La Queta Worley-Bell sits on the bench of a bus shelter looking east on Corlett Avenue near Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

Remnants of a late-fall snow coat the ground and the rooftop of John Adams High School across the street. Though the glass of the shelter blocks Worley-Bell from some of the wind, she is still bundled up in a hat, gloves and puffy coat to protect her from the 22-degree chill.

She exudes patience as she sits with her arms crossed on her lap.

“I’m used to the waiting,” says the 47-year-old seasoned bus rider.

Fourteen minutes later, the No. 15 bus pulls up to the stop like a caravan ready to shepherd people through the cold streets.

Worley-Bell, whose mission today is grocery shopping at Dave’s Supermarket in Ohio City, slowly stands to board.

“This is one of the older buses,” she remarks as if she’s a mechanic.

She shows the driver her disability pass — she had screws put into her foot in 2017 — where her picture is completely faded from the well-worn ID card and sits down towards the front on the plastic bus seat with faded blue-and-pink patterned RTA-branded fabric that looks like it was lifted from the 1970s.

The aisles on these older buses are narrower than the newer models, which proves problematic for riders with strollers, wheelchairs or the plethora of shopping carts that crowd the interior at the beginning of the month when paychecks are exchanged for groceries.

Worley-Bell stares out the window and points out every neighborhood through which the bus passes, from the churches to the charter schools, from the beauty shops to Cuyahoga Community College’s new construction on its Metro campus.

Not only does she know these streets, but she knows them from these bus windows.

The lifelong Clevelander has never had a driver’s license, and only briefly had a car 30 years ago.

“My great-aunt gave me her old car for $200 when I was 18,” Worley-Bell remembers. “She was really old, so she couldn’t teach me how to drive. So, I let the car go. It sat, then just rotted.”

She spouts off numbers of bus routes by heart, having memorized which ones go where and on which days. From her home in the Union-Miles Park neighborhood, she spends 6 to 8 hours a day using a combination of the bus and the Rapid to volunteer at a church on West 65th Street, visit her 24-year-old daughter in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, go to church on Sundays (which requires an entirely different route, as some crucial bus routes don’t run on the weekends), and to look for work.

It is this last pursuit that proves difficult.

“It has to be some place I want, but it also has to be some place I can get to,” sighs Worley-Bell, who is currently unemployed. “That’s not always easy.”

Worley-Bell’s experience is not uncommon. Far from it, says Bethia Burke, incoming president for the Fund For Our Economic Future, a philanthropic collaborative devoted to improving the economy in the region.

“Northeast Ohio has been in a pattern of no-growth sprawl for decades,” she explains. “We have the same number of people and the same number of jobs, but they are spread over an ever-increasing footprint.”

The result is that the physical distance between people and jobs continues to expand at a rapid rate. For the average Northeast Ohio resident, the number of jobs close to where they live declined by 22% from 2000 to 2012, while the number of nearby jobs for those living in high-poverty neighborhoods in Northeast Ohio declined by 31%.

With farther to go to get to a job, people need to have a reliable, flexible means of transportation such as a car, but that’s something not available to the entire workforce.

Thus, individuals must turn to expensive ride-sharing services, depend on others for a lift or hop on public transportation, a method that may be dependable most times, but often isn’t direct, especially as available routes diminish the further you travel from the city’s core.

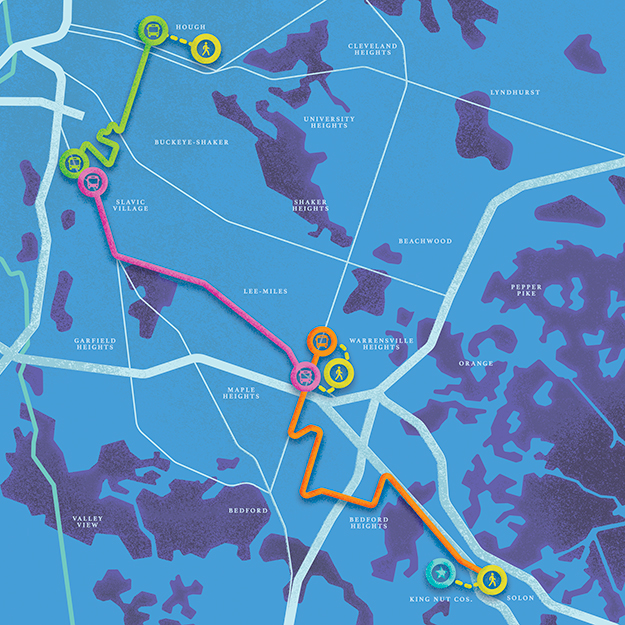

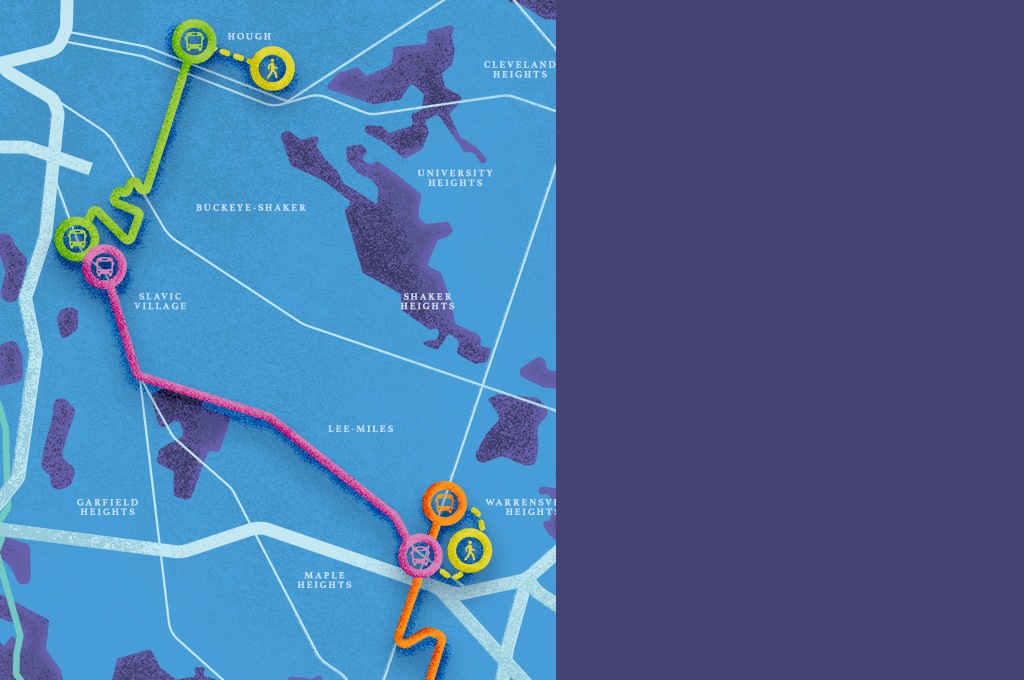

Solon is one of the fastest growing job hubs, says Burke. With four different bus routes from Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood, the shortest being an hour and 55 minutes with two transfers, commuting to work proves challenging for those who work at companies such as nut manufacturer King Nut Cos.

“In a car, it would be less than 30 minutes,” Burke says.

The results of this transportation morass are wide and varied. Employers in far-flung exurbs such as Mentor have a difficult time filling open positions in manufacturing. Potential employees don’t apply for certain jobs due to a lack of transportation. Current workers fall into absenteeism due to a sudden change in a bus route or a car pool that doesn’t show up.

Without a car, employees (potential or current) can’t get to their job. But without the job, they can’t afford a car.

That central quandary inspired the rollout of the Paradox Prize in 2019, a series of grants awarded by the Fund For Our Economic Future, the National Fund for Workforce Solutions, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cuyahoga County, Cleveland Foundation, the Lozick Family Foundation and DriveOhio.

Designed to support early-stage concepts that address the transportation challenge, it’s named after the no car, no job/no job, no car transportation paradox. The creators hope it will inspire a wide range of possible solutions and motivate companies to change the logjam that prevents so many Ohioans from getting to work.

“We can’t think about business retention or economic expansion or even environmental sustainability without thinking critically and introducing new ideas about how the workforce actually gets to their jobs,” says Burke.

Since rolling out in June 2019, round one of the call for proposals netted more than 50 ideas for improving the mobility of Northeast Ohio’s workforce. The first batch of entries represented nonprofits, corporate entities, individuals and shared collective proposals.

Over the next three years, up to $1 million will be awarded to support up to 15 pilot programs. This includes winners from rounds one and two, such as Akron Metro which will test a door-to-door, on-demand car service connecting workers to jobs in Northern Summit County, and Manufacturing Works which will use church vans to transport employees in Glenville and Lee-Harvard to jobs in Solon and Strongsville.

The third round closes Jan. 15. As the ideas begin to launch, the very idea of transportation is being challenged.

“People need work and companies need people,” says Burke. “To bridge that gap, we have to fundamentally rethink how we look at transportation.”