaving Jaxxon in the neonatal intensive care unit, Ledbetter got to work. “All I had was a picture of his X-ray, so I got on the internet and I did not stop looking until I saw another child’s picture of their skeleton that matched up as similar as possible to my son’s,” she says. “That’s when I found the condition: Jarcho-Levin Syndrome.”

The rare, genetic disorder causes malformation of the ribs and the vertebral column. As children with JLS grow, their ribs do not grow with them, constraining the lungs and causing breathing problems that often prove fatal. Yet, Ledbetter was undeterred.

She started researching treatments, finding a procedure at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio that involved implanting expandable titanium ribs. At less than a year old, Jaxxon was flown to the hospital in Texas via private medical jet. The doctors fitted him with a set of vertical expandable prosthetic titanium ribs, but the procedure required Jaxxon to be flown there twice a year to have the ribs surgically adjusted to accommodate his growth. The travel costs added up fast, and Ledbetter began looking for a surgeon closer to home.

Her search led to a new doctor right in her own backyard: Dr. Justin Mistovich, an orthopedic surgeon at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital. Mistovich had trained with Dr. Robert Campbell, the creator of the VEPTR. His qualifications and friendly demeanor quickly impressed the Ledbetters.

“He just seemed like he cared a whole lot,” says Ledbetter. “We still believe that to this day.”

Now 6-years-old, Jaxxon still has to get his rib implant adjusted about every six months, a process which involves surgery to move a peg to the appropriate setting for his current size.

“If you want to think of it in mechanic’s terms, it’s almost like a car jack for his chest,” says Mistovich.

And it’s working. Once completely dependent on a ventilator, Jaxxon is now able to be without it for periods of time. The first-grader is running, playing and learning to read just like his peers. The ultimate goal is for him to live a normal life once fully grown.

“It’s been really fun watching Jaxxon grow physically and get bigger, which is impressive in and of itself,” says Mistovich. “It’s also been amazing to watch him develop and become the little young man that he is today.”

They say it takes a village to raise a child. According to Mistovich, it takes one to heal a child too. “All these players have to be engaged in building a community of care that can help tailor custom solutions for kids with these rare diseases,” he says.

While the constant care and frequent hospital visits can take a toll, Ledbetter feels fortunate that her son, once predicted to die, seems to have a bright future.

“I cannot say that it isn’t stressful, but Jaxxon makes everything worthwhile,” she says. “His position on life is just so happy, beautiful and sweet.”

Setting the Pace

On the first Sunday in November, Steven Youngkin finished the New York City Marathon.

At age 49, he typically runs about six miles a day. But just a few years ago, he would have laughed out loud if anyone suggested he could finish a 26.2-mile race. In 2015, the Cuyahoga Falls resident tipped the scale at 421 pounds.

“I had gained weight on an annual basis since my late 20s,” he says. “I realized, OK, I need to do something about this.”

It’s not that Youngkin had ignored his growing size. “I tried Weight Watchers. I tried Nutrisystem and the Atkins low-carb diet,” he says. “I’d lose 20 pounds, then regain 25. Lose 15 pounds, then regain 20. I needed something more permanent.”

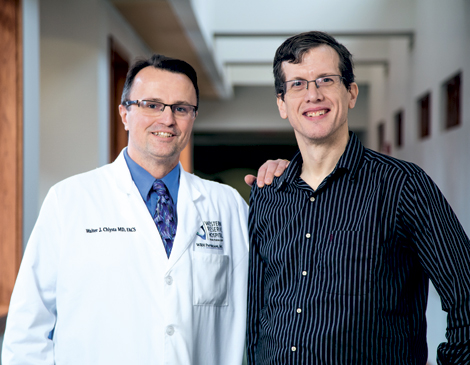

So he met with Dr. Walter J. Chlysta of Western Reserve Hospital to discuss bariatric surgery.

“Our patients take a big step by coming in to see us and start the process,” says Tonya Thomas, nurse practitioner at Western Reserve. “A lot of them are ashamed about needing help to lose weight.”

But Youngkin realized from the get-go that bariatric surgery is not a cure. “You have to be willing to commit to eating better and exercising to keep the weight off,” Youngkin says. “There’s only so much that a surgery can do.”

Before the surgery, Youngkin says, his typical breakfast consisted of a large bowl of cereal, followed by big glasses of orange juice and milk. Then, he’d eat a Pop-Tart, followed by two doughnuts. He wore size 6-XL T-shirts and pants with a 62-inch waist.

“Now, I have an English muffin and a smaller cup of orange juice,” he says. “My cereal bowl is half the size.”

Today, he wears a medium T-shirt and his pants dropped to a size 34. “This is a long-term venture,” Youngkin says.

He had been suffering from chronic back pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, sleep apnea and high blood pressure. With a body mass index between 35 and 40 and related health problems, Youngkin was a good candidate for bariatric surgery, Chlysta says.

He performed a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, which involves “stomach stapling” to divide the stomach into a large portion and smaller one that can hold about a cup of food. This small pouch is disconnected from the main stomach and connected to a part of the small intestine. Food is basically routed to this pouch, which by nature of its size, restricts the amount a person can eat.

“It limits large meals and also decreases your hunger over a period of time, usually a year,” Chlysta explains.

In addition, most doctors recommend 30 to 40 minutes of exercise several days a week. Surgery is considered a success if a patient loses more than 50 percent of excess weight a year after surgery.

Youngkin hit the starting line running. Before his surgery on Oct. 5, 2016, Youngkin got his weight down to 348 pounds by walking and watching his food intake. This helped him drop about 2 pounds a week. He started a Couch to 5K program. In the beginning, he could only walk about a quarter-mile before getting worn out. By surgery, he was walk-running a few miles.

“I wanted to get myself tuned in to exercising every day and eating better so it wouldn’t be such a culture shock after the surgery,” he says.

Seven months after his surgery, he had reached his goal weight of 221 pounds. A year post-surgery, he had lost 110 percent of his excess body weight and began considering the marathon he’d run in November 2018.

Today, Youngkin weighs in at 181 pounds. “I feel more confident,” he says, adding that he doesn’t have to ask for a seat belt extender when he flies for work (he’s a computer consultant), and he can shop for clothes in any store he wants.

Youngkin has plans to run other marathons this year, and all of the related health issues have disappeared. He emphasizes the point that his surgery was a tool — the hard work is on him.

“If you buy a screwdriver at Home Depot and use the wrong end of it, it won’t work,” he says. “It’s not the fault of the tool — it’s your fault for not using the tool correctly. If I don’t use the surgery correctly and go back to my old habits, I’ll gain weight. The surgery can provide you the means to achieve weight loss, but you have to go the rest of the way.”