Chico Lewis heaves open the sliding door of the van.

It’s 9 a.m. A middle-aged man waits patiently on the driveway outside West 25th Street’s Hispanic Urban Minority Alcoholism Drug Abuse Outreach Project. It’s next door to South Pointe Commons, an 82-unit public housing facility for the disabled and homeless.

In a black shirt and camouflage shorts, the man clutches a brown paper bag. “How many you have?” Lewis asks, pointing to the bag.

The man leans over a container beside the van’s door. He pours in 20 used syringes. “Twenty-two, please?” the man asks, raising his arms and resting his hands on his shaved head.

Lewis shakes his head. He points to a sign on the van wall: Until further notice ONE 4 ONE.

“We can only give you 20,” says Lewis.

The man shrugs. Lewis grabs two packs of clean 28-gauge syringes, a handful of alcohol wipes and a small tin can for cooking — a toolkit for using heroin.

“Be safe,” Lewis says, handing him the supplies.

“I mean, you know,” says the man.

He tugs his shirt forward so Lewis can read the white letters splashed across his chest: I’m not dead yet!

“That’s what everybody’s wearing now, huh?” Lewis says, laughing half-heartedly. He nudges his partner, Roger Lowe, who sits in the front of the van with his eyes on the street. The pair have been sober for more than 20 years. They understand the struggle.

“It’s sad, but heroin addicts,” Lowe pauses a few seconds, “or people who suffer from my disease, we’re like vampires — constantly focused on our next fix, our next meal.”

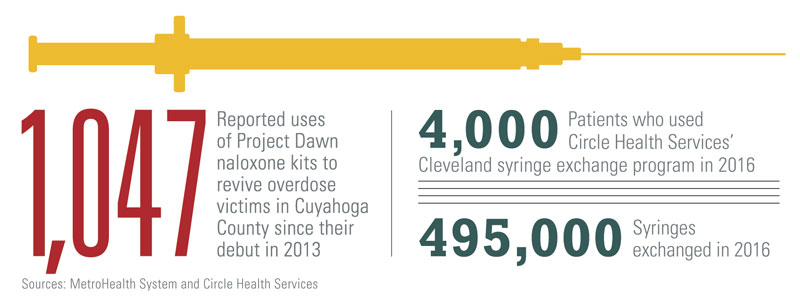

Lewis has operated the Cleveland syringe exchange program through Circle Health Services since 1997, two years after it launched. Last year, the free clinic’s exchange provided 495,000 needles to 4,000 people in an effort to dissuade the sharing of needles, which can spread diseases such as HIV. It’s a stopgap against an epidemic.

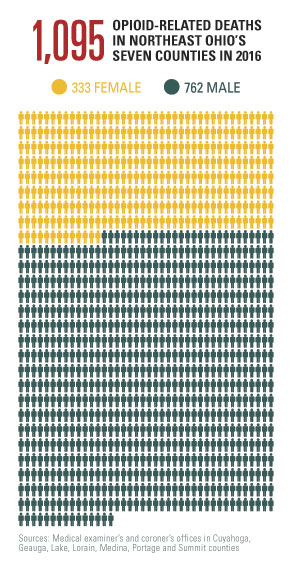

Three years ago, Cleveland Magazine shared the stories of 194 people who overdosed from heroin in Cuyahoga County in 2013. We didn’t know it then, but that was just the first crash in a series of terrible waves. Last year, 1,095 people died in opioid-involved deaths in Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain, Medina, Portage and Summit counties.

It’s made us grim experts in death. In testimony before a senate subcommittee, Cuyahoga County medical examiner Thomas Gilson compared the opioid crisis to a natural disaster and called it a “nationwide public health emergency.”

It’s made us grim experts in death. In testimony before a senate subcommittee, Cuyahoga County medical examiner Thomas Gilson compared the opioid crisis to a natural disaster and called it a “nationwide public health emergency.”

In Cuyahoga County, there are enough people dependent on opioids — including prescription painkillers and heroin — to fill the 67,895-seat FirstEnergy Stadium, Gilson estimated.

The problem is one that’s been made increasingly dangerous by more lethal opioids on the streets — fentanyl, a tranquilizer 80 times more powerful than heroin, and carfentanil, a tranquilizer powerful enough to put down a 12,000-pound elephant and kill a human on contact.

“What else would you call this but a mass fatality event?” asks Gilson.

Throughout Northeast Ohio public agencies are expanding treatment, elected officials are pushing for more funding, police are stepping up enforcement and first responders are increasingly being called to revive overdose victims. But they are barely making a dent.

Like a virus, the epidemic is evolving, staying several steps ahead of its pursuers.

“Any responsible public official that looks at what’s going on would say we have a health crisis here,” says Cuyahoga County executive Armond Budish. “We’ve got people dying every day.”

For Lewis and Lowe, working on the frontlines of the epidemic means they’re confronted with death daily.

“They don’t know what they’re getting into,” says Lewis.

And yet, like farmers market customers browsing for heirloom tomatoes, more than 30 people walk up to the van over the next four hours.

A woman in her 50s arrives with seven needles hidden in a red pack of Maverick 100s. Another woman in her 30s, wearing a pink crop top, carries 200 needles in a Walmart shopping bag.

A young man in a gray T-shirt appears outside the van with an open abscess on his left forearm. The on-staff nurse asks if he wants treatment.

“Naw,” the man says, pointing to the puss-filled wound. “This is a shot about 15 minutes ago.” He walks away with 20 needles.

Behind him, a construction worker in his 20s holds a blue kit from MetroHealth System’s Project Dawn. The program distributed 2,360 free kits of lifesaving naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, in Cuyahoga County last year.

A spray in the nose can bring an overdose victim back from the brink. First responders say it raises the dead — blue from suffocation one moment, alive and talking the next.

He opens the Project Dawn bag. Inside are 30 needles. He leaves with 20 fresh ones, the maximum allotment.

The next customer arrives on a small green bicycle. He’s like most, a regular who comes through at least once a week. He reminisces with Lewis about a mutual acquaintance, an older guy who overdosed in the neighborhood.

“That effed me up,” says the guy. “Ninety percent of the heroin out here has fentanyl in it. You’re not going to find just heroin. You’re not. It’s garbage.”

The nurse cuts in. “So when are you going to get clean?”

He shakes his head and wipes his nose. “One day,” he says.

“Just watch those doses,” says the nurse.

She warns him about the newest rumor: If you cook up the powder and it turns into a clear red liquid, like Jell-O, it’s really strong. He should avoid it, run like hell the other way.

“I haven’t bumped into that yet,” he says, perking up on his bike. “I’ll go ask for that by name.”

“Why?” shouts the nurse. “I just told you that people have almost OD’d on it.”

He laughs.

“You want me to tell you what the addict does?” he asks, leaning forward on the handlebars. “Let me tell you how the addict’s mind works.”

He looks out to the street, holds his breath, looks back.

“I won’t do as much,” he says. “That other guy? The guy who died? That guy was greedy. He did too much. I won’t be a fool like him.”