Hector Vega gets Hector Vega.

But, then again, what's not to get? His archival prints are easily recognizable: colorful, geometric images, often of Cleveland cityscapes, on dense foamboard, hand-cut into pieces and mounted in five layers to create a three-dimensional effect.

Too commercial for some — but at his newly opened Artefino Art Gallery Cafe, the Vegas are confined to the walls near the entrance. Works by other artists have a more prominent place in the retro coffee shop/gallery, hanging from the walls and ceiling so diners at the little white tables-for-two can contemplate their meaning as they sip a latte or fruit smoothie.

Rarely will you find grungy, dark, conceptual or philosophical art here. That's not what he wants to get into, Vega says. Instead, his motives for the venture are as vibrant, happy and full of energy as the works he creates and sells. "It's nice to help other artists," the 41-year-old says as he sits at a table near the back of the gallery. "That was my whole intent."

If only Hector Vega were that simple. Artefino, in the 1900 block of Superior Avenue, is the latest hue in the big box of crayons he calls his life. The man who commands as much as $25,000 for a large original painted on commission — the only originals he does anymore — also holds down a full-time job as a graphic-design manager in the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority's construction department and involves himself in a number of civic activities.

"He has done something that not a lot of people can do: He has combined his business savvy and entrepreneurial skills with his creative talent," says Debora Erksa, director of ArtMetro, a downtown gallery that sold Vega's work for three years. To advance his multifaceted career, Vega says he works days that begin at 5 a.m. and sometimes end at 1 or 2 a.m. Maintaining the drive to do that, however, hasn't been a problem.

"All I have to do is remember my past, and that engine kicks in," he says. "That's my fire."

Hector Vega believes the balanced, linear composition of his work was born out of the chaos of his formative years, a first bid for control during a period so turbulent that sequences of important events and the dates of milestones — the year he graduated from high school, for example — are jumbled and blurred in his memory.

"I don't remember much of my childhood," admits the artist, who is able to discuss, even laugh and joke about, his upbringing without a trace of bitterness. "It was like putting a movie on fast-forward."

Vega certainly remembers arriving in Cleveland with his mother Maria and three siblings when he was 8 years old. Who wouldn't? Maria moved the family from their hometown of Gurabo, in the mountainous center of Puerto Rico, to the United States to get away from her husband.

"He was a criminal," Vega says matter-of-factly of his father, Hector Sr., whose activities included drug trafficking and prostitution.

Maria found work as a seamstress and settled into an apartment on the near West Side, a few blocks from where her aunt and grandmother lived. But any attempt at leading a normal life ended when Hector Sr. followed the family to Cleveland. Vega recalls moving from apartment to apartment, even to Puerto Rico and back again, in repeated attempts to elude the man.

"He would just show up out of the blue, drunk, crazy out of his mind sometimes," he says. That ended about three years later. Vega guesses he was 11 years old when Hector Sr. was shot to death and a homesick Maria moved her children back to Puerto Rico.

But young Hector was tired of life on the move. So, with money saved from doing odd jobs, he ran away from home and back to Cleveland. "Cleveland was my home," he says.

The boy falsified the necessary paperwork to get a full-time job in the produce department at the former Pick-n-Pay supermarket on West 25th Street. (He later transferred to the West 65th Street store.) He worked nights and weekends and rented a tiny house in the Detroit-Shoreway area, where he lived without electricity and gas until his mother and siblings rejoined him two years later.

"In Puerto Rico, we lived in the mountains, and we didn't have any electricity or heat," he explains, and then laughs at his own ignorance. "I honestly thought that was just the way it was."

Although the teen-ager attended Thomas Jefferson Middle School and Lincoln West High School in his mother's absence, he was a less-than-enthusiastic student, in part because he suffered from dyslexia. "I learned enough to get by on, but I didn't care about anything, growing up the way we did," Vega says. "There was nothing to really aspire to, to look forward to." That began to change, however, when he won first prize in a national art competition after an art instructor entered one of his paintings without his knowledge.

"He had to push me to produce that art. I just didn't take anything seriously back then," Vega says. "But that really got my attention."

The recognition prompted Hector to enroll in a couple of graphic-design courses at the Virginia Marti College of Fashion & Arts after he graduated from high school. He also began participating in local art festivals such as the Clifton Artfest, where he sold secondhand ties decorated with well-known Cleveland landmarks rendered in acrylic paint. "People were buying them like there was no tomorrow!" he exclaims, still excited by the memory.

But he didn't quit his job at the supermarket until his late 20s, when he was hired as a graphic designer at Cleveland City Hall on the recommendation of Miriam Ortiz Rush, publisher of the now-defunct Latino newspaper El Nuevo Dia. Rush says she met the young artist in 1989 through her cousin, a friend of Vega's who suggested him as a business partner — unpaid volunteer, as Vega puts it — to help lay out and design the paper.

"He was a kind, compassionate, caring person who was committed to helping advance the Latino community," remembers Rush, now personal bailiff for Cleveland Municipal Housing Court Judge Raymond L. Pianka. As for helping him get the job at City Hall, "his talent and perseverance are what helped him," she insists.

For the first time, Vega was surrounded by people, many of them influential, who bought nice homes and laid plans to advance careers and start businesses rather than subsist from day to day as he and his family and friends did. "When you're in the inner city," he says, "that's all you know."

Rush, a board member of the Detroit-Shoreway Community Development Organization at the time, encouraged Vega to scrape together a down payment on a condominium in the neighborhood, a purchase that later served as equity in financing Artefino.

Eventually, he left City Hall for a gig as an art instructor at the Cudell Fine Arts Recreation Center on Detroit Road and his current employment at CMHA. "It just completely changed my life," he says of the period.

During this time, Vega also became involved in volunteerism and philanthropy, interests he credits Rush and Beachwood attorney Lewis Zipkin, whom he met at a Halloween party thrown by a colleague, with sparking.

"I saw that people like Miriam and Lew were always active in the community," he explains. "At first, I wondered, Why do you do this with your free time? But you can see it in their faces: They love to do what they're doing to help people. I said to myself, Hey, I want to do that."

He began by donating small works of art to nonprofit fund-raising auctions. Over the years, his contributions increased from those Clifton Artfest ties to original works promoting organizations and events as diverse as the Tri-C JazzFest and Ohio City Home Tour. He donated three images to the Cleveland Sight Center for use on its greeting cards and currently sits on the boards of the Detroit-Shoreway Community Development Organization and El Barrio, a Hispanic social-service agency.

Tom Schorgl, president of Community Partnership for Arts & Culture, first met Vega in the late 1990s, during an interview about the arts community's strengths and weaknesses for CPAC's first strategic plan for Northeast Ohio. Three years ago, Vega worked on the focus group that created "The Artist as Entrepreneur" program, which teaches business skills to artists.

"He's a person who truly is interested, cares about and walks the talk when it comes to trying to make Cleveland a better place to live," says Schorgl.

That includes going beyond the typical artist contribution for GuitarMania, a project that benefits United Way Services and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. In 2002, Vega sat on the project's advisory board and transformed a 10-foot-tall fiberglass Fender Stratocaster into a work that was auctioned at the museum. For this year's GuitarMania "Encore in 2004," not only did he produce "The Art of Flight," sponsored by Continental Airlines, and "Revitalizing Cleveland," sponsored by National City Bank — but he also shelled out $7,500 from the Artefino advertising budget to sponsor a guitar. "Cleveland Rockin' Roller," a red-metallic guitar-turned-chopper by Gregory Glueck, is on display outside the gallery entrance. Vega also reviewed proposals for guitars submitted by local artists (minus his own) and sat on a special-events subcommittee. It was his idea to auction off the drawings artists submitted to the GuitarMania jury at a gallery event Oct. 7 and turn over 25 percent of each winning bid to the respective artist.

"Many of the artists did their guitars — that was a great contribution," says Michael Benz of United Way Services. "But Hector has been involved — a lot of time, a lot of ideas. And he never wants anything back for it."

The payoff, of course, has been lots of exposure for the artist and his art. Vega, who counts networking among the most valuable skills he learned at City Hall, used the free tickets he received to attend the auction fund-raisers. "People who didn't end up with the piece would give me their cards and asked me to call them," he says. But he insists that his donations and volunteer efforts, both past and present, are rooted in altruism.

"I don't go to church a lot — hardly ever," he confesses. "But it gets back to having faith in a greater power, believing in some type of karma. If your intentions are good, it all comes back."

It wasn't until 1994 that Vega began selling his paintings in for-profit art galleries — something he'd never seen or heard of in his inner-city environs. Avery Wieder, owner of Chelsea Galleries in Woodmere, first approached him at a group show of inner-city artists. Wieder remembers being struck by Vega's cityscapes.

"Cleveland scenes [by other artists] were pretty standard," Wieder explains. "They were nice enough, but there wasn't any real passion to them. Hector had this cubist edge to the work. The colors were vibrant. The style translated into other subjects as well, but the cityscapes in particular, I thought, Wow! They just grabbed me."

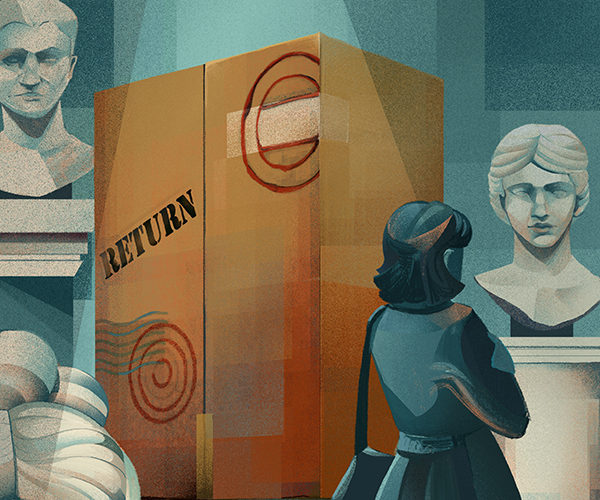

Vega began selling reproductions of original paintings and turning out commissioned works for businesses and private buyers. "Seeing a real gallery in the suburbs opened my eyes up to, Wow, this could be a whole business!" he remembers. Even as he went on to sell work through other galleries, he began laying plans to open a business of his own, "a user-friendly art gallery" where customers could browse and buy without any pressure whatsoever.

"A lot of galleries are too pretentious," he claims. "If you don't make a lot of money, you're not welcome there. I wanted to design [a gallery] to be the opposite: Everybody is welcome."

The idea to combine a gallery and cafe was inspired by Monica Lukez, a pretty, reserved, correspondence-school guidance counselor with a passion for cooking. Vega met her at the Tremont Art Festival a little more than four years ago. "It was love at first sight," he says. The two were married July 4 on the tiny island of Vieques, off the coast of Puerto Rico.

After looking at spots in downtown Cleveland and the Tremont and Murray Hill neighborhoods, Vega settled on a retail space in the Tower Press Building. The structure, which touts its live/work spaces to artists, provided both a built-in clientele and a wealth of potential suppliers. "I think this is an up-and-coming neighborhood," he adds. "Location-wise, it was ideal for what I wanted to do." Artefino opened to the public June 14 with a full-time manager and half-dozen mostly part-time employees.

The transition from artist to business owner, however, was not without its challenges. "The closest I came to being prepared was having good credit and good financial records," he admits. "In terms of knowledge, I was not prepared in any way."

Longer-than-expected lease negotiations — involving common-area maintenance fees, reserved parking spaces for patrons, employee access to the onsite gym, et cetera — and obtaining financing delayed the cafe's opening a year.

"I felt like it was an iron-man test that the bank was putting me through," he jokes. "It was psychological torture. If you survive it, then they say, •OK, he'll make a good businessman!' "

Erksa says she believes the cafe does for the gallery what coffee bars did for bookstores: lure people inside who might normally walk past the door. But not everyone is thrilled with Vega's attempt to combine sculpture and sandwiches, jewelry and java. "A couple of gallery owners called what I'm doing blasphemy," he says, although he won't mention anyone by name. "A lot of people say I'm too commercial." It's a charge repeated off the record by at least one member of the arts community.

Representatives of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland both declined requests for comment on Vega's work, explaining that no one on their respective staffs knew enough about it to do so — true perhaps, but interesting nonetheless.

"What does it say about MOCA that they cannot comment on one of the local arts scene's most commercially successful artists, good or bad? It tells me they're simply not interested," Wieder says. "What appeals to the elite rarely appeals to the masses. And, unfortunately, art is an elitist kind of an area."

Vega, for his part, doesn't seem too concerned about the lack of recognition and support as he locks up Artefino for the night. He's too busy thinking about his plans for the future: the line of greeting cards, ties and mugs he's developing, upcoming exhibits for the gallery, the wine bar/gallery he'd like to open someday.

"The masses are going to determine whether I make it or not," he declares. "The moment people decide not to buy my art, then I'll know I'm doing something wrong."