For many years, near East 105th Street and Ashbury Avenue, there stood a cottonwood tree. It grew and grew and grew, close to the back wall of an art deco-style gas station until, with its offspring, it made the boarded-up building a piddly little thing, swallowed by a puddle of mighty shade. When the wind swished, the oval leaves conjured the rain.

Then the men in hard hats came in their pickups, with their blueprints and notions of progress and cut the tree down. Their backhoes toppled the gas station and churned the urban farm next door, until where the tree rooted was blank. And the hard-hatted men could begin again.

Julie Ezelle-Patton watches them from the dining room table of her third-floor Glenville apartment. A poet, she wears a roughly sewn blue sweater and an orange and blue head wrap that makes her appear at least 6 inches taller.

We spoon at oatmeal, served by building manager Arcey Harton, and sip lapsang tea from earthenware cups as the workers stomp about on a muddy lot bordered in chain-link fences.

For months, the lot behind Julie’s apartment block has been a buzzing hive as a four-story complex of 63 apartments and storefront retail rises. Expected to be complete this spring, Circle North extends for almost an entire city block.

To Julie, it is a blinking danger sign. She grew up in this part of Glenville. She dropped off papers for her brother’s Plain Dealer route along East Boulevard and spent evenings collecting leaves and watching baseball games at Gordon Park.

She honed her poetry with students of Russell Atkins, trading verses on the porches of Olivet Avenue, while her mother painted in the kitchen inside.

Julie channels that community memory into her art, layering new work onto the old, drawing materials and inspiration from her family, the trees, the buildings. Now that world could change in ways she doesn’t recognize, through the wrecking ball, the excavator and the crane.

But Julie does not fear just for herself. For years, she has tended and lived inside one of the Cleveland art world’s best-kept secrets, a haven for artists, musicians, poets and Bohemians.

Outside, it is camouflaged, one of 12 red brick structures along East Boulevard, across the street from the jogging paths and rustling treetops of Rockefeller Park. Its entryway is like so many others on the East Side, a simple number perched atop a concrete prewar arch.

But inside, the eight apartments have hosted a miniature Harlem Renaissance. Since Julie bought shares in an apartment there in 1987, she has maintained the building as an ongoing art project. Part residence, part community center, part arts incubator, it morphs and re-forms, harmonizing with the artistic needs of whomever has taken up residence.

“This is University Circle, squared,” Julie says. “We have music, we have natural history, we have a botanical garden, we have art and we have history going back to the 19th century.”

Dozens of creative people, in the rising action or denouement of their careers, have passed through its walls: RA Washington, Daniel Gray-Kontar, Marjorie Witt-Johnson and Nina Sarnelle. They slept on its couches and held salons in its living rooms, grew food in its garden and hung paintings in its basement.

“We’re basically caretakers of these legacies, with the hope of keeping them safe,” Julie says.

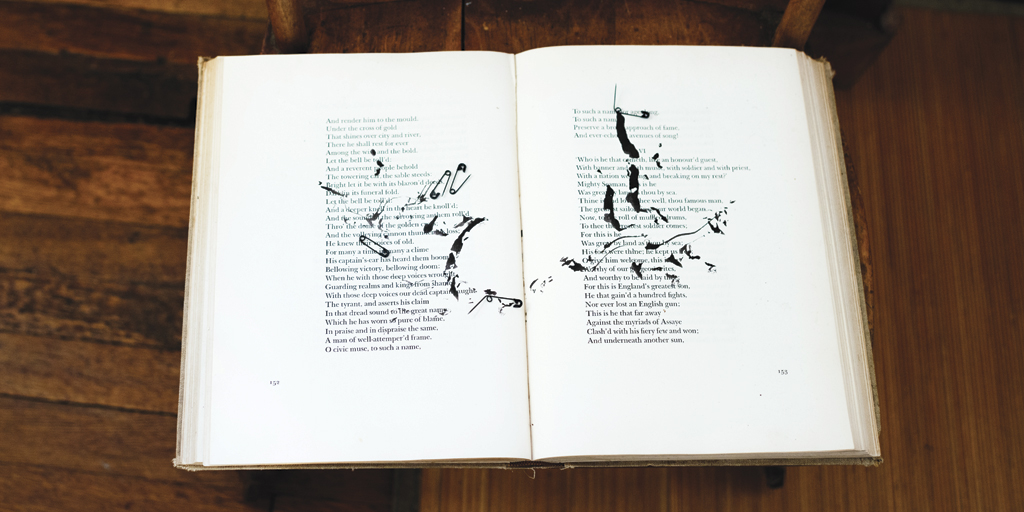

The building also acts as an archive. Its walls are adorned with drawings. Its stair landings are laden with installations. Its apartments are stuffed with canvases. But its most recent acquisition is, for Julie, a personal one.

Inside the building, she showed several hundred paintings in an exhibit titled Womb Room Tomb during last year’s Front Triennial.

Her mother, Virgie Ezelle-Patton, had a local career spanning more than seven decades. But in that time, she received little recognition from Cleveland’s art world. In her life, she had one major solo show. After Virgie died, Julie assembled hundreds of her canvases, drawings, journal pages and sculptures into an apartment-wide art installation as a living legacy to the mother she loved deeply.

After breakfast, Julie and Arcey take me on a tour of the back bedrooms, which they keep available for artists, such as LA-based poet Will Alexander. In one room, someone has penciled a freehand mural of the Cleveland skyline on the wall. Pennies are glued in a row by the footboard.

But first, we go through a door in the other bedroom and emerge onto an enclosed balcony looking out over the construction site. The cinder blocks have risen almost to our level as we stand on the third floor. A gray tarp flaps in the chilly wind.

Soon the four-story development will climb higher even than us, higher than the cottonwood’s branches ever reached.

As we turn inside from gazing at the construction, Julie stops to deliver a foreboding prophecy, a dark echo reflected in Womb Room Tomb.

“This is the death of a project,” she says, warming in the bedroom, “and the artists

associated.”