We have been here before.

So much talk of the Cleveland comeback with our downtown building boom and Republican National Convention-fueled makeover makes it difficult not to think about our mid-1990s civic renaissance. In 1995, The New York Times headline proclaimed " 'Mistake by the Lake' Wakes Up, Roaring" as downtown's stadiums and lakefront development created a "new face and new style of a city that for a long time had little panache."

But it wasn't just the media who became enchanted with our freshly minted charms — even the scholars were feeling it. The academics, however, had a Lake Erie-sized caveat. There was a divide in the region's comeback, noted the authors of the 1997 study "The Rise and Fall and Rise of Cleveland," with areas separated by characteristics of "capital investment and disinvestment, industrialization and deindustrialization, suburbanization and ghettoization, white flight and a black underclass, the growth of services, and a [high-skill and low-skill] dual economy."

Prophetic then, those words serve as a warning now. The paradox of Cleveland's comeback, if not an urban American comeback, is that the more a city returns, the greater the number who get left behind.

Rob English splits his time between Baltimore and Cleveland. He has been doing so for nearly three years.

A former Army infantryman, he serves as supervising organizer for the Greater Cleveland Congregations, a network of local faith and community-based organizations working for social justice. His experience in Baltimore since 1997 gives him a different perspective on his work in Cleveland today. "You have to meet people where they're at, listen to them, and find ways to act in their mutual interest," he says.

English marched with the Cleveland group in late May after the Michael Brelo trial verdict to demand comprehensive criminal justice reform. As the demonstrators from about 40 religious congregations walked arm-in-arm along downtown streets to City Hall and the Justice Center, it was peaceful — unlike what happened in Baltimore a month earlier. There, the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray in police custody prompted violent social unrest.

"Baltimore is about seven to 10 years ahead of Cleveland," says English.

Odd as it sounds, what English means is that Baltimore's economic resurgence has been longer in the making — and that may be a good thing for Cleveland.

Baltimore's signature project, the cleanup and rehabilitation of Baltimore's Inner Harbor with its world-class aquarium and science center, began in the 1980s. Oriole Park at Camden Yards, an architectural model for Progressive Field, opened in 1992.

With the beautification came a change in the city's demographics. Today, nearly 27 percent of Baltimore residents have college degrees, compared to 16 percent in Cleveland. Baltimore's median income ($41,385) is $15,000 higher than here. Cleveland's poverty rate sits at 35 percent, 12 percentage points more than Baltimore.

But the benefits in Charm City are not evenly distributed. White city residents earn nearly double that of black city residents. Baltimore also had the ninth worst wage disparity between high- and low-income workers in the nation, according to the Martin Prosperity Institute. So, while the physical redevelopment is apparent in the eyes of all Baltimoreans, the effect is uneven in their temperaments.

English, 46, recalls a talk he had with an African-American woman from East Baltimore several years back. She could see the Inner Harbor off in the distance from her neighborhood.

"Let me tell you about my anger," she told him. "Every morning when I wake up and take the kids to the bus stop, every morning I look down and see the harbor, and every morning I get angrier."

Her experience is more than an isolated one, says English. In Baltimore, people saw aspects of the city improve year after year. Yet so many weren't a part of it. Eventually tensions built, and the Freddie Gray incident ignited it.

"Now, Cleveland is beginning a renaissance," English says. "But there is room to come together so you're not two cities."

Thomas P.M. Barnett's book The Pentagon's New Map is more than a decade old. But its message is no less relevant.

"Disconnectedness defines danger," he argues.

For the expert geostrategist, the world is split between two types of geographies: the Core, where "globalization is thick with network connectivity, financial transactions, liberal media flows, and collective security," and the Gap, or areas disconnected from globalization and defined by poverty, low education rates and "the chronic conflicts that incubate the next generation" of instability.

"We ignore the Gap's existence at our own peril," concludes Barnett.

It is a useful model in understanding what's occurring in Northeast Ohio.

Consider that, according to a Brookings Institution study, Cleveland and Seattle led the nation with the biggest percentage increases in high-income households from 2012 to 2013. Yet, research from Rutgers University revealed Cleveland also has one of the largest increases in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty since 2000.

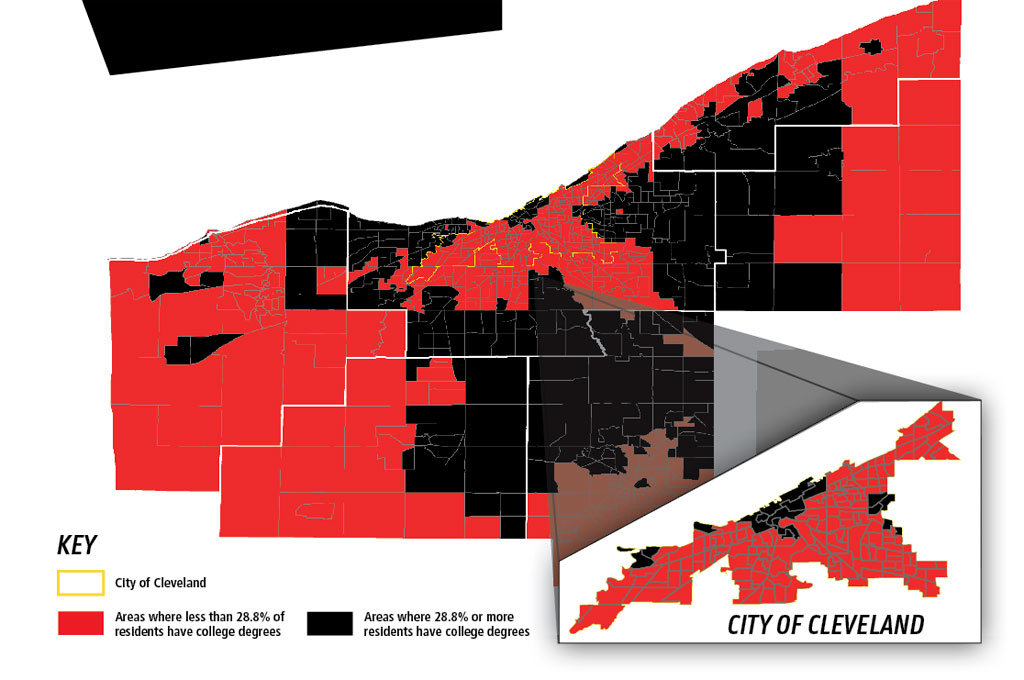

This division is further evident when mapping the concentration of Northeast Ohio residents with college degrees. Higher educated areas are centered in downtown, Ohio City, Tremont, Detroit Shoreway and AsiaTown, which have each seen double-digit percentage increases in residents with college degrees since 2000, as well as along the lakeshore, near University Circle and in various suburban and exurban clusters. Meanwhile less educated areas are grouped in the city of Cleveland outside the urban core and in the rural exurbs.

Simply, areas of Cleveland that are revitalizing are part of the globalizing Core. The isolate neighborhoods, or those experiencing higher levels of violence and poverty, comprise the Gap.

In fact, for a number of quality of life indicators, outcomes in various East Side neighborhoods are below that of developing nations. A recent PolitiFact article showed that infant mortality rates were worse in select East Cleveland neighborhoods than in North Korea, Uzbekistan, Zimbabwe and the Gaza Strip.

According to data by Case Western Reserve University, homicide rates for sections of the city are similarly comparable. In 2010, homicide rates in Ward 1, comprising parts of the southeast side, and Ward 9, which entails Glenville, are similar to Guatemala and El Salvador.

What's happening here is not unlike cities such as Chicago, Baltimore, Miami and Brooklyn, New York, where the spatial patterns of having and not having mean poverty gets pushed together, not alleviated. When cities evolve as separate and unequal, they create a deepening sense of alienation and marginalization.

"The economic and social frustration could be expressed in more recourse to violence," says Mark Joseph, director of the National Initiative on Mixed-Income Communities at Case Western Reserve University.

Revitalizing neighborhoods have more "eyes on the street," says Joseph, who examined the effect in the Second City while at the University of Chicago. And more vigilant policing can "push gangs into more constrained areas of the city and into more conflict with each other."

In the first nine months of 2015, for example, there was a 40 percent increase in gun homicides compared to 2014.

"As we are seeing in our city, innocent bystanders suffer the consequences as well as those directly targeted," Joseph says.

In a span of a month, a 5-year-old, a 3-year-old and a 5-month-old were all victims of drive by shootings from gang violence that has boiled over in various East Side neighborhoods.

After the youngest, Aavielle Wakefield, was killed, Cleveland police chief Calvin Williams stood at the crime scene on East 143rd Street in Cleveland's Mount Pleasant neighborhood. It was night. The street was lit by the television crews. With Mayor Frank Jackson by his side, the chief demurred about the senseless tit for tat, the need to catch the perpetrators.

Suddenly, his face went from firm to fragile. "To the family ... it's tough ... it's tough," he said in tears. "This should not be happening to our city. And we got to do something about it."