10 Cent Beer Night: An Oral History of Cleveland Baseball's Most Infamous Night

by Vince Guerrieri | May. 29, 2024 | 9:00 AM

Paul Tepley Collection/Diamond Images/Getty Images, Courtesy Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library Special Collections, Courtesy Cuyahoga County Public Library

“Any Cleveland police car not on assignment respond to Cleveland Stadium for a riot.”

Cleveland police officer Bill Leonard had just pulled out of the Sixth District Jail sally port on June 4, 1974, when that call came over his radio.

It was a full moon that night and temperatures were hovering in the 70s. Leonard came west on the Shoreway, exiting at East Ninth Street.

Two naked women ran in front of his car.

“I thought, ‘Oh, it’s THAT kind of a riot,’” he says.

It was a fraught time in Cleveland's history. The city was less than a decade removed from a riot in Hough and a shootout in Glenville. Gangland bombings were increasing, and a mob war was on the horizon. And the Indians, the class of the American League in the early 1950s, had spent most of the ensuing 20 years pondering a move out of town.

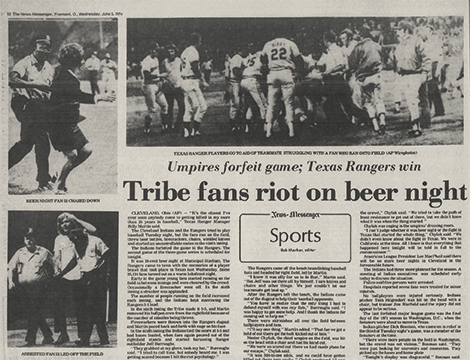

(Cleveland State University. Michael Schwartz Library. Special Collections)

That Tuesday night was a perfect stew of bad vibes, bad blood and copious amounts of beer.

High in the press box at Cleveland Stadium, Randy Galloway was covering the game for the Dallas Morning News. Below him, it was the bottom of the ninth and everyone was loaded. It was 10-cent beer night, and a crowd of drunks was on the field, pushing, shoving and generally misbehaving.

“I wasn’t concerned, but the Cleveland PR guy said, ‘Lock the damn door and nobody gets in,’” Galloway recalls. “I thought, now we have something interesting going on.”

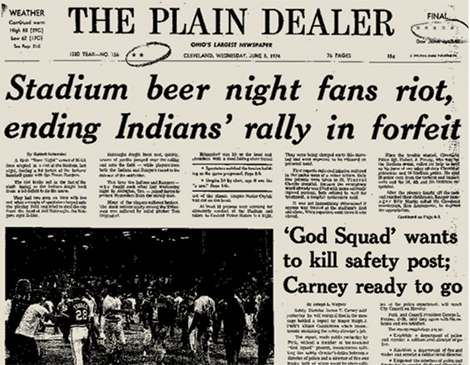

What appeared to be an Indians ninth-inning comeback against the Texas Rangers instead turned into a forfeit loss. The listed crowd of 25,134 drank an outsized number of beers (an estimated 60,000 cups) and did an outsized amount of damage.

The game was originally regarded as a disgrace. But it’s become a part of local legend, exemplifying the ethos summed up by a T-shirt popular in the 1970s: “Cleveland: You’ve Got To Be Tough.”

“I was witnessing history,” Galloway says. “I didn’t realize it at the time. The story just lives on in baseball lore.

“Of everything I’ve ever witnessed, that’s in my top five. Maybe my top three. It was one damn sight.”

TOM BONDA: My father (Indians owner Ted Bonda) and his group were struggling to get people to the games. We used to sit in the old Stadium Club and literally count the people coming over the West Third Street Bridge.

CARL FAZIO (DIRECTOR OF SALES AND MARKETING FOR THE INDIANS): It was a great challenge and a great opportunity. I believed in the Indians and believed in Cleveland.

We were going to leave no stone unturned, and my approach in Year One was that we were going to try everything, be aggressive and figure out what works and what doesn’t work and then we’ll know what to do in ensuing years.

BONDA: We tried everything. We had the Great Wallenda walk across the stadium on a tightrope. I was actually up there. It was scary being on the roof. We brought in the King and his Court, a softball team.

MILT WILCOX (INDIANS PITCHER): They had Evel Knievel once. I actually helped him start his motorcycle. It had a kick starter, and he had been in so many wrecks he couldn’t do it himself.

BONDA: I’d come back to Cleveland after Arizona State and moved into Park Center. We were trying to get people Downtown, and we’d sell beer for 10 cents at what we called parties at the park. I actually got really good at changing beer taps. I told my father we were doing so well, why not have a 10-cent beer night at the stadium?

SUGGESTED: Cleveland's 50 Most Important Moments of the Past 50 Years

It wasn’t an outlandish idea. Since the 1960s, beer nights had become a popular event for major-league and minor-league teams. The Minnesota Twins and Houston Astros had previously done them, and they’d become a regular part of the Milwaukee Brewers’ promotional schedule. (One of them, in 1971, led to a series of fights inside the stadium; of course, nobody remembers that one.) The Indians had hosted several before the 1974 season, and that year they put four 10-cent beer nights (as opposed to the regular price of 65 cents) on the promotional schedule, with the first scheduled for June 4, 1974, against the Rangers. A week before that, the two teams met in Texas.

(Cleveland State University. Michael Schwartz Library. Special Collections)

GALLOWAY: That entire series, the teams were jawing back and forth with each other.

WILCOX: Gaylord Perry pitched the first game of the series in Texas, and I believe Lenny Randle got a couple hits off him. Gaylord ended up winning the game, and Randle popped off in the paper and said he was washed up.

DICK BOSMAN (INDIANS PITCHER): Lenny Randle said Gaylord wouldn’t be able to beat anybody without the spitball.

WILCOX: Gaylord saw me before the game and said, “If I was pitching tonight, Lenny Randle would go down all three times he came up. Not hit him, but knock him down.” And he looked at me and winked, so I knew what he meant.

The first pitch I threw was about two feet behind Randle. I didn’t really know how to brush guys back in those days. It wasn’t bad blood, it was just the way we played then.

BOSMAN: Next pitch, Lenny drops a bunt and Milt goes to cover first, and Lenny just low-bridged him and down they go and we’ve got a pretty good Donnybrook out there.

MIKE HARGROVE (RANGERS FIRST BASEMAN): Lenny just knocked him ass over teakettle.

FAZIO: That hit would make any NFL linebacker proud.

GALLOWAY: And then (Indians catcher) John Ellis comes over and he pops Randle, and all hell breaks loose. I’d seen a dozen scuffles or so in three years as a beat man, but I’d never seen a full-scale fight. And this was a fight.

TOM GRIEVE (RANGERS OUTFIELDER): People were actually getting pounded.

HARGROVE: I was in the dugout, so I went out and joined the fun. Usually, baseball fights are a lot of pushing and tugging, but this was knock-down, drag-out.

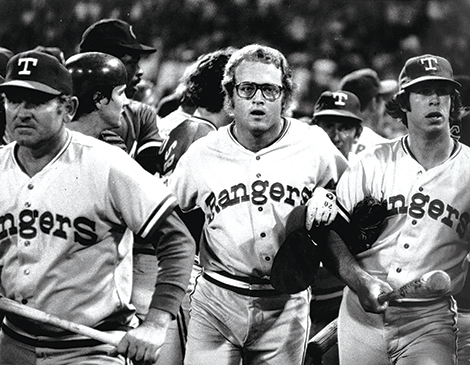

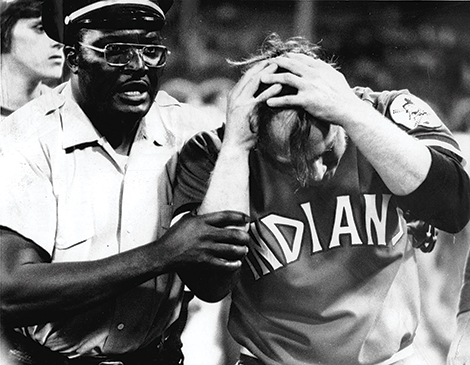

(Paul Tepley Collection/Diamond Images/Getty Images)

GRIEVE: When the Indians went back to the dugout, our fans were screaming at them. (Indians catcher) Dave Duncan got so mad that he jumped up on top of the dugout and tried to go into the stands. They had to pull him back in.

And then after the game, they asked (Rangers manager) Billy Martin if he was concerned about going to Cleveland the next week. He said, “Ahh, nobody goes to the games anyway.”

DAN COUGHLIN (THE PLAIN DEALER WRITER): And then that asshole Pete Franklin worked people up on his radio show all week and said it would be revenge against the Rangers, and that helped inflame the situation. He was good at that.

The Indians and Rangers were meeting again, and both teams were competitive in their respective divisions. The stage was set.

GALLOWAY: We walked over from the Hollenden House, and you could tell. There people headed to the ballpark — and they were pumped up. It wasn’t an atmosphere you were expecting on a Tuesday night in Cleveland against the Rangers.

JOHN ADAMS (THE GUY WITH THE DRUM): People were showing up drunk.

GRIEVE: It was a bigger crowd than normal, but the stadium was so big that even 25,000 didn’t feel like a big crowd.

KEN ASPROMONTE (INDIANS MANAGER): After we saw batting practice, I saw a lot of people in the stands I hadn’t seen before. I said, “Wow, we’ve got a big crowd tonight.” They were already drinking beer.

FAZIO: It was not our typical crowd.

LARRY MCCOY (UMPIRE): We walked to home plate about five minutes before game time, and there was kind of a cloud over home plate. I had no idea what it was. Two of the younger umpires said, “Don’t you know what that is? That’s marijuana.”

BOSMAN: You could get high just by breathing deep.

COUGHLIN: Every half-inning something was going on. It was stuff we’d never ever seen at a baseball game at any ballpark.

HARGROVE: Between innings, people ran across the field. The first time, there were a couple people. The next inning there would be five. Then there would be 10. And then a lot of people. And when I say a lot, I mean a lot.

(Courtesy Cuyahoga County Public Library)

WILCOX: Nobody was stopping them, and the fans were having more and more beer.

GALLOWAY: Some of it was just flat-out funny. We had a father and son run out and moon the crowd.

JIM CLARK (A THEN 19-YEAR-OLD FAN): There was a woman dancing on the dugout. She was topless for a bit. She tried to kiss (umpire) Nestor Chylak.

GRIEVE: They couldn’t get her off the field. She probably weighed about 250 pounds, so they couldn’t pick her up. That was kind of harmless, but I think it was around then that we started to think, “If this is going on early, who knows what’s going to happen next.”

COUGHLIN: Streaking was popular in those days. This kid ran on the field stark naked. He was running along the outfield fence, but he couldn’t see what was going on on the other side of the fence, where the police were running alongside of him. Finally, he decides to climb over the fence, and police were waiting for him with a huge garbage bag. He gets over the fence, into the bag and they lugged him off. And the fans cheered.

HARGROVE: I think I got four pounds of hot dogs thrown at me that night.

SUGGESTED: 1974: Cheap Beers Cause Mayhem

BUDDY BELL (INDIANS THIRD BASEMAN): I was on the DL that night, so I was actually sitting upstairs watching the game. I had a great view. I’m looking down into the dugouts, and the players are yelling at the fans and the fans are throwing stuff into the dugout.

COUGHLIN: Fans were throwing firecrackers from the upper deck. By the middle of the game, things were starting to get out of hand.

WILCOX: You could tell every inning that things were getting hairier.

CLARK: In the fourth inning, (Rangers starting pitcher) Fergie Jenkins got hit and they were yelling, “Hit him again! Hit him again!” I thought, Wow, the alcohol is talking early.

LES FLAKE (CLEVELAND’S FAMOUS BEER GUY): I had started selling hot dogs for the Indians that season. You couldn’t sell beer until you were 19. I was down the third-base line, and I think it was ’round 9 o’clock that I said, “I gotta get out of here.”

JIM SUNDBERG (RANGERS CATCHER): I was in the on-deck circle in the sixth inning, and I was looking around. I was a little paranoid, and I saw this thing come from out of the upper deck. It was a bottle in a paper cup. It was escalating as people got drunker.

CLARK: And Billy Martin was blowing kisses to fans from the third-base dugout.

FAZIO: I heard a guy on the radio say later, “I brought a couple batteries and a golf ball to throw at Billy Martin.”

HARGROVE: I had an empty gallon jug of wine land about 10 feet away from me. I kicked it off the field toward the railing, thinking the grounds crew would get it, but a fan grabbed it and went back into the stands with it. That’s the first time I felt really uneasy, because I felt like it was going to come back at me again.

KEN SANDERS (INDIANS PITCHER): We got the wives out of the stands, I think, in the seventh inning, and got them into the locker room. We brought the bullpen into the dugout. Something was brewing.

(Cleveland State University. Michael Schwartz Library. Special Collections.)

The Indians were trailing 5-3 going into the bottom of the ninth. George Hendrick doubled to lead off the inning, and then Aspromonte called for three straight pinch hitters: Ed Crosby, Rusty Torres and Alan Ashby. All three singled.

ADAMS: We were about to win that game.

CLARK: John Lowenstein hit a sacrifice fly to score Crosby and tie the game. The place was just going berserk.

SUNDBERG: We were going to lose that game. They had the winning run on base.

GALLOWAY: The crowd was going nuts. I don’t think anyone had run on the field in a while. We look out in right field, and here comes a fan. He approaches Jeff Burroughs in right field, and I thought, He shouldn’t do that. Players are going to react. He reached for Burroughs’ hat, Jeff pushed at him. The kid went back and Jeff fell down.

BELL: When I saw Jeff throw a punch, I left and made my way down. I figured it would be settled by the time I got down there. I got down there, and there were people everywhere. They weren’t attacking anyone or anything, but it was like one of those old science fiction movies where aliens invade and everyone’s running around.

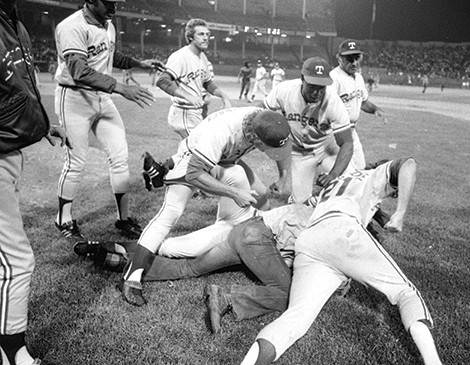

BOSMAN: Billy Martin led the charge of the light brigade out of the dugout and all hell broke loose. The field was just full of people.

WILCOX: They had bats and were wearing their helmets. It looked like a cavalry charge.

COUGHLIN: From the dugout, it looked like Burroughs had been knocked down, so Billy Martin and the Rangers came out to rescue Burroughs, who’s in the middle of a big crowd in right field. That’s when it really exploded. The Indians had to come out and protect the Rangers from our fans.

ASPROMONTE: I said, “We gotta go help Billy.” We figured his 25 and my 25 could take care of it. The people were on the field swinging like hell, but mostly missing because they didn’t know where they were.

GALLOWAY: When the Indians came out of the dugout with bats, I thought, “Oh my God. Are both teams going to go at each other?” The Indians were coming out to help the Rangers, who were now surrounded by at least a couple hundred fans with more coming all the time.

SUNDBERG: We had Custer’s last stand in right field. We were surrounded by fans and we were in a little circle and the Indians players came and joined us, and we gradually made our way back to the dugout.

There was this big guy who was threatening to kick my ass, and Dave Duncan — who was on the Indians — tackled him and before I knew it, Billy Martin was kicking him in the face.

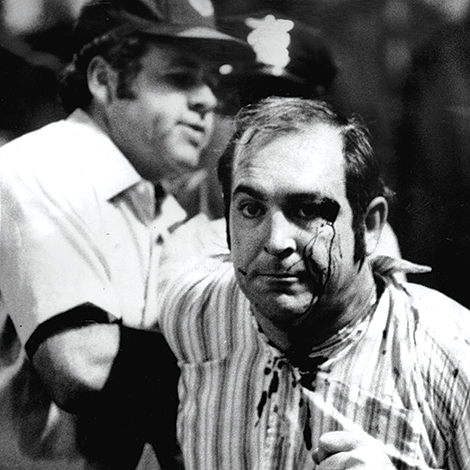

SANDERS: (Indians pitcher) Tom Hilgendorf was standing next to me and somebody threw one of those folding chairs and bounced off Hilgendorf’s head.

BELL: Tom was really self-conscious about his combover. And one of the first things I saw was Hilgy holding his head, with his combover hanging down the front of his head. We laugh about the combover, but he could have been seriously hurt.

(Cleveland State University. Michael Schwartz Library. Special Collections)

LEONARD: It was just bedlam. There wasn’t a whole heck of a lot we could do. We tried to contain the crowd. We might have been there about a half-hour, 40 minutes, before things started to calm down.

BOSMAN: You could tell order was not going to be restored. Pretty soon after Hilgy got hit, someone jumped out of the upper deck onto the foul screen and fell through. And we said, “We might as well go to the clubhouse.” So we retreated and sat there. You could hear it roaring out there. Word came down I guess about 45 minutes later that the game was forfeited.

HARGROVE: We got a police escort back to the hotel that night, and we were told to stay in our rooms until noon the next day, so we all went to bed hungry.

GRIEVE: They would have needed 500 security guards to get the field cleared. Nestor Chylak was so mad that we were walking through the tunnel, and he had his face mask and was slamming it on the light bulbs, smashing each one of them. He was just disgusted.

MCCOY: We tried to keep it from being over. Cleveland had been behind all night, and they had the bases loaded with one out. They had a chance to win the ballgame. Nestor made the decision to call the game, and he made the right decision.

COUGHLIN: They couldn’t have resumed the game anyway. There were no bases. People had walked off with all of them.

GALLOWAY: The next day was a new ballgame. The crowd was fine. Everything was calm.

SANDERS: It smelled like beer everywhere.

Clark: We went the next night, and there were 7,000 or 8,000. The crowd was like a recital, very subdued like they had to show folks they could behave.

SUGGESTED: Guardians Manager Stephen Vogt Is Here To Build Upon the Past, Not Change How It’s Done

Mercifully, there were no serious injuries, and only nine people were arrested. But the reaction, as expected, was disgust. Dave Anderson of The New York Times called it “the beer that made Cleveland infamous.” In the New York Daily News, Dick Young said, “They lure people into the park by offering a beer giveaway. So crowds go there to tank up, not to watch baseball. What do the Lords of Baseball expect?” “How utterly stupid,” wrote Wayne Minshew of The Atlanta Constitution. “How insane. How disgusting.”

BONDA: My father thought it was a success. It got more fans than a typical Tuesday night. It’s not making you wealthy. It’s making payroll. My father was summoned to the league office in New York immediately, and he argued like mad that it was a success, and they should be allowed to do it again.

There was one more 10-cent beer night, a month later against the Athletics, and it drew an even bigger crowd than the one in June, for a pitching matchup between a pair of Hall of Famers: Gaylord Perry for the Indians and Catfish Hunter for the A’s. Security was tripled, and fans were limited to two beers at 10 cents. “It was so quiet you could hear the foam breaking down in your cup,” Bob Sudyk wrote in the next day’s Cleveland Press.

(Courtesy Cuyahoga County Public Library)

DUANE KUIPER (A SEPTEMBER CALL-UP FOR THE INDIANS IN 1974): All those guys had stories from that night. They said it was kind of bound to happen.

Everyone talked about it for a long time. There wasn’t one funny story. When you look at it now, it was a recipe for disaster.

There were two legendary forfeits in the 1970s, both because of, essentially, fan riots. One was 10- cent beer night. The other was Disco Demolition Night on July 12, 1979. The Chicago White Sox held a promotion that night where fans would be admitted for 98 cents if they brought a disco album. The albums would be collected and detonated between games of a doubleheader. Comiskey Park was filled beyond its capacity, with crowd estimates as high as 60,000. By then, Milt Wilcox was with the Tigers, the visiting team that night. (Ironically, Chylak, at the time the American League supervisor of umpires, was in the stands that night, as well.)

GRIEVE: 10-cent beer night was a bad idea, but I don’t think anyone knew how bad it could be. I mean, we had it at our ballpark. Disco Demolition Night looked like a bad idea from the minute they came up with it.

WILCOX: We won the first game. I was scheduled to pitch the second game.

They were going to collect the albums, put them in a trailer they had out in the outfield and blow it up. They put in what they said was a small charge of dynamite. Well, it was too big a charge, and it blew a hole in the field. I was out in the outfield warming up, and the concussion almost knocked me down, and people started streaming on the field. It was probably worse than 10-cent beer night. Cops were running on the field, the umpires were trying to get people off and they canceled the second game within a couple minutes. It was actually a little scary.

In the years since, 10-cent beer night has taken on a mythical sheen, and being there has become a badge of honor. NBC News legend Tim Russert, a student at John Carroll University in 1974, said he was there — and had a good time. “I went with two dollars in my pocket,” he says. “You do the math.” Drew Carey talked about how his friends bragged they were there. And eventually, in 2010, local brands started selling T-shirts.

RYAN VESLER (FOUNDER OF HOMAGE): In the early days, we didn’t have a license with MLB, so I tried to tell baseball stories without using the logos. To me, the T-shirt’s a storytelling canvas, and I always try to dig for things in a team’s history.

One of our first products was for the bean brawl game between the Braves and Padres in 1984. We did a shirt for the pine tar game between the Royals and Yankees, and one of the bat burglaries (when Indians reliever Jason Grimsley stole one of outfielder Albert Belle’s bats, which had been confiscated).

We did one for 10-cent beer night, more to celebrate the absurdity of it, and not so much the outcome. It turned into a crazy seller. I think a fan wants something that’s a deep cut, below the surface of your typical logo. It’s a way for a fan to say, “I’m a true fan, and I know the history.”

BELL: We can kind of laugh about it because nobody got seriously hurt.

ADAMS: A lot of people have come up to me since to tell me they were there. Or their friend was there. Or their third cousin from a fourth marriage. There must have been 720,000 people there.

I watched it all unfold in front of me. It was themost bizarre game I’ve ever seen.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Vince Guerrieri

Vince Guerrieri is a sportswriter who's gone straight. He's written for Cleveland Magazine since 2014, and his work has also appeared in publications including Popular Mechanics, POLITICO, Smithsonian, CityLab and Defector.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5