It was a loving request made with the volume of a scolding, but I’d close the pages reluctantly. Each book was a shield for me against what I couldn’t control or countenance about this world.

At first, books were tethered to my mother’s love. Her voice provided my first experience of voice-over, as the words organized the chaos of images.

Her lap’s warmth, her body leaning close, enveloping me. Goodnight Moon, its uncannily quiet bedroom scene. Green Eggs and Ham, Dr. Seuss’s rollicking rhymes. We read the same books until I could recite them by heart.

On many occasions after dinner, my father would snuggle on the bed between my sister and me, open our book and drift off to sleep. Even our proddings couldn’t wake him. We’d finally call out to Mom, “He’s asleep again!”

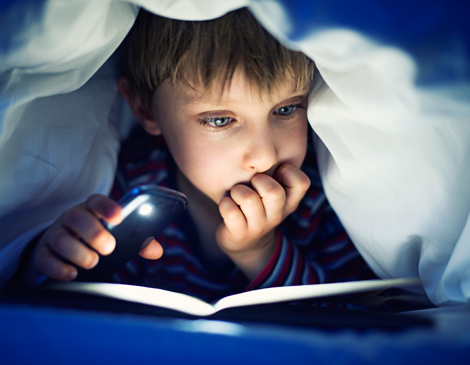

Years passed. Those black marks on the page suddenly revealed their secret meanings. Now I could conduct solo journeys into my imagination. I read into the night, musty Hardy Boys adventures in hardback inherited from my uncle, Eric.

Every time I opened a new one, I recalled the model airplanes that still hung in his long-abandoned bedroom. I would hurry toward every book’s ending like a starving person gorging on whatever was edible.

I must have been about 12 when I bumped into J.R.R. Tolkien. A friend of my parents gave me a worn paperback of The Fellowship of the Ring, and I was promptly lost in the Misty Mountains. Tolkien was a literary version of George Lucas — he created an entire world, with its own history, revealed in every encounter had by the humble hobbits Bilbo and Frodo.

After reading the delightful The Hobbit, I discovered something beyond my youthful worldview in The Lord of the Rings.

It felt noble and grown-up, as the characters wrestled the dark realities: toxic addictiveness of power, the destructiveness of human desire and the twilight of the age of magic. It was like the difference between The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. You had to grow up to leap between them.

Somewhere along the way, there was a wardrobe. Rather, the wardrobe, where Lucy scurries to hide from her siblings and winds up in Narnia.

The wardrobe is one of the great metaphors of reading itself. We enter it and find ourselves in another world. C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia was as delicious in its own way as Tolkien. I loved the sense that time passed differently in this other world, as it did for me while reading.

I could have been lost in Narnia for hours, but it seemed as if it were days or even years. Reading the books to my daughters, years later, I couldn’t stomach the Orientalism of The Horse and His Boy. I held my nose at the stench of misogyny around the witches and women.

But as I reached the ending of the final book — The Last Battle, when the main characters find themselves walking into the paradise of afterlife — waves of emotion overtook me.

After C.S. Lewis came mountains of fantasy imitators. Quite simply anything with a dragon or a dwarf on the cover drew my eye, fueling my fantasies for the authorial role-playing of Dungeons & Dragons. That game was like creating our own books in the air between our brains, imagining the caves and forests where our characters used cunning, courage and creativity to defeat monsters of our own making.

Reading was, and is, magic to me. How else to describe how inked letters yield whole worlds and plant them in my head, populating my dreams and haunting my days? I wanted to know how to make such magic.

In high school, my fantasy reading yielded to the classics. The dragons were now inside me. The veil of magic had evaporated, and the adult world cast down its harsh light. I read Malcolm X and Juan Rulfo and Graham Greene and Alexandre Dumas and Jane Austen and Albert Camus and J.D. Salinger. The world seemed fraught with complications, injustice, cruelty and difficult choices.

I spent 30 solid years reading everything else, even works I disliked, just to stretch out my inner horizons.

But these days, I am far choosier. I have grown impatient with posturing, mind games and dry erudition. When I decide on a book now, one just for me, I’m looking to get to the heart of the matter. I want both the magic and the real. To enter a dream of life, to wake up to this one.

Even when it’s cement gray outside, as it is most winter mornings here in Cleveland, with only the hint of light in the sky, I want to cherish this awakening. So when I see my daughters plugged into their phones, gazing at screens, my loving and grouchy father rears up in me. I badger them, another dad at breakfast. “Hey, give those things a rest. Talk to me!”

But when they are reading a book, enveloped in another world, I close the door or tiptoe delicately past, not wanting to break the spell.

Except at dinner, when the gray outside has turned to dark again, and I ask them to close the books and open up the story of their day.