It took two years to plan.

Two years of penny-pinching, of sharing a meager home and its even smaller bathroom with friends, so that piece by piece — the ivory invitations with burgundy script, the three-tier cake and its teddy bear topper, the shiny, stretch black limo — the wedding was paid for in cash.

The only thing left was for Erin Barr and Jacob Nash to get a marriage license.

Like so many others, the couple submitted an application to their hometown's probate court 30 days before their Aug. 31, 2002, wedding. Yet they were swiftly, uncompromisingly, even rudely, denied. When a Trumbull County magistrate searched county records for Nash's name, he found the then-37-year-old man was once a woman named Pamela.

Hearings before Judge Thomas A. Swift were unsuccessful. He accused Nash of attempting to mislead the court, and letters sent on the couple's behalf only made matters worse. Swift turned to local TV, outing Nash as a transgender man.

"We had a choice to make," Nash says. "Do we withdraw the petition to get married, which is what the judge would have loved for us to do, or do we continue on with this fight because we know there will be people coming behind us?

"So we decided to stand up for what we believe in."

Without their marriage license and half their 225 planned guests — including the groom's father, who refused to attend a wedding unrecognized by the government — Jacob and Erin celebrated their union.

They also became accidental advocates for the more than 19,000 Ohio lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender couples forced to fight for civil rights as large as marriage equality and small as speedy service in a fast-food restaurant.

Since then, there have been victories in all LGBT circles. The federal Defense of Marriage Act was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court last year. Nineteen states now embrace same-sex marriage, with Oregon's and Pennsylvania's bans falling in May. In June, Illinois offered marriage equality and President Barack Obama announced his intention to sign an order forbidding federal contractors from discriminating against employees on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. This spring, the NFL welcomed its first openly gay player when Michael Sam was drafted by the St. Louis Rams — but Sam's televised draft day kiss with his boyfriend sent shockwaves through the media about its appropriateness.

"Sometimes it's frustrating when you hear people say, 'This change is coming so quickly,' " says Alana Jochum, an ally and the Northeast Ohio coordinator for Equality Ohio, which works to advance the rights and protections of the LGBT community throughout the state. "No, we stand on the shoulders of giants who have been advocating quietly — and sometimes very vocally — to mandate that there be more attention paid to these issues.

"It's just now," she continues, "we have the attention of the general populace."

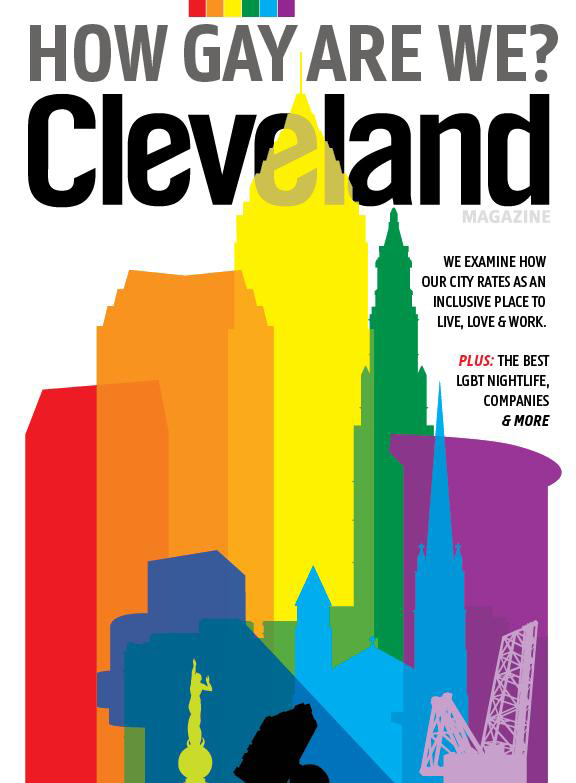

That's never been more true in Northeast Ohio than right now. This month's Gay Games 9 — the weeklong Olympic-like sporting event in which both LGBT and heterosexual athletes compete — gives Cleveland the opportunity to take pride in its progress as an inclusive place to live, play and work, while using the attention to push for even more advances. Talk with members of the LGBT community and their allies, as we've done by the dozens for this story, and you'll discover a generation whose decades-old perspective allows them to appreciate the city's strides and more accepting vibe — and an emerging group who view Ohio's restrictive policies as an ongoing campaign of oppression.

"Cleveland has risen to try to overcome those [challenges]," says Jochum.

Our city scored an 83 out of 100 in the Human Rights Campaign's Municipal Equality Index, which gauges how LGBT-friendly cities are based on criteria that include the benefits it offers same-sex couples to its policies on nondiscriminatory public housing. Akron scored a 48. By comparison, Columbus scored a perfect 100.

While the state still bans same-sex marriage and does not protect individuals from discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, Cleveland created a domestic partner registry in 2008 and extends benefits to the partners and children of LGBT city employees. MetroHealth System boasts one of only a handful of hospital-backed clinics in the nation that caters to LGBT people. Our LGBT center is among the oldest in the country. And our city is home to Case Western Reserve University, one of only a few colleges to offer transgender benefits in its faculty and student health care package.

Yet, the picture is not all rainbow colored. Three local transgender women were killed in 2013, more than 4,700 people are living with HIV in Cuyahoga County, and discrimination and misunderstanding remain as ugly bedfellows. In fact, two of the three taxi companies operating at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport faced objections from dozens of drivers, who refuse to tote LGBT fliers to and from the airport during the games. At the third company, at least two drivers will also take the time off.

The games have put Cleveland smack in the center of the LGBT community's nationwide fight for equality. "It's just an amazing experience to see the spotlight shine on what we have done," says Jochum. "And where we have yet to go."

* * * *

A spiky-haired, fuchsia lipstick-wearing woman, a 76-year-old balding jokester and 10 of their senior-age comrades drag black folding and padded conference chairs to the outskirts of the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Community Center of Greater Cleveland's recreation room, which is packed with secondhand sofas and colorful canvases.

Two days each week, they plunk down the metal seats in a lopsided circle and stretch for their health. It's just one of the offerings at the LGBT Center, where this band of seniors and others gather for discussion groups, health programs and more in its basement location on Detroit Avenue. Just a few weeks earlier, the center hosted a prom for its older members, where men pinned boutonnieres on their beaus and women held hands with their girlfriends as they swayed to music, real music, they say, across a dance floor.

Today, though, Richard Snarsky, trained through the Arthritis Association to teach exercise, creaks his neck from side to side as he instructs the group, "Close your eyes —"

"— But we're missing our queen!" Harry Simmons, the jokester, interrupts, noticing the absence of the woman who'd been crowned queen of the prom.

"I thought we were all queens!" replies Snarsky, and the room buzzes with gentle laughter and a humming air conditioner.

It may be easy to laugh now, but this is the same generation of men and women who, for many years, denied who they were in fear — or even, as spiky-haired Joanna Coleman attests, were unaware loving someone of the same sex was an option.

Coleman, 60, married her high school sweetheart in 1972 and divorced four years later. She was a naive 27-year-old wandering New Orleans' French Quarter when a woman caught her eye, held her gaze.

"I was raised in Chagrin Falls," Coleman says. "I didn't even know anyone who was gay. But I looked at this woman and she looked at me, and in my heart, I started to understand who I was."

Far from her conservative upbringing, in a city known for its laissez-faire attitude about sex, Coleman fell for the woman. They were a couple for months, with Coleman even following her to Florida, until the woman broke her heart.

When she returned to Chagrin Falls in 1981, she rented a room rather than live with her parents. "It wasn't until I moved back home," Coleman says, "that I had trouble."

The '80s were a difficult time for the LGBT community. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officially documented the first cases of AIDS the same year Coleman moved back to town. Many watched friends and partners fall ill and die from the disease during the decade.

"In 1981, I started reading about an illness striking gay guys, and I was thinking, This is not good," Simmons says. "Then people in the community were starting to get sick." By 1984, Simmons had lost a partner. "It was AIDS. I don't remember what it was called then, but it was unambiguously AIDS."

By 1988, hearings by Ohio's State Advisory Committee on Gay and Lesbian Issues concluded that LGBT people "live in a climate of fear and rejection." It also determined that discrimination was "widespread and destructive," spanning employment, housing, health care, domestic relations and public accommodation and services.

LGBT people, their families and property were frequent targets of violence amid a justice system either unable or unwilling to protect and defend them. With shelter and safety in secrecy, they kept to themselves.

From that darkness came bits of light. What eventually became the AIDS Taskforce of Greater Cleveland and the Gay People's Chronicle were both founded in 1984. And near the end of the '80s, Stonewall Cleveland formed to protect and support the LGBT community, and the city's first Gay Pride Festival drew nearly 1,000 people.

Still, when LGBT people went out, they gathered at gay bars off the beaten path: Traxx, 620 Frankfurt Avenue, Dimensions, U4IA, Chapter Two and Keys were all favorites that have since shuttered.

"The bars were set up so that on Friday night there was a certain bar that you went to, and on Saturday night there was a certain bar you went to," explains Ted Wammes, co-organizer of Cleveland's G2H2, a networking social event to bring gay men together.

Established in 2000, the function helps LGBT community members move beyond the few gay bars that remain — Bounce in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood and Twist in Lakewood are two popular spots — to venues throughout the city, many without an LGBT affiliation.

To Wammes and others, it's a sign of progress. "We want equal rights, we want love and to be protected against discrimination," Wammes says. "But beyond that, there is a desire to become a part of the regular community and to feel safe going anywhere."

For the members of the LGBT senior group who lived through those fearful, closeted times and pushed for greater equality, the advances are impactful.

"Ohio is not Massachusetts or New York," says Simmons, who has lived in both, and has attended the center since 2006. "It's also not Mississippi or Alabama or Texas either. Northeast Ohio is a more accepting environment for LGBT people. I mean, even the mayor is friendly to us."

* * * *

Sometime between the moments the plumber stooped beneath her radiator and before he scribbled out her bill, Liz Roccoforte asked him to lift its cover. Though her stomach hadn't yet swelled, she said, she was pregnant and shouldn't lift heavy things.

"He turns to me and asks, 'Is your husband handy?' " recalls Roccoforte, who is the director of Case Western Reserve University's LGBT Center. " 'Could he do this?' "

Roccoforte shook her head in agitated astonishment. She and her partner, Judy, were in photos together throughout the house, in wedding pictures, on the fridge that he was looking at. "I'm just thinking, You're in my house, I don't know you at all, no one else is here," she recalls. "Do I say 'Oh, no, I'm a lesbian?' Because, how awkward — and are you even cool?"

Roccoforte and Judy wed in 2011 in Massachusetts, where same-sex marriage had been legal since May 2004. Just three months earlier, Ohio had passed its Defense of Marriage Act, prohibiting same-sex marriage and failing to recognize same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions.

"The biggest problem I have with living in Ohio and Cleveland are the laws," Roccoforte says. "Our marriage is not recognized here, even though it's recognized by the federal government. We are legal strangers, basically, and we're about to have a baby."

Cleveland is among only nine Ohio cities to offer domestic partnership registries, official, public lists that allow couples to declare their commitment to one another. However, these offer absolutely no legal protection to either person: no tax benefits, no hospital rights, no pensions bequeathed to surviving spouses.

Research for Equality Ohio's current "Why Marriage Matters" campaign shows registered Ohio voters are equally split on same-sex marriage.

"Cleveland was a leader on this," Jochum says. "Because you can't wait for [the state] to establish equality. Sometimes you can make faster inroads and change at a local level."

Cleveland Ward 3 councilman Joe Cimperman introduced the domestic registry legislation in 2008 with 17 of council's 21 members as co-sponsors of the bill. But as they debated its merits, pastors and their congregations began to fill the back of the committee room. They stood, silently, for hours.

"One by one, council members would come up to me and say, 'Not only am I not sponsoring this anymore, but I'm not going to vote for it either,' " Cimperman recalls.

With the help of a few steadfast fellow council members, the legislation was pushed through within three weeks.

"When you think about it in terms of what marriage gives you, a domestic partnership registry doesn't give you anything near that," admits Cimperman. "But what it did was at least certified and honored the relationship that people had."

Since its debut in May 2009, 483 people had joined the registry as of late June 2014.

Rep. Nickie Antonio, the first openly gay person to serve in the Ohio General Assembly, and her partner, Jean, have been engaged for 20 years.

"Our hope is that we will be able to have a legally recognized marriage just like every other couple who decides to do that in the state of Ohio," Antonio says. "If we could get married here, we would have been married a long time ago."

They discussed going to a state where it is legal but believe marriage should be available for everyone. "There are people who can't afford to leave the state," she continues, "so it's really important that we work on getting Ohio to a place where all of the people who would desire to make that public and legal binding agreement with another person will be able to do so without barriers."

As a legislator, she has worked for LGBT rights on other fronts, twice introducing the Equal Housing and Employment Act, which would protect LGBT people from discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodations. Yet the bill has never made it out of committee.

And while there is no explicit regulation or legislation that prohibits same-sex couples from adopting a child together, none have ever successfully done so in the state. Second-parent adoptions, where a spouse adopts his or her significant other's child, are only available to heterosexual couples because the state must recognize the second parent as a spouse of the first.

So although Roccoforte is carrying their child, Judy can't yet become his or her legally recognized parent. "We live in a state," Roccoforte sums up, "in which my partner is not allowed to adopt her child."

The best the couple can hope for is legal custodianship, so that Judy can do things like sign off on the child's permission slips and take him or her to the doctor. They've hired an attorney and are weighing their options.

"We toy with the idea of leaving," she says. "It's not a foregone conclusion that we will stay here forever, especially if we will have to raise a family here and things haven't changed."

* * * *

Wandering through Case Western Reserve University's crowded career fair, 21-year-old Mike Siberski — a double major in aerospace and mechanical engineering — shuffles between two resumes.

Amid lines that boast his academic scholarship and regular slot on the dean's list, a subtle difference stretches across a single sentence on each thick sheet: On one resume, Siberski serves as the program assistant for the university's LGBT Center. On the other, he merely works inside the campus' student center.

As he moves from stand to stand, the senior double-checks his notes. How did this company rate on the Human Right Campaign's Corporate Equality Index? he asks himself again before he selects a resume to hand across the table.

The national organization, which works to advance the civil rights of LGBT people, rates companies on a scale of zero to 100 based on criteria that considers the business's equal opportunity policies, its employment benefits, LGBT competency, public engagement and responsible citizenship.

"We still have a lot of work to do to gain equal protection," says Michelle Tomallo, the board president of Plexus, Cleveland's LGBT chamber of commerce, which works to help LGBT-owned businesses and LGBT allies build their networks.

In 2009, Cimperman introduced legislation to amend Chapter 663 of Cleveland's municipal ordinance and ban discriminatory hiring practices for all municipal employees based on gender identity. Previously, it was legal — as it is in the rest of Ohio and 28 other states — for the city's police, fire or other departments to refuse to hire or fire LGBT employees or people even suspected of being members of that community.

Since its inception in 2006, Plexus has worked to certify companies that are majority LGBT-owned through a national registry. But this April, spurred by the Gay Games, the organization partnered with the city to launch Cleveland's LGBT-Owned Business Registry. The directory is a tool to connect people with LGBT-owned businesses.

"Many municipalities seek opportunities to do business with diverse suppliers," says Tomallo. "But Cleveland took that a step further and said, 'How can we reach out to LGBT-owned businesses to help bring economic equality to more Clevelanders?' "

More than 100 businesses are members of the chamber, which offers networking events, summits, seminars and more.

"It's not like people are putting out their rainbow flag, and it's not like all LGBT businesses are typically florists and hairstylists," Tomallo says. "Part of the work we do is helping people identify these businesses so that they're not hidden."

In fall 2012, when Siberski applied for an internship, he handed over his student center resume. "That's a struggle that [people who] aren't part of our community may not realize that we have," Siberski says. He was later offered the opportunity.

"I kept discussions about my personal life to a minimum," he says. "I had no idea what would happen if I didn't. To my knowledge, there was no corporate policy protecting me."

While at CWRU, named one of the top 25 LGBT-friendly colleges in the country last year by The Huffington Post, Siberski was wrapped in a network of support. Through its Safe Zone Program, more than 600 students, staff and faculty have trained to be LGBT allies, displaying their Safe Zone magnets and stickers in dorms, offices and classrooms as a visible sign of their commitment to helping the LGBT community. The university also helps LGBT people with a preferred name list, LGBT-geared health insurance, bathroom guides and more.

Students whose gender identity doesn't match their given name can register on a preferred name list, which is distributed to staff and faculty, preventing an unknowing instructor from outing a student in public.

"It's extremely rare at universities and colleges, but we have trans-inclusive health care for our students," Roccoforte says of the program, which launched last year. The insurance covers up to $50,000 per year including hormone therapy and several surgical options for transitioning students, faculty and staff who subscribe to the plan.

The university, through its LGBT Center, also distributes maps highlighting single-stall bathrooms throughout campus.

"Bathrooms are a big deal for gender non-conforming people," Roccoforte says. "They are a site of emotional, physical and psychological violence for them. People will yell at them, push them out of the bathroom — it's very uncomfortable."

Beyond campus walls and outside of area LGBT programs, it's rare to find such services.

When Siberski graduates in 2016, he expects to find a job with a company that protects his right to work — even if that takes him out of Ohio.

"Businesses know that if they want to attract the best and brightest talent — who are out and have been out since they were teenagers in a way the generation before us couldn't be out until their 50s or 60s — that generation is not going to work for someone who won't accept who they are," Jochum says. "That's some of the evolution we've seen in the past few decades."

* * * *

Jacob Nash barely left the bathroom for weeks.

"I would come home from work, and he would be doubled over on the bathroom floor, sobbing," Erin recalls. "The only time he would move would be to get up and vomit from the pain."

In 2000, with regular testosterone injections, Nash no longer suffered through menstrual bleeding, but he endured all the other symptoms of endometriosis — a painful disorder in which the tissue that normally lines the uterine wall grows outside instead — including abdominal pain, nausea and fatigue. He sought a gynecologist's diagnosis in Warren.

Though legally still named Pamela, Nash had taken the appearance of a man. Whiskers grew across his face. His breasts were bound. A receptionist, focused on his face, informed Nash that he'd reached the wrong office.

"Going into a gynecologist's office looking like this, most people would think so," Nash admits.

The doctor refused to examine him, he says. "There is nothing I can do for you," Nash recalls the physician saying before scribbling a prescription for OxyContin and leaving the room.

Nash sought a second opinion at another hospital. He says the physician suggested he was seeking a hysterectomy, a surgery in which the uterus is removed, simply because he was a transgender man, not because it was a necessity.

After a year of Medicaid-required hurdles including medications, an ultrasound, CT scan and more, Nash was approved for a hysterectomy.

At 7 a.m., Erin kissed Jacob, as he was now legally known, as medical staff wheeled him away for the two-hour procedure. Six hours passed before Erin saw him again, she says.

Post-surgery, nurses administered morphine to quell his pain — and his audible cries — as Nash lay in a recovery room he shared with women. "More morphine and more morphine and more morphine," he says as his voice lowers, deadpans, "to the point where they shut down my breathing, because they were afraid the other patients would know I was there."

Finally, Erin says, she caught sight of staff wheeling him toward what looked like a regular room. "But it wasn't a room," Erin says. "There was no call light. No phone. No bed. No chair. They started pulling things like extra nightstands and walkers and benches out of the room. It was a storage closet."

Weeks after Nash left the hospital, he says he received a $2,800 bill for a private room.

A recent study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force found that an average of 19 percent of transgender people have been refused care. Nearly 30 percent reported experiencing harassment inside medical settings. And if a medical provider was aware of a patient's transgender status, the likelihood of that person experiencing harassment or discrimination only increased.

Henry Ng, clinical director and co-founder of MetroHealth's Pride Clinic — one of only 12 health centers in the U.S. when it launched in 2007 and the only center in Northeast Ohio that caters to LGBT patients — says it's not only common, but normal, for LGBT people to defer health care treatment because of past experiences or fear.

"I think people can be once bitten, twice shy," Ng says.

Most physicians lack training about LGBT health at all levels of their education. And because so few institutions specialize in LGBT care, there's not enough data to support specialized instruction. Few primary care practices, regardless of their convictions, create an environment that displays awareness and competence regarding LGBT patients.

To cope, according to the task force's study, more than 25 percent of transgender people misuse drugs. Many attempt suicide.

"These individuals are not empowered enough to do much if they're denied care," Ng says. When you can be denied housing, a job and access to health care, your choices may be limited, he explains.

Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, however, both extend domestic partner benefits such as health care to city and county employees' significant others and children.

LGBT people are also more than four times as likely to be infected with HIV than the general population. In Cuyahoga County, more than 4,700 people reported having the disease in 2012 — 3,238 of them lived within Cleveland's city limits. About 62 percent of those were gay men.

The Pride Clinic creates "a sense of space, a sense of safety, for discussions about health care especially for people who have been either marginalized by society or have actually experienced negative health care experiences simply for being gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender," Ng says.

Typically serving patients in their 40s and 50s — though younger generations have begun to trickle in — the center offers primary care, hormonal therapy, STD and HIV screening and treatment, family planning, and surgical referrals through MetroHealth.

The clinic's initial treatment begins with a simple question to each patient: "What do you prefer to be called?" Gender identity isn't assumed based on physical expression.

"After you meet someone where they are and get them to open up about what their concerns are, you [have to] know their health issues well enough to make specific recommendations in terms of prevention or treatment," Ng says.

He treats dozens of LGBT patients each Wednesday from the clinic's space inside the McCafferty Health Center in Ohio City. Ng, who also serves as the board president of GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBT Equality, has learned how to provide hormone therapy to transgender people — an in-demand skill when the clinic began to see non-gender-conforming kids in 2010.

"Whenever LGBT people come to me and ask for help finding a doctor, there are two primary care facilities I can send people to: the Pride Clinic and our doctor in Warren," Nash says. "I say to Dr. Ng all the time, 'When are you going to expand your hours?' "

* * * *

"I want to start off by saying that confidentiality is a key factor in this meeting. What you hear here, stays here — just like Vegas," says Stacey,* a blonde-haired woman with a deep voice and a T-shirt that fits snuggly over broad breasts, as she commences the TransAlive meeting inside Fairlawn West United Church of Christ. The monthly support group is the sister to Cleveland's TransFamily, where transgender and cross-dressing individuals and their families join to vent, question, cry, celebrate, commune.

Tonight, 18 people sit on forest green chairs positioned in a circle inside a gathering room. One by one, to the right of Stacey, who is seated beside Erin Nash, they introduce themselves.

"I'm Julie," starts a woman whose auburn hair just brushes her wide shoulders, "and I started hormones five weeks ago."

"I'm Betty," says a blonde-bob-wigged man. "I was here last month with my wife, but I was in boy-mode then. This is my second meeting. I am a cross-dresser. The positive in my life is that I am about to retire July 1, so I am looking forward to that — but it's also kind of scary at the same time."

"I'm Brad," says a man wearing a fuchsia floral tank top that complements maroon-hued toenails. "I am going to be participating in the Gay Games. I'll be running the half marathon."

The introductions loop back to the center of the circle, where a couple had taken their seats minutes after the meeting began.

"I'm Gary," says the man, a gray-whiskered goatee growing down his chin. "This is m. first time to this meeting, my second time to any meeting. I am just coming to the realization to what is going on within me, and I am having a hard time accepting it and loving myself for who I am."

"I'm Ann, and I'm Gary's wife," says the petite woman beside him, her hands clasped in her lap. "And I'm less freaked out than I was a couple of weeks ago. But I'm along for the ride, trying to figure out if and how we can do this together..."

Gary's chin drops to his chest, his shoulders rise with a stifled sob, and Ann recovers quickly, stretching her right arm around his back.

"...We're planning to do this together," she finishes.

Stacey seizes the new comers' situation as an opportunity. "Does anyone want to share what it was like coming out to your family? Our friends? How they reacted? " She asks the group.

" I took my older boy into a bar and bought him a beer," says Amy, a woman dressed in red from head-to-toe, a gold ankle bracelet wrapped around her right leg.

"Was he 6 at the time?" Ann asks, laughing.

"No. But it helped him get over it!"

"How did he take it?" Gary asks.

"My older boy took it well. My younger boy — eh," Amy shrugs. "At least the communication lines are still clear."

Amy shares how she would sneak away from home with her feminine attire packed in a bag, changing just before she walked into Cleveland's TransFamily meetings. "I'd go through the meeting, and then we would go to Bounce," Amy says. "And then to go home, I would go into the bathroom and change back."

Amy's wife of 34 years — 24 of which she had revealed herself to be a transgender woman — eventually asked her to move into the basement. They recently divorced.

"At the time, I couldn't figure out what the problem was," Amy says. "Well, the problem was she wanted her husband — not me."

A teenage boy, Adam — his small breasts bound beneath his checkered shirt, his feet shoved out in front of him, spread wide apart as he sinks deep into his seat — fidgets beside his grandmother, attending the meeting to support her grandchild, who was born a girl.

The older woman raises her hand. "You've got like five younger people here who are just getting started on this journey," she says "What about safety out in the community? You hear horror stories about gay-bashing and people being dragged behind cars. How do these young ones stay safe?"

Safety is an issue for everyone," Stacey says.

Last year, for example, Cemia " CeCe" Dove, a 20-year-old transgender woman, was stabbed more than 40 times, tethered to a concrete block and dumped into an Olmsted Township pond. Her body decayed for nearly three months before police pulled her from the water. She would be the first of three transgender women killed in the Cleveland area in 2013.

The Plain Dealer and other Clveland media repeatedly, to the dismay of the LGBT community and Dove's family, referred to her as a "him," often only using Dove's birth name, Carl Acoff.

"I called it the Pronoun Fumble," Cimperman says. "If you work with the transgender community, you abide by the pronoun that the person identifies for themselves.

By the time Parma resident Andrey Bridges was convicted of killing Dove after a romantic encounter, the press had gotten its pronouns straight. "But we could do so much more in terms fo being more compassionate to each other," Cimperman says.

In the first four months of 2014, 102 reported acts of global violence — including an 8-year-old boy beaten to death by his father and three 18-year-olds stabbed to death, dismembered or shot — were logged into the Transgender Violence Act Tracking Portal, an online organization that collects data on anti-transgender crimes.

In addition 41 percent of people who are transgender have attempted suicide at some time in their lives, nearly nine time s the national average, according to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.

"Violence sometimes comes from fear," says Equality Ohio's Jochum. "And that fear can come from a lack of understanding. Gender is something so ingrained in us — babies are associated with blue or pink, after all. So when we present the idea of gender fluidity, or that your gender may not be aligned with what your physical birth features were, it's very hard for people to understand."

It's unlikely most people even know of a transgender person in their community. Transgender people represent less than 1 percent of Ohio's population, compared to 3.6 percent of its residents who identify as gay or lesbian, according to U.S. census data.

"The battles that everyone in this room fights, the ones they communicate with their friends and their families, make an impact, says Erin, back at the TransAlive meeting. "Because then, all of the sudden, they can't say those people. They realize the do know us. And they don't hate us."

* * * *

Erin's sentiment will be tested this month as approximately 30,000 participants, family and supporters come to town for the Gay Games. Who we want to be — who the world will see us as — will be tested.

Do we want to be ap lace where same-sex couples, like Roccoforte and her partner, Judy, can comfortably and legally raise their children beyond their own backyards; where kids like Siberski can find a place to work where they're judged by the their performance and not who they choose to love?

As a leader in medical innovation, should we push for our institutions to produce a generation of doctors better equipped to deal with issue of LGBT health and wellness?

How can we get beyond last year's killings and create a place where transgender people feel safe and welcomed walking on our streets and into our shops, restaurants and bars?

Should we push for legislative change in a staid state, or are we good enough as is?

To answer these questions, Cimperman points to our past a s a community that elected Carl sStokes as the first African-American mayor of a major American city; as the hometown of Jesse Owens, who won an Olympic gold medal in front of Adolf Hitler. "It's not an understatement to say we have a city filled with revolutionary giants," Cimperman says.

And the games could be the spark that lights the next flame for change. "I cannot even imagine the power that will be unleashed in the city of Cleveland once you have that many people allowed to be who they are."

Read More: Click here to explore the entire 2014 issue.