Now I’m going to begin by telling you the truth, and the truth is this. I didn’t want to write this story. I have grave misgivings about it. It gives away trade secrets that maybe shouldn’t be let out. It deals with a sensitive subject that I hate to fool with.

How I got into this was that the editor of this magazine and I had lunch a little while back.

“Why don’t you write a piece about why newspapers and magazines never print any good news?” Mr. Roberts said.

(I don’t rush blindly into any assignment. I weigh the considerations first.)

“Who is paying for the lunch?” I asked.

“I am,” said Mr. Roberts.

“Can I have the Number Four with the Hollandaise sauce on it?" I asked.

“You may,” said Mr. Roberts.

“OK, “ I said. “I’ll write it.”

This left only a few minor details to be ironed out.

“Uh, what do you mean, a story about why newspapers and magazines never print any good news?” I said.

“Oh, you know,” said Mr. Roberts. “How we are always getting calls from people complaining about scandal stories and murder stories and exposes. From people asking why we don’t have any nice stories in the newspapers or magazines.”

I felt I was very close to the heart of the matter now. It seemed to me that one more question was necessary, however.

“Well, why don’t we?” I asked.

Mr. Roberts looked as if he had a pain.

“What do you mean, why don’t we?” he said.

“Why don’t we print nice stories?” I said. I knew that if he could answer that question my story would be much easier to write.

“Why,” said Roberts, regarding me kindly, “why, nobody would read them, of course. Take a plane crash, for example. Now everybody would read about a plane crash. But suppose you wrote a story about a plane that didn’t crash? Suppose you wrote a story that said something lake (he squinted his eyes here, composing a lead for his story) … ‘A Pan-American Airways flight carrying 108 passengers landed safely at Heathrow Airport this morning following an uneventful five-hour flight from New York. This happens every day.’

“There,” he said. “Who would care about a story like that?”

“Nobody, probably,” I said.

“You see?” sad Mr. Roberts. “If we printed nice stories, nobody would read them.”

“Well,” I said, “why can’t I just write that in my piece?”

“Because,” said Mr. Roberts, “that’s a rotten reason.”

OK then, let's try a different tack. Why don’t newspapers and magazines ever print any good news? They do. They do it all the time. Newspapers, in fact, go out of their way to write happy stories. And sometimes they go out of their way to make stories happy whether they are happy or not.

I know this because I used to write such happy stories. I wrote a lot of them for Louie Clifford, late city editor of the Press. I loved Louie Clifford more than I will ever again love anyone I work for. I thought he was a great man and I still think so. What little I know about news papering, he taught me. And one of the things he taught me was that certain kinds of stories are happy stories and should never be allowed to be anything else. Hundred-year-old lady stories, for example.

One lazy summer day, a good many summers ago, Clifford beckoned me with a crook of his finger. He asked me to go, with a photographer, to a nursing home where a lady was celebrating her hundredth birthday. I did not relish this prospect. I had become somewhat of a veteran when it came to hundred-ear-old lady stories. I had a few of them under my belt already — every time we heard about one we covered it. I knew the pitfalls involved with such assignments.

In the first place, your average hundred-year-old lady is as deaf as a stone post. This makes interviewing her difficult. And interviewing her is already difficult enough because there isn’t really all that much to ask her. The rules for interviewing hundred-year-old ladies used to be that you first asked on how it felt to be 100. If you got through that all right, you asked her to what she attributed her long life. If you got past that point you could ask her anything. Whether she thought electric lights were here to stay, for example.

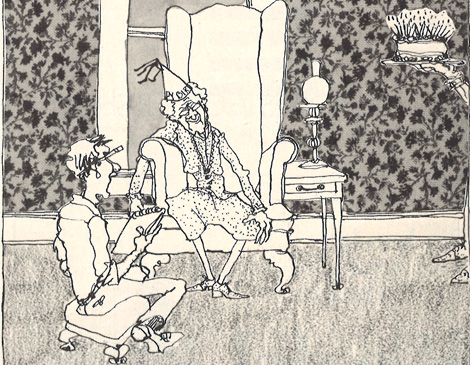

But you rarely got that far. Usually what would happen would be you would arrive at the hundred-year-old lady’s house to find that somebody had propped her up in a corner of a chair in the living room. The somebody was often her daughter who was on hand to act as your interpreter. And this was no bargain because the daughter of a hundred-year-old lady is often 80-years-old herself and she may be as deaf as a stone post.

Well, the hundred-year-old lady may be glaring at you from the corner of her chair like a turtle. There was nothing personal in it but it was disconcerting. You would put on a toothy smile.

“Happy Birthday!!!” you would bellow.

The hundred-year-old lady would ignore this.

“How does it feel to be 100 years old?” you would say.

“Momma darling, he says how does it feel to be one hundred years old?” the 80-year-old daughter would say.

Sometimes the hundred-year-old lady would make a sound, and if you were really lucky, the 80-year-old daughter would turn to you and say:

“She feels great.”

And you would dutifully write “great” down on your notepad.

But sometimes the 80-year-old daughter wasn’t hip to your game. Sometimes she would turn around and say something like:

“I don’t think she knows you are here. She hasn’t said anything to me for seven weeks and the last time she said anything to me what she said was, ‘When are the leaves going to ride in the wagons, George?’”

If this happened, you were in a bit of journalistic difficulty. Because Louie Clifford was back there on that city desk waiting for a nice happy hundred-year-old lady story

And the photographer would be nervous too, because Louie Clifford would also be waiting for a nice happy hundred-year-old lad picture to go with the story.

“Jesus!” the photographer would say. “See if you can sort of twist her around in the chair so’s I can get her from the side, huh? She don’t look too hot from the front.”

So then you would start to swear and think as hard as you could.

“Assuming,” you would say to the 80-year-old daughter, “that mother is remembering the events of her life what events is she likely to be remembering?”

And if you were lucky, you might be able to come back to the office and sit down and write a piece which reads something like this:

Mrs. Charles Glutz’s life has lasted 100 years. There is so much to remember and today Mrs. Glutz remembered — privately, quietly, a slight smile on her lips, in the home of her daughter, Mrs. Elsie Zonk.

Behind her china-blue eyes, the events reeled. The journey to America from a foreign land. Her marriage, the birth of her three children. The death of two of them and her husband’s passing.

There is too much to tell it all here. There is pain and there is love. A century of both. What was it like? Mrs. Glutz smiled and murmured one word:

“Great,” she said.

Now that is the way you write a happy hundred-year-old lady story. At least the way you wrote one for Louie Clifford.

Well, on the day I started to tell you about, Clifford sent me out with a photographer to capture another century dame. This one was in a nursing home and I didn’t like the sound of that. We got to the home and were ushered into the hundred-year-old lady’s room. As usual, she was hunched in a corner of an armchair. When we walked in, she turned her head and glared at us.

“What do you want?” she snapped. “Go away!”

I was delighted. This was about my fifth hundred-year-old lady interview and at last I had one that could really talk.

“Happy Birthday!” I said.

“Bah!” said the hundred-year-old lady.

“How does it feel to be 100 year old?” I asked.

“How does it feel?” the hundred-year-old lady said. “How does it feel? I’ll tell you how it feels. It feels terrible.

“Everybody I ever cared about … everybody who ever cared about me is dead. The ones who are left never come.

“Each day I ask myself one question. Why can’t I die? Why do I live so long? I want to die but I can’t die. I live and I live. Why? You tell me. Why?”

I stood blinking in the face of this barrage. The photographer was snapping pictures like crazy and grinning broadly. This was the most animated hundred-year-old lady that had ever come his way. As we watched she began to sob — sob with rage that she was still alive in a world where everything meaningful had died for her.

On the way back in the car we were both pretty excited. Here was a hundred-year-old lady story with a difference. One that was really moving. One that seemed to make a social comment. We chattered about it awhile. Then we fell silent. Each of us was thinking his own thoughts.

“I got a great picture of her bawling,” the photographer said. Then he stopped talking and gazed ahead at the road, thoughtfully.

“Uh…,” I said. “I guess Louie will really like this, huh?”

“Well…,” said the photographer.

“I mean the pathos … the cruelty … the stark humanity, I guess Louie will really dig it. Don’t you think?”

“Tell you what, said the photographer. “I’ll, er, print one head shot of her. You want more, you tell me after you talk to him.”

So I went back and wrote the story just the way it had been. I took it over and put it next to Clifford’s elbow. Then I went back to my desk and peeked at him out of the corner of my eye.

He picked up my copy and read it, turning the pages slowly. When he liked things, he would sometimes smile slightly. This time, he didn’t smile. When he hated things, he would sometimes wrinkle his forehead and puff out his lips. This time, he didn’t wrinkle and he didn’t puff. He just read it. Then he put it down. Then he looked at me. He looked at me for about 20 seconds. Then he crooked his finger at me. I walked over and stood next to him. We both stared down at the story.

“What,” he said softly, “is this?”

“Hunnerd-year-old lady you sent me on,” I said.

He peered up at me. He had china-blue eyes, too. Only his, when he wanted them to, could freeze the balls off an Eskimo.

“Is what you wanted me to do is put this into the newspaper?” he inquired politely.

“Well…,” I said. I stopped there. I didn’t want to be too argumentative.

Clifford shook his head sadly. He shifted his gaze back down to the copy. If the edges of the paper had curled and blackened and the whole story had burst into flame I would not have been surprised.

“It’s terrible, isn’t it?” he said mournfully. He could have meant the hundred-year-old lady’s plight. Or he could have meant my rendition of it. Or he could have meant both.

He looked up at me again, the smallest flicker of hope in his eyes.

“I don’t suppose there was a cake or anything?” he said.

“Uh … I didn’t ask, Louie. I mean, it just didn’t seem very important after the way she was going on and all, I mean, you know, usually you think of 100-years-old as some sort of triumphant happy time, and in this case it wasn’t and I just thought it would be an interesting chance to tell this story because it isn’t the kind of story you expect on somebody’s hundredth birthday …”

He listened to me patiently and while he did, his hand, with my story in it, was moving. It was moving way inside into the deep recesses of yellow legal pad he had on his desk. When a story went in there, it never came out again. Nobody ever saw it again. If you were smart, you never mentioned it again.

“Well,” he said, not unkindly, “I guess it just didn’t work out.”

“No” I said.

“Thank you,” he said.

“You’re welcome,” I said.

And I went back to my desk and sat down.

He never game me another hundred-year-old lady story after that one. Maybe he thought the experience had ruined me as a hundred-year-old lady reporter. Maybe too he thought I had learned all I there was to learn about hundred-year-old lady stories and it was time for me to learn about something else now.

I suppose if he had been a different kind of man, he might have bawled me out. “Listen, stupid,” he might have said, “why do you think I bother sending people out to get these hundred-year-old lady stories anyway? I do it because they make people feel good. They make the lady’s family feel good. They make people that read about her feel good. They make a nice contrast to all the bums and pimps and murderers and wars and creeps and crooked politicians we write about. Hundred-year-old lady stories are supposed to be nice stories. They are supposed to give the illusion there is a little nice in the world. If you had any brains, you’d have been able to figure that out yourself.” He might have said that, if he had been a different kind of man.

But he wasn’t. He probably wanted me to figure that out for myself. And I did. And I vowed never to fool around again with “Firemen-rescue-cat-up-in-tree” stories or “Local-4H-club-milks-for-muscular-dystrophy” stories or “Bulgarian-twin-sisters-reunited-after-70-years” stories or any of the other kind of happy stories the newspapers are full of that you never notice.

Because you never read them.

Because you would rather read bad news stories for whatever rotten reasons of your own.

Which is why you think newspapers and magazines never print any good news.

Next question.

This column originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's January 1979 issue.