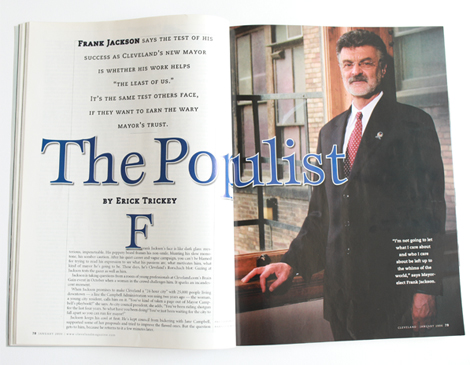

Frank Jackson's face is like dark glass: mysterious, impenetrable. His peppery beard frames his non-smile, blunting his slow monotone, his somber caution. After his quiet career and vague campaign, you can't be blamed for trying to read his expression to see what his passions are, what motivates him, what kind of mayor he's going to be. These days, he's Cleveland's Rorschach blot: Gazing at Jackson tests the gazer as well as him.

Jackson is taking questions from a room of young professionals at Cleveland.com's Brain Gain event in October when a woman in the crowd challenges him. It sparks an incandescent moment.

When Jackson promises to make Cleveland a "24-hour city" with 25,000 people living downtown — a line the Campbell Administration was using two years ago — the woman, a young city resident, calls him on it. "You've kind of taken a page out of Mayor Campbell's playbook!" she says. As city council president, she adds, "You've been riding shotgun for the last four years. So what have you been doing? You've just been waiting for the city to fall apart so you can run for mayor?"

Jackson keeps his cool at first: He's kept council from bickering with Jane Campbell, supported some of her proposals and tried to improve the flawed ones. But the question gets to him, because he returns to it a few minutes later.

"I'm not doing this for me, whether or not the young lady had her point," he says. "If this were about me, I'd stay as council president and be safe and secure." Or, adds Jackson, 59, he could retire and get 75 percent of his pay.

Suddenly, he lights up with anger. "I think me and Mayor Campbell are irrelevant in this, if you want to know the truth! What's it got to do with me? It's got to do with you. It's got to do with you young people and the future of this city."

He starts thumping the podium with each key word. His goal, he says, is "making sure that we as a city prosper and our people prosper! We live in a country that's professed that capitalism is for the purpose of improving the quality of life and the standard of living for everyone, even the least of us! We live in a country with a representative democracy and a constitution that guarantee the lack of oppression on people!

"We have a right to these things! And I'm not going to sit by and, just for the sake of being safe [and] avoiding adversity, let what I care about and who I care about be left up to the whims of the world!"

There it is. For a brief moment, clarity, vulnerability: Frank Jackson, Cleveland's first populist mayor in 25 years.

He's the first mayor in a long time to come from the ranks of the poor, to say they're his first priority and lead from the bottom up, not the top down. He not only grew up in Cleveland's poorest neighborhood, he still lives there. His career has been dedicated to making sure the poor aren't "left to the whims of the world."

The test of his success as mayor, he told campaign audiences, should be "whether the least of us are better off because of what I do."

That not only makes him different from Jane Campbell, the suburban-raised, middle-class to the bone, social-worker mayor he unseated. He's also different from his '90s-era ally, Mike White, the bully-pulpit-pounding, ego-driven, big-project strongman mayor. And George Voinovich, the peacemaking, arm-in-arm-with-business mayor. But also Jackson has little in common with Cleveland's last populist mayor: the young, pre-New Age Dennis Kucinich, arrogant bully for the "little people."

Populist often means fiery speech-maker, rabble-rouser, demagogue. Yet Jackson's speeches douse fires, not start them. He's quiet. He'd rather govern than campaign.

No mayor of Cleveland in the last 30 years has exuded less charisma before crowds. And, judging by voter turnout — mediocre in November, abysmal in the primary — no mayor of Cleveland in 30 years has taken office with less excitement or enthusiasm about his or her leadership.

Campbell and her supporters tried to paint Jackson as a stubborn obstructionist during the mayor's race, hoping that ominous Rorschach blot would tap the decades-old fears of conservative, business-friendly Clevelanders: That any leader who cares about the poor will let class-envious councilpeople mau-mau businesses right out of town, or let lazy City Hall bureaucrats lay welcome mats full of molasses, or kill projects by extracting too much tribute from them.

Jackson and his fans turned stubbornness into a compliment: He's principled. Plenty of businesspeople took Jackson's side, insisting he'll help spark prosperity — as long as it truly helps Cleveland's residents.

The new mayor, who takes office Jan. 2, measures the city's progress differently than many people do. A suburbanite might get cheered up about Cleveland's future when she sees a new building open downtown.

Businesspeople are usually encouraged a few months earlier, when they see "cranes in the air" — construction equipment hanging in the sky over a new project. Frank Jackson looks at the same scene and asks: Who's operating the crane? Who's getting the jobs? Are they Clevelanders?

When Jackson's supporters and his critics argue about his stubbornness, they're orbiting, but not landing on, another key to understanding the new mayor: how wary he is.

Jackson's fans testify to his honesty, integrity, unmovable principles. He does not often reciprocate. You'll rarely hear him vouch for other people's good intentions. "I have no hidden agenda," he often promised in the campaign — clearly implying other candidates did.

Sometimes, if you talk to Jackson long enough, he'll reveal a note of suspicion: Does everyone really have poor people's best interests at heart? Does everyone who pays lip service to improving Cleveland really care?

Jackson scrutinizes people's actions, looking for their motives. If he thinks those motives are impure, he goes to war. That's why he fought predatory lenders, those who wanted to tear down housing projects in his ward, even Jane Campbell. You could spin that trait both ways too: shrewdness or paranoia? Mistrust or vigilance?

Army private Frank Jackson returned from Vietnam in 1969. His beloved Central neighborhood, where he'd lived all his life, was dying.

"Everything was destroyed," he recalled in July. Urban renewal had left the poorest of the poor living in public housing, surrounded by dilapidated houses, no development, vacant land where there used to be homes and businesses. "It was like watching your home go to hell. So you just stepped into responsibility."

Jackson helped his friend Lonnie Burten get elected to city council in 1975. Both fought to improve and preserve public housing.

By 1989, when Jackson won his late friend's former council seat, the federal government had declared Central's public housing "nonviable," cutting it off from renovation funds, marking it for demolition. The government tore down public housing throughout the country in the '90s, justifying it as a benevolent attempt to break up a "culture of poverty" and integrate the underclass into middle-class neighborhoods. Jackson didn't buy it.

"Every piece of logic and theory sounds perfect," he says. "I often look at the motive behind it."

The federal government "was a great participator in creating slum landlords," he argues. "They knew for years that Longwood Apartments and public housing were in deplorable condition, but they continued to award [them]

tens of millions of dollars." So when the feds wanted to "give people Section 8 vouchers to get rid of them, under the pretense that they're concerned about their well-being — I wasn't going to allow that!"

Instead, Jackson attracted developers to his ward. He got them to build new private and subsidized housing that included neighborhood residents. He had leverage to make the deals he wanted: federal grant money he controlled, which he used in innovative ways — as supplementary funds that helped developers build the new developments and as $10,000 grants to some longtime neighborhood residents to lower the cost of their mortgages on the new homes.

Today, you can drive down Central or Woodland avenues, from East 30th to East 55th streets, and see Frank Jackson's biggest accomplishment: hundreds of millions of dollars in new investment. Off Central, near Jackson's rambling older home, rise dozens of new houses, decorated in white or blue siding or Tyvek HomeWrap, the universal wrapping paper of brand-new suburban prosperity. One street is named Burten Court in honor of the former councilman, who died in 1984.

Woodland is lined with a vibrant jumble of red and tan brick townhouses with yellow, blue and green siding.

They replaced the scary, decrepit Longwood subsidized housing development, whose conditions Jackson and Burten often fought to improve. Longwood's residents got first dibs on moving into the townhomes. Nearby, a new Dave's Supermarket stands at a corner that used to be an open-air drug market.

Meanwhile, at City Hall, Jackson fought to help the poor. He insisted that regular Clevelanders should benefit when government is involved in development. The three most important laws he's helped pass, he says, are the city's living wage law, predatory lending law and resident employment law, passed in 2001, 2002 and 2003.

The living wage law, whose details Jackson spent 18 painstaking months negotiating with small-business advocates and a workers'-rights group, requires some companies that do business with the city to pay their workers at least $10 per hour.

The lending law, passed soon after Jackson became council president, fought an aggressive wave of predatory loans sweeping the city. "He obviously led the charge," says county treasurer Jim Rokakis. "[Council] realized this cancer was killing neighborhoods in the city of Cleveland. He acted, and he did it over the objections of many of the banks." The law requires counseling before Clevelanders sign a high-interest loan, and it bans high-interest loans that also have another exploitative provision, such as balloon payments or very high fees.

Next, Jackson accomplished something he'd pursued for his whole career as a councilman. For years, he and councilwoman Fannie Lewis had insisted that City Hall should use city-funded construction projects to help more Clevelanders get jobs in the sometimes-clubby construction trades. Now, it's the law: If a construction project gets more than $100,000 in subsidies from the city, 20 percent of its workers must be city residents.

Passing the ordinance, known as the "Fannie Lewis Law," was Jackson's proudest moment at council.

Jackson's falling-out with Campbell began one night in March 2004 at a city council committee meeting. There, Jackson learned that Campbell's administration had left the Fannie Lewis Law out of a contract it submitted to a city board. Angry, he asked why. A week earlier, the federal and state governments had told the administration that the law couldn't apply to their grants because they object to hiring quotas based on geography.

Jackson was furious, thinking Campbell was trying to slip something by him, that she wasn't eager to enforce the law he so valued.

He told reporters he would never trust Campbell again. "There was, in my opinion, some effort to go around the law by the administration," he told Cleveland Magazine this November.

But not everyone saw it that way. "Everywhere I've gone, she's always championed the Fannie Lewis Law," says city councilman Zack Reed. "I've never seen [her administration] waver on that law, never." Campbell negotiated side agreements with contractors to meet the law's hiring goals. She also sued the state and federal government. That wasn't enough for Jackson.

"Once he decided that he was not satisfied with what I was doing, no level of communication or information ever satisfied him," Campbell says.

Jackson threatened to withhold approval of contracts for the $300 million Euclid Corridor project if the law wasn't included — a dare Campbell claimed jeopardized the whole project. Then Jackson brokered an agreement with the Regional Transit Authority to hire Clevelanders for the project. He and Campbell were still sniping over the best way to defend the Fannie Lewis Law at their first debate this October.

Jackson also fell out with Campbell for other reasons. His weekly meetings with her frustrated him; he says he often "had to be more assertive than I thought I should have been to get decisions made," especially during the city's 2003 budget crisis and layoffs. He started to question parts of Campbell's proposed budgets, says the mayor kept him waiting for answers on plans to redeploy police, claims she often told him she'd do one thing, then do another. ("Clearly, with hindsight, it wasn't wise to have private meetings," Campbell responds. "The interpretations are very different.")

Finally, when the school levy failed in November 2004, Jackson says, he started thinking seriously about running to unseat Campbell. He announced his candidacy two months later.

The lesson: Don't cross Frank Jackson.

Ink blots might reveal Jackson has some trust issues. The feud left one Campbell aide complaining bitterly that Jackson is too suspicious of Campbell and others. "It's almost like he lives in a world in which things are never to be taken at face value: people's motives, their intentions," the aide argues.

"I think he's very slow to trust," Campbell says. "He keeps his own counsel."

So I ask two people close to the new mayor, "How long does it take to earn Frank Jackson's trust?" They both laugh.

"A very long time," says Dominic Ozanne, head of Ozanne Construction. "I hope I've earned it! • He's very quiet, very reserved, very cautious." Then Ozanne backtracks a little. "I don't think he's any more cautious than you or I are."

"I guess I've always had a good relationship with him," says Arnold Pinkney, Jackson's campaign manager. But Pinkney agrees, "His is about a question of trust." Where does that come from? "When you come up the hard way economically, there's a tendency to know how to survive. To survive, you have to know who are your friends."

Five days before the election, Jackson appears in Public Square with several West Side politicians who've defected from Campbell to his camp.

"I'm encouraging Frank Jackson to continue to walk softly and carry a big stick," county prosecutor Bill Mason tells the TV cameras. He hands Jackson a long, sawed-off shovel handle. "Frank must endure personal attacks if he's going to get the city out of a death spiral."

Jackson takes the mike, wielding the stick. "I'm going to put this down for a minute. I might have to use it later." His supporters laugh.

He turns to a plaque on the statue of Tom Johnson, mayor of Cleveland 100 years ago, and reads: "He found us groping, leaderless and blind. He left the city with a civic mind."

It's a nicely staged event — which Channel 3 reporter Tom Beres quickly shakes up by asking why Jackson voted against Cleveland Browns Stadium and the sin tax that funded Gateway.

"I'm pro-Cleveland," Jackson says. "I voted against projects that would not hire Clevelanders."

In the '90s, Jackson was one of the many people who asked why Cleveland was spending so much money on sports stadiums and not enough on education and the poor. So in the second debate this fall, Campbell cast Jackson as an obstacle to the building of Jacobs Field, Browns Stadium and Quicken Loans Arena, stoking the fear that Jackson will get in the way of future progress.

"After the fact, you can't look at downtown Cleveland without Gateway," Jackson concedes. "But the point is that it's not my job • to just roll over at the expense of the city of Cleveland or its residents."

Gateway and Browns Stadium didn't guarantee jobs to county or city residents, he argues. And he saw other flaws in the deals: bad lease provisions that saddled Gateway with years of debt and obliged the city to pay the football stadium's property tax and liability insurance. "I will drive a better deal for Cleveland,"

Jackson says. "People need not fret."

Still, when Jackson announced he was running for mayor, a buzz swept through many businesspeople downtown.

"Why are you supporting him? He's anti-business!" That's the typical first reaction that Bob Smith, president of Spero-Smith Investment Advisers, says he got when he pitched Jackson's candidacy to fellow CEOs. Smith, a past chairman of the Greater Cleveland Partnership and the Council of Smaller Enterprises and Jackson's biggest supporter in the business community, blames headlines about the Fannie Lewis Law, the living wage law and Steelyard Commons.

"This guy wants job creation more than anybody," Smith says of Jackson. "He sees when he comes out of his front door in the morning who's working, who's not and the impact on his neighborhoods." Jackson speaks convincingly about wanting to create incentives for business growth and eliminate disincentives, Smith says.

However, he adds, "He's not going to take the initial line of what business wants."

Businesses, too, must work to earn Jackson's trust. Smith says he once asked Jackson why the city seems to put obstacles in the way of growth. Jackson replied that he'd heard too many false promises of new jobs from businesses looking for city subsidies or tax abatements. Too often, "they got their money but we didn't get the jobs," Smith recalls Jackson saying. "That makes you trust but verify."

Smith became a Jackson fan during the living-wage negotiations, when Jackson agreed to remove record-keeping and reporting requirements that Smith thought too burdensome on business.

Likewise, Jackson impressed National City CEO David Daberko when they met to discuss the predatory lending law. Daberko felt the original version of the law discouraged legitimate banks from lending in the city, and he arranged a meeting. "I was very impressed with his willingness to listen to the other side of the story, and to admit that he didn't know everything," Daberko says.

Council amended the law to focus it on the lending companies that were the worst offenders. Daberko still isn't crazy about the law, but he says Jackson swayed him a little. "I didn't actually think there was a need for legislation, and he pretty much convinced me that there was," he says. Daberko supported Jackson in the

election and is helping him with the transition.

It's hard to find anyone willing to question Jackson's past decision-making on the record now, during Jackson's post-election "honeymoon." People either think it'll make them sound like they're not giving him a chance as mayor, or they don't want to cross him because they may have to work with him. But Jackson's supporters know the common criticisms of him by heart.

"Part of the knock on Frank is that he is a populist, that that limits his vision," says Fred Nance, managing partner at the law firm Squire, Sanders and Dempsey. But Jackson is also a "pragmatist," he says. "He will admit he doesn't have the expertise to know all the ins and outs. • There's not a pride or ego factor that limits his ability to cooperate with people."

Take Steelyard Commons. "He's taken a bum rap," Nance says.

When Wal-Mart temporarily backed out of the giant shopping center project, seemingly dooming it, The Plain Dealer and others blamed Jackson for not killing Joe Cimperman's bill that would have barred Wal-Mart from selling groceries.

"What Frank was trying to do," insists Nance, "was reconcile the interest of the developer and the project moving forward on one hand, and the neighborhood and smaller stores," which felt Wal-Mart threatened them, on the other. At one point, Jackson announced a compromise, which later collapsed.

So what will Jackson do as mayor? No one knows exactly.

"We're going to find out, aren't we?" says Campbell, who promises to support Jackson but adds, "There are a great deal of unknowns."

Jackson got elected without making many specific promises. He stuck to a simple message, a few talking points.

His position papers are filled with small, sensible ideas, but only his promise to create a "24-hour city" was visionary enough to make into his stump speech. Jackson's campaign staff guessed correctly that voters had already decided not to re-elect Campbell, and that Jackson just needed to present himself as competent and trustworthy.

Supporters promise that Jackson's a quick study and a good listener. They predict he'll grow into the job and show flexibility. They point to his decision to back off his plan to ask the school board to resign. Skeptics, amid the optimistic spirit of Jackson's honeymoon period, seem eager to be pleasantly surprised. That may be why the mayor-elect's announcement that he'll appoint an aide to work on regional issues made The Plain Dealer's front page: It defied the image of him as a parochial ward councilman at heart.

Jackson's best statement about his plans may have come at that Brain Gain event in October. When someone asked him what he'd do in his first 200 days, he still seemed upset that the young woman had challenged him, and his answer rose to a crescendo. He promised to create "a sense things are going to get better." A transition team of experts will advise him on hiring for key positions. Then he'll hire people who are loyal as well as competent. "I don't cross nobody. I don't want to be crossed." He promised to make City Hall more efficient "at a reduced cost" and to "look at the operation of the school system" and improve it.

"As of 200 days, you should see the city moving [and] progressing," he says. Then, he says, young, mobile professionals will look around the city and say, "You know what? I'm going to lend my expertise. I'm going to help. And maybe I won't move out of town. Maybe I'll just stay here and put my roots down here." Maybe, he added, a CEO he just partnered with will say, " •Look, it might make better sense to go to Chicago. But Frank, I like this city, I love this city like you. Let's see if we can work out something where we can make this city prosper so it makes sense to for me be here.'

"That's what I have to do," Jackson told the crowd. "And if I don't do that in 200 days, then I'm a failure.

Q and A

We sat down with Frank Jackson in November to talk about his plans for how to unite the city, improve the schools, work with the best of Northeast Ohio and handle the possibility of casinos in Cleveland.

Cleveland Magazine: At your victory party, you promised to look at Cleveland as one city, not as East Side and West Side, not as white and black. Many politicians have promised that before. How will you improve race relations and cooperation between the two sides of town?

Frank Jackson: I don't think it's really about improving race relations as much as it is carrying out what you said. If I look at what I do in the city of Cleveland not as black, white or Hispanic, or East Side or West Side, but look at it as doing it for Cleveland, that's a message from me.

If you do not play up the issue of differences or what divides us, then it will tend not to be as prominent. Part of my campaign was talking about how, as council president, I would not allow the issue of black or white, East Side or West Side to be the ruling politics inside of council.

CM: Your father was black and your mother Italian. Do you think that family background gives you any insights that might help you bring the city together?

FJ: Well, I can't hate my mother or my father, can I?

CM: When Stephanie Tubbs Jones introduced you at your victory party, she said, "I don't need him to inspire me. God does that for me."

FJ: I'm glad for that!

CM: But what would you say to people who have a different view of the mayor's role than the congresswoman — who think inspiring people is part of your job?

FJ: What I bring is at least a belief that things are going to be different, and that they're going to be different in a way that inspires people to want to participate.

There are thousands of people in Greater Cleveland who'd love to help the city out, but they're not going to do it in the current environment. So if they're inspired to lend their talents and resources and energy to helping Cleveland, I think that's the kind of inspiration that I as mayor will help bring, as opposed to looking for somebody you'd walk off the cliff for.

CM: And you're going to do that by?

FJ: Being myself, doing what I've been doing. I deal openly and honestly with people. I keep my word, I ask for help where needed and I show gratitude.

CM: You've talked about being in favor of a regional economic development authority.

FJ: What I said was, I would be willing to have the discussion.

CM: What should a regional economic development authority do?

FJ: It should help develop regional economic development packages, so we don't steal from each other internally, in terms of tax abatement and lower interest loans and grants. It should focus on creating the region as a competitor on a national and international basis — again, getting away from internal competition.

If we've got a regional authority, what do we [the city] get out of it? If part of that, as an example, is that we have the ability to turn brownfields into clean, marketable land, it begins to make some sense.

CM: Besides hiring a new CEO, what specific changes will you make in the schools to convince voters to support levies again?

FJ: I can't tell you that for sure, because I do believe it's the CEO and board's job to run the system and be accountable for its success or failure.

We're going to have to do better with the money we've got, because nobody's going to give us any more money. Part of the agenda is to go to the state and whup on them to make them do what they're supposed to do. But in the meantime, you've got to operate with what you have, because the taxpayers are not going to give us any more money. That means I have to look at the system itself, how it's functioning, and how's it an impediment to the improvement of education.

CM: What are your first thoughts on what's getting in the way of schools getting better?

FJ: There's a lack of morale. It's dysfunctional. There's a lack of confidence from the public, lack of morale from the teachers, staff, students, parents.

The first thing you have to do is create the intangible thing, which is [the sense] that things are going to get better, and some sense of hope for the future. Simultaneously, there's certain little things you've got to do: picking the right CEO, having someone [else] who can deal with the bureaucracy of the school system, so the CEO can focus on the educational side and then begin to make some recommendations as to how to retool the system itself.

CM: Is there a limit to how much you would pay the CEO?

FJ: All I want is for the public and for me to know that I get what I pay for. So whatever that might be. If we get what we pay for, then I think it's money well-spent. If you don't get what you pay for, it's a waste.

CM: In July, you told me, "This is not an academic exercise. I just have a problem with people who want to look at Cleveland and say what someone else is doing. • [That] does not really address the real need of people and doesn't have a feel for the suffering or the aspirations of people." What's an example of something the Campbell Administration did that struck you as an academic exercise that you won't repeat as mayor?

FJ: Academically, we could talk about how we were the poorest city in the country [in 2003]. And it's mainly because we were unemployed or underemployed. And the solution is, get more jobs.

Then you hold a poverty summit and you go through an academic exercise. What about the jobs?

The Fannie Lewis Law was right on the ground, dealing with the aspirations: "Give me a job!" The law says, in construction [jobs funded by the city, Clevelanders are] guaranteed 20 percent as a floor. That's a very practical thing. I cut to the chase and got to the real problem.

CM: What kind of casino plan do you think would be good for the city?

FJ: If you put a casino here, the notion is that you will stop money from leaving Northeastern Ohio. Why? Because people go to Canada or Detroit and places for gambling.

That implies that if you put one here, you'll stop that money from leaving. I think that's a fallacy. The money goes into the casino, and it goes back to Vegas or New Jersey. We have to figure out a way to keep money here.

Each casino will pay fees. If we allow the fees to go into the [city's] operating budget, we're ruined, because we'll be dependent on it. Imagine if you got $25 [million] to $30 million annually from the casino in terms of fees. What would happen is, you would budget that in, and if they threaten to leave, who's driving the ship? Who's in charge?

That money should be put into a separate pot for economic development that is invested to create jobs that are not tied to gaming. That way, if the casino decides to leave, or we want to put it out, the only revenue we lose is the income tax off its employees.

The ownership structure, I think the more local it is, the better. You have to create an ownership that has the city of Cleveland and its region at heart.

CM: You support building a new convention center. What do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed Mall site and the proposed Tower City site?

FJ: The Mall site [has] pretty much a fixed cost. The Tower City site, they don't have as much of a fixed cost. So that's a benefit to Mall C. Tower City, however, has better connectivity with things: hotels, retail, that kind of stuff. And it's on the water.