The May 25 death of George Floyd and the unrest that followed triggered feelings Kendall Long had never quite experienced. The 15-year-old Black Gilmour Academy sophomore wondered if her white classmates would treat her the same way after.

“My fear is that peers won’t trust as quickly as they used to,” says Long, president of the school’s Black Student Alliance. “I’m not the only one going through this.”

Although she’s been involved with the Black Student Alliance for the last couple of years, she believes the student-run organization can initiate transparent conversations about race relations now more than ever amid the Black Lives Matter movement and a heated election.

“Our mission is to bring Black people together to have a safe space for us to talk about the issues we experience in and out of school,” Long says.

Indeed, that is a focus at Gilmour, which, like most schools, circulated a letter stating its vision and commitment to diversity and inclusion following Floyd’s death. “Inclusiveness can only exist authentically when there is intentionality,” the letter read.

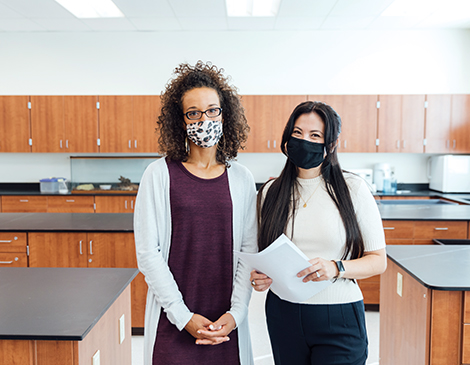

“We are coming off of a pandemic, there is anxiety about going back to the classroom, there is racial unrest in the world and the election is coming up.” says NaNetta Hullum, the school’s director of diversity, equity and inclusion. “These are all pieces that play into student life.”

Meanwhile, institutions such as Laurel School make a concerted effort to create an inviting environment for minority students by hosting open house coffees for prospective Black families.

Laurel also participates in the yearly Breakthrough Schools High School fair by setting up an information table. This has resulted in a few family visits to Laurel.

And to combat the anxiety and bring racial issues front and center instead of pretending like they don’t exist, schools are providing more places to discuss these issues, giving students a voice and focusing on curriculum that can help.

“Students need a place to just unpack it all — unpack the emotion with their peers,” Hullum says. “It’s about having a community that embraces and supports them.”

Spaces To Grow

While the pandemic puts increased importance on school safety, a safe space goes beyond wearing masks and social distancing.

“It also means allowing students to talk about how they feel,” Hullum says.

Creating spaces to discuss race-related issues is a front-burner initiative at schools, some of which have designated diversity and inclusion staff to organize groups, steer discussions and create a community of empathetic stakeholders that includes teachers, staff, parents and students.

“What is really important is that students are aware they can be part of change — they have a voice,” says Lauren Calig, co-director of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging at Laurel. “There has been a lot of movement and calls to action coming from kids, and we can help them become a voice.”

Specifically, following the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Floyd and other people of color, Laurel, which has a student body that’s roughly 30% minority, held a virtual meeting with its Upper School minority students, giving them an opportunity to share their concerns.

“Many of them were outraged — angry. They were sad,” says Candace Maiden, Laurel’s other co-director of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging. “It’s draining when you see repetitive stories and videos of people who look like you being treated a certain way. They needed to be heard.”

By providing a space where they could open up and share their emotions, their white friends, colleagues and teachers were able to understand how taxing it was.

Celebrating differences gives students perspective and builds appreciation for how we all contribute. Long moved from the Shaker Heights City School District, where she felt represented as a young Black woman, to Gilmour, where the student body is 17% minority, in fifth grade. Getting involved with the school’s Black Student Alliance has provided a supportive community for her.

“We need to talk about the issues we have, such as being taught more about Black history than slavery,” she says. “To me, it’s important to have someone in the room who is making sure we are accounted for.”

Hullum acknowledges that civic engagement with each other will help students facilitate open discussions. Conversation spaces, either virtual or in person, will be planned.

“We want students to really listen to one another and share stories, and grow it from there,” she says.

Voices Heard

Laurel’s affinity groups are designed to bring together students, parents and staff in a “huddle,” where they can discuss race-related issues.

“We sit together, and they share their experiences at Laurel, what’s going on in current events and self-identifying — understanding who we are and celebrating that,” Maiden says.

An affinity group for white students focuses on how to be a better ally, and a diversity curriculum is taught to students beginning at 3 years old and continues through high school.

Of course, the conversations are quite different with preschoolers.

“It’s about developmentally meeting kids where they are and using proper terminology, so they will not be worried about talking about race, gender or topics that most adults have never experienced discussing until they are older,” Calig says.

For example, 3-year-olds read a book focused on being a global citizen. A character in the story is treated unfairly, and they discuss why. What does it mean to be a friend — an ally?

“Little kids say it like it is, and they get into personal identifiers, such as saying, ‘I have a friend down the street that celebrates different holidays than I do,’ ” Calig says.

Older students participate in facilitated classroom discussions that introduce topics related to inequality and social justice.

“In the middle school, we focus on equity and how to be anti-racist,” Calig says. “And in the upper school, we have a course called Perspectives, which looks at the culture of the United States and the world now and what the different identifiers are so we can have conversations about that with the girls.”

There are also affinity spaces for parents and teachers. Some affinity spaces are “joint groups,” bringing together students and alumni of diverse racial backgrounds.

“The importance of each group is to create a space where they can process and discuss issues,” Calig says.

Laurel Upper School’s Diversity Fellows allows girls to apply for a role working on concerns about diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging along with school faculty. Last year’s group created an ongoing virtual panel discussion forum for students.

But, Calig says, in order for real change to occur, conversations must happen at home between students and parents. By providing open dialogues and safe spaces, schools can help facilitate that.

“With the issues facing the world now — racial disparities, racism related to COVID-19 and with regard to education during the pandemic, to food access and other resources — these are topics we need to address as adults,” says Calig. “If we don’t start talking about them with students, they won’t feel comfortable discussing it.”