If I were Hemingway, and who wants to be, I would say that there is a smell of death hanging around this mayoral election. Not physical death. Nothing that sensational. Spiritual death is more like it. Dull death.

You got that feeling from the very beginning as you watched the potential candidates tap dance in and out of the spotlight — announcing their candidacies one day/withdrawing the next. Making bids tentatively, then snatching their cards back off the table like spinsters playing rummy.

There was an obvious message in that. The message wasn’t in the speeches but when is it ever? The message was in the frenzy — the indecision. And the message was that the job of mayor of Cleveland has become a rotten job. Nobody wants it for itself.

George Voinovich, it is said, would hardly have entered this race if he hadn’t run into some sort of roadblock on his way to the Governor’s Mansion. But he found obstacles in his road, and it was necessary to take some sort of detour. A detour that would keep him moving in generally the right direction on a bad and muddy road. The kind of road where you have to worry about breaking an axle.

Ed Feighan, before illness intervened, obviously had sincere doubts that the mayor’s job was worth applying for. He wanted to but didn’t want to — like a good little girl parked in the woods with the high school stud who anguishes over her choices until she finally throws up and that settles matters.

And then ... as ever ... there is Dennis. Dennis, of course, already has the job. But there is the problem of getting rid of it under the right set of conditions. It’s a little like the real estate market these days. Most people figure it’s smart to hold onto the houses they have — even houses where the basement leaks and there are piranha fish in the water. Better to hang onto such a house than give it up and try to find a place you can afford in today’s market.

So Dennis clings to City Hall. And in Washington, aides to Senator John Glenn nervously wonder when the day will come when he might try for the Senate. That day is not yet. Dennis isn’t ready yet. He still needs a political address, and Lakeside Avenue is the best around.

All of this is interesting to people who enjoy the sport of politics — people from Parma, say, or North Royalton, or Scottsdale, Arizona. This town is a barrel of fun for such people who don’t live here and never would. A whole group of political hobbyists enjoy following the sportive events that transpire here. I really think there ought to be a magazine for them — a kind of cross between Runner’s World and Strength and Health.

If, however, you take the view that the purpose of city government is to govern cities, then there is the smell of death around this mayoral election. For there is a very real question whether this city can be governed at all.

Not long ago, I chatted with Carl Stokes about Cleveland. I wanted to get his views as an ex-mayor about the craft of mayoring here. I didn’t want to get into personalities, but he mentioned Dennis and discussed him with a good deal of compassion — startling to anyone who remembers the fights the two of them used to have a thousand years ago last decade.

“Dennis has merely inherited a set of problems that are built into the system in Cleveland,” Stokes said. “The two biggest problems are the size of city council and the length of term for the mayor. And they are related.

“The size of city council creates a situation where the councilmen, in their scramble to hold onto small constituencies, fail to concentrate on the big, overall problems of the city. They are constantly jockeying for political advantage.

“The mayor has to worry about this and he also has to worry about getting re-elected. No sooner is he sworn into office than he has to think ahead to the next election and weigh his actions in the light of what is to his political advantage. As long as these conditions exist, the city will not be able to move toward solving its problems.”

I think that analysis is absolutely right as far as it goes. But it doesn’t go the whole way. Industry is leaving town or threatening to. People are moving away, and the chaos in the school system will drive more of them out — and keep outsiders from wanting to move in if there are any left who might consider it.

Euclid Avenue is beginning to look like Prospect did 20 years ago. The outward face of the city is beginning to show the results of dissipation. The question is becoming not so much who will govern as what is there to govern?

This election won’t solve any of these things. It isn’t really about that. It’s really about a couple of guys looking for a room to rent until they find another place to live.

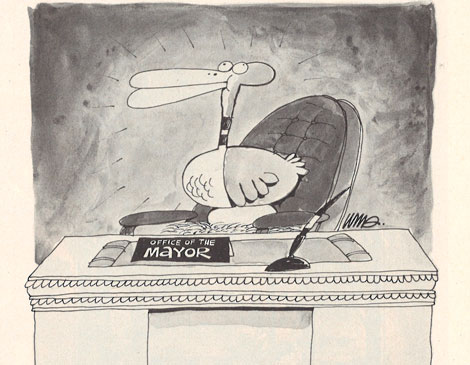

City Hall is their hotel. A musty old hotel with an unpleasant odor to it. The odor comes from outside. It is the sickroom smell of the city, and you shake your head and you wonder how long it can hold on.

This story originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's October 1979 issue.