Dear Mr. President

Samantha Schaedler mailed a letter to Donald Trump on Inauguration Day. Every day after, she sent another, driven by her belief in our political system.

Story by Sheehan Hannan

Monday, May 07, 2018

Samantha Schaedler mailed a letter to Donald Trump on Inauguration Day. Every day after, she sent another, driven by her belief in our political system.

Story by Sheehan Hannan

Monday, May 07, 2018

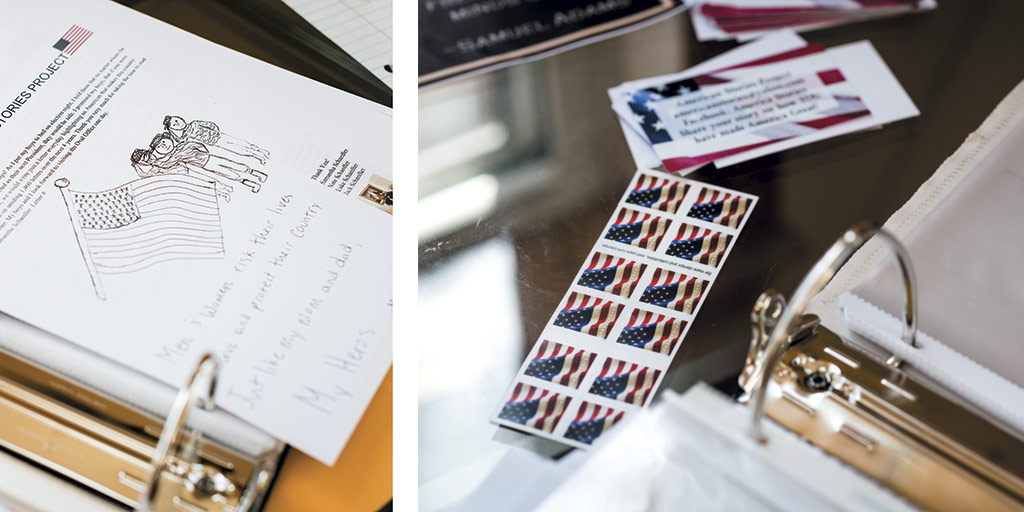

Samantha Schaedler cracks open a massive three-ring binder. Inside, protected by plastic, are 145 copies of more than 450 letters on identical stationery sent to “Mr. President.” Each one gets a U.S. flag stamp in the right corner of its envelope and a red, white and blue American Stories Project mailing label in the left before being sent off to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Washington, D.C., 20500.

A teacher for more than 20 years, she lays the binder on her couch and flips through the pages like it’s part of a lesson in her American history class. On the front cover, bold letters proclaim the simple rules each letter must follow: “Is it kind? Is it true? Is it positive?”

She pages past a letter she wrote about her husband, Rich, and ones her sons wrote about Jackie Robinson and Abraham Lincoln.

She stops on a page filled with cramped, neat handwriting. A woman wrote about her great-grandmother, Goldie Glanz, who came through Ellis Island from Lithuania at age 12 and found hope and opportunity in the United States.

“It wasn’t about where you were from, your background or your political ideology. It’s just about working hard,” Schaedler says. “Words to live by.”

A few of her friends’ young children scribbled pictures in marker of a smiling police officer wearing a red shirt and blue hat and a green fireman driving a futuristic truck with towering red and blue lights on top.

Then she turns to one of four form letters she has received from the White House. “He actually signed it,” Jack, her 9-year-old, exclaims, pointing.

“No, not that one,” his mom says. “The one he actually signed is framed. You want to go get it?”

Jack dashes away, his mismatched socks sliding on the wood floors of their Bainbridge Township home, and returns with the letter. It is written just for them, printed on White House letterhead and addressed to “The Schaedler Family.”

Jack hands it to his mom. At the bottom, in a jutting, angular hand: “Donald J. Trump.”

“We put it on the kitchen counter, and I look over and there’s a piece of fried chicken sitting there,” Schaedler laughs. Luckily, they avoided any stains. “I’m like, ‘Boys, boys, we got to do something.’ So we framed it.”

“As your President, it is my goal to cultivate a land of freedom and opportunity, where the American Dream is very much alive and attainable,” President Trump wrote. “Though we may differ at times, we are always united by our Nation’s founding principles, our commitment to democracy, and the strength of the American spirit.”

That’s exactly why Schaedler began sending the letters in the first place. She loves this country’s democratic system and the 49-year-old works hard at it.

An avid reader of history, she’s currently engrossed in a biography of Booker T. Washington, the former slave and iconic educator who founded the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. She volunteers at the USS Cod Submarine Memorial moored in North Coast Harbor. She is a registered Republican, a Daughter of the American Revolution and a concealed carry permit holder.

In her eighth-grade classroom at Orange’s Ballard Brady Middle School, she teaches students about the Founding Fathers, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Every year, she organizes the school’s Veterans Day program.

“This is my life, this is my passion,” she says. “This is what I believe in.”

But the presidential campaign and election of 2016 challenged her faith.

“The political rhetoric was so negative on both sides,” Schaedler says. “It was really hard to explain to the kids what was happening and why these things were happening.”

One day during the campaign, Schaedler was driving her boys Nate, Luke and Jack to one of their numerous sports practices in her SUV. Between basketball, baseball and soccer, one car ride blends into another.

Then a story crackled on the radio.

Although presented in the mellow tones of an NPR report, it upset her so thoroughly that she remembers it even now. At a campaign rally in South Carolina, Trump mocked a disabled reporter from The New York Times, flailing his arms in a crude imitation.

Many of her friends work with disabled or developmentally challenged students. One boy she teaches is visually impaired. He puts his face inches from his computer screen to see the words. But she has seen him learn and grow. He plays the piano beautifully.

So, as she looked in the rearview mirror at her boys, she was dismayed by Trump’s actions. “I support the Constitution. I support the process,” Schaedler says, “I support the whole process and I just felt like, How do I explain this to the kids?”

She worried they might get the wrong message — that politics is all nastiness, that Americans cannot disagree amicably, that the whole system might be a showman’s shtick, a sham. What kind of system could foster a man who said such things?

An idea blossomed in Schaedler’s mind that day. “Oh my gosh, we have to do something,” she said to them. She promised her boys that if Trump was elected, they would write him letters as a statement of faith in the goodness of American democracy.

She didn’t think much about it until months later on election night when news outlets began reporting that Trump would become the 45th president of the United States.

Before the Schaedler boys headed upstairs to their rooms, Jack reminded his mother of the promise.

“As I put my boys to bed on election night, I told them that no matter whom the American people elected as their next President, they would be safe,” Schaedler jotted down on the paper that would become her letterhead. “I promised my boys, that if you were elected President, we would write you a letter everyday highlighting an American that makes this country great.”

“This is my way to share my love for the country,” Schaedler says, “my belief in what our Founding Fathers put forth in the principles of the country.”

My dad was not a war hero or a successful business man. My father would never miss a day of work, was a man of his word, fought in a war and would never forget to vote. Just being a good citizen day in and day out makes a person like my dad an unsung hero. — Anonymous, Letter No. 50

The day after the election, Schaedler returned to her classroom not quite sure what to expect.

For the self-proclaimed “history nerd,” the 30-by-30-foot room with its four-desk pods is her oasis. In one corner, a large white plush-toy bill, like the one from Schoolhouse Rock, perches atop a filing cabinet. A paper-mache model of Lincoln anchors another corner.

A few of the ceiling tiles are painted with scenes of the U.S. Capitol, the Lincoln Memorial and the White House, while a “Don’t Tread on Me” flag hangs over her desk.

A photograph of Schaedler as an eighth-grader at Chagrin Falls’ Kenston Middle School hangs on the wall. Surrounded by her classmates, Schaedler beams as she stands in a middle row with the dome of the Capitol jutting into the sky behind.

The former Washington, D.C., tour guide organizes the same trip for each of her eighth-grade classes. And every year, Schaedler makes the students line up to take a similar portrait. Laminated pictures dating back to the 1990s fill the space above her white board.

So before the first bell rang on Nov. 9, Schaedler talked with a few colleagues. They knew the students would have questions. What could they say? No one seemed to know.

As a public school teacher, Schaedler presents historical facts but also challenges her teenage students to ask questions, probe deeper and think critically. Given the divisiveness of the election, she had tried to keep discussion of the electoral system out of her classroom. But today, avoiding it would be impossible.

Like many of her students, Schaedler’s feelings were complicated. Her mother, also a teacher, lives in the house next to her and had voted for Trump. So had her husband, Rich. In Geauga County, 60 percent of voters did too.

Schaedler’s party affiliation and background might suggest that she would as well. For the whole year, Trump was hard to avoid, even coming to Cleveland for the Republican National Convention. But that video of him with his arms distorted and flailing kept popping into Schaedler’s head.

“I tried so hard not to emphasize how negative it was,” Schaedler says. “But it was there. There wasn’t much I could do, other than tell [the boys] it was going to be fine.”

Schaedler respects why someone might vote for Trump. Her family is from Southeastern Ohio, where coal and its legacy weigh heavy. Coal dust is in her bloodline. When Trump said he would revive the industry, Schaedler could understand how her family, and people like them, might believe him.

“But listening to what he said, though, too often it was too hard to explain to my kids,” Schaedler says. “I think that’s why I had to draw the line.”

So Schaedler voted for Hillary Clinton.

On the day after the election, one of Schaedler’s students, an African-American girl, came to her classroom at the beginning of class. “Ms. Schaedler, what are we going to do?” she cried. Schaedler had no answer. The protective barrier of the classroom dissolved with her student’s tears, and she cried too.

“I don’t know, it’s going to be fine, it’ll be OK,” Schaedler told her. “’Cause it will be, it will be fine. It’s the democratic process, and we should celebrate the democratic process.”

America has always been a country of everyday heroes. A country where people rise up from adversity and come together for a greater good. It has always consisted of great people doing great things. Like everything else, it will never be perfect. But, I still believe it’s great. Saying we need to make it great again implies otherwise. I’m not sure that’s accurate or fair. — Anonymous, Letter No. 57

A few weeks after the election, the school principal called Schaedler to his office. He had heard about her plans for the letters. Parents and students might see it as a hint of partisanship creeping in, even though that’s not what Schaedler intended. So they agreed that her class would not write letters.

“I’m a little leery about presenting it to my students, because I don’t want them to go home and be like, Ms. Schaedler made us write a letter,” she says. “As an eighth-grader, that’s what you’re thinking.”

Democracy isn’t easy.

One of Schaedler’s favorite topics to teach is George Washington’s farewell address. Delivered in 1796 as he was leaving office, Washington warned of the formation of political parties and how excessive partisanship can lead to animosity and division. “To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a government for the whole is indispensable,” Washington said.

But Schaedler also knows that, just as often as the nation has strived for Washington’s ideal, disagreement has been a feature of the American system.

Schaedler follows up that lesson with the election of 1800, when the nation was thrown into a nasty, partisan election. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams duked it out, brutally, with competing newspapers and ugly invectives.

She knows that Washington’s farewell address and the election of 1800 are equal parts of our history. But she also strongly believes that even people who disagree can celebrate the same values. So she strives for empathy and understanding, a space we can all share.

“I’m afraid we don’t even take the time to listen,” she says. “It’s all about listening.”

So Schaedler made her stationery, and bought her binder, envelopes and stamps. On Jan. 20, she sent her first letter. She wrote about a family friend, Bob Jackson. He had died in December 2016, from fibrosis of the lungs.

Jackson led a hard life. In his childhood, he rotated in and out of the foster care system and orphanages, where he had an accident that cost him his eye. For the rest of his life, he had a glass prosthetic.

But Jackson did not grow bitter. He was funny and smart — a talented artist, a voracious reader and a vigorous debater. After so much hardship, Jackson became a wonderful father and a caring partner to his wife, Lisa, and their children.

“He grew up in an orphanage, worked hard and achieved the [sic] what most would describe as The American Dream,” Schaedler wrote.

For the second letter, she wrote about her husband, Rich. Politically, they disagreed. But she saw in him the kind of role model she hopes her three boys will grow up to be.

“When our 10 year old did not make the travel baseball team, he told him that he was proud of him, that he has great potential (Luke is a leftie) and shared the story of Michael Jordan not making his basketball team,” Schaedler wrote. “He then created a baseball team for all of the kids that did not make the travel team.”

Jack, Nate and Luke Schaedler have all written letters to President Donald Trump.

While her mother and husband haven’t written a letter, Schaedler’s boys have been penning wildly, writing about presidents and pioneers.

Jack wrote about Los Angeles Dodgers great Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in the major leagues. “People were mad that he played but he was strong. He made America and baseball great.”

The boys’ friends wanted to write letters, then their parents. The kids who were too young to write simply drew pictures. The letters began to flow in a torrent after the Chagrin Valley Times and WKYC covered Schaedler’s project.

She set up an email inbox, americanstories@yahoo.com. Letters stream into it from Clevelanders, ex-pats and relatives throughout the country.

Lee McClain, a seventh-grade language arts teacher at Schaedler’s school, sent in a letter — No. 230 — about Joe Paris, another teacher at Ballard Brady. It was a nomination letter for a Kiwanis award, but Schaedler sent it along anyway.

“It’s so clear that his students love him, that he is an effective educator, and that he is a born teacher,” McClain wrote. “This is the kind of teacher I long to be.”

Ursula Apaestegui, a woman from Stow, sent in a letter about her father, Julius Batu. A Hungarian immigrant, he came to the United States in 1956 with no money and only the clothes he was wearing. He enlisted in the Army and, after serving his adopted country, worked his way up from cleaning in a bakery to supervising supermarket bakeries to owning a bakery of his own.

“To this day my father continues to talk to my brother and me about the great opportunities there are in the U.S.,” Apaestegui wrote in letter No. 302. “He often begins with, ‘Only in America…’ ”

“It started out as just a simple way to say, ‘Hey, we are great’ and ‘We’re gonna be OK,’ ” says Schaedler.

There was a lot of fear in the election, she says. People were scared, of each other, of outsiders. For her, reading and writing the letters was a salve, a way to soothe some of that fear.

That first letter can be empowering. “It is a moment where you’re like, Wow, it can be so much more than a letter you are sending to the president,” says Schaedler. “Because you can reflect on where you are in life and what’s going on.”

Jack’s third-grade teachers at Timmons Elementary School took a fistful of letterhead and assigned their students to write. The kids weren’t experts at spelling or grammar, but they didn’t need to be. Their assignment was to chronicle whoever inspired them — parents, grandparents, brothers, friends.

Dylan Gibb, a third grader, wrote to Trump in letter No. 369: “I love you as a President. You saye very good things abowt are world and are century.”

Another student wrote about his friend Gavin. “Gavin is a positive friend of mine (well known) he helped me when we were partners. Gavin is my best friend. Scincerely, Sir James.”

Their classmate Sedona wrote about Olympian Simone Biles. “She is 4 foot 9 and petite. She is small, just like me. … Her birthday is on the same day as mine. Simon’s birthday is March 14th. And that is why Simone Biles insirs me.”

Schaedler’s friends tell her that she is inspiring — that what she is doing can change lives. But sometimes, Schaedler despairs. The news seems to say Americans are more divided than ever. It floods in every day, wave after wave, forming a noxious ocean.

“Wouldn’t you like to say, ‘Yes, this is really impacting the world?’ ” she says. “But it’s not.”

She perseveres anyway. She looks for the best. “It’s a way for people to feel better about what’s happening and not feel so helpless — or hopeless. Maybe it’s a way not to feel hopeless,” she says.

Every day, she picks a story and licks a stamp.

She recently received another letter from the White House, with a list of great things that President Trump has done for the country.

Her letter carrier, who now recognizes the letters on sight, brought it all the way up her long driveway to hand-deliver it. “We opened it and just giggled,” she says.

“Maybe they’re rolling their eyes at us and are like, ‘Oh my gosh, she’s sending another letter,’ ” says Schaedler. “They’ll have a pile, it’ll just keep growing — an American Stories Project pile of letters that will just keep growing.”

Some will tell stories of people who praise the president and his values. Others will tell stories of those who protest. Still others will fall somewhere in between.

But Schaedler will send them all. To her, that makes America great. “The system works,” Schaedler says. “It works perfectly, even if we don’t agree.”