I Walked Across Lake Erie — Alone

by Dave Voelker | Dec. 19, 2022 | 1:00 PM

Dave Voelker

To a novice, a winter walk across frozen Lake Erie to Canada is almost certain death. To a person trained in wilderness skills, it's just a calculated risk— an uncommon sort of trip that might seem foolhardy at first impression, but which becomes more and more feasible with every map, depth chart and weather report that you study. At its narrowest, the lake's width is only 30 miles — a comfortable two-day jaunt if you're in shape. Most years, its surface freezes solid all the way across, to a thickness that will usually support a party of hikers. The biggest danger is that of exposure, since the barren surface offers no escape from the malevolent elements of winter, especially wind. Solve that problem, and you've got the whole thing licked.

I never intended to go alone. Actually, the scheme was concocted by a group of local spelunkers (cave explorers), some of whom I'd accompanied on various caving expeditions over the last ten years. Six of us were to depart from the Catawba peninsula, a few miles west of Sandusky and about 80 miles west of Public Square, before dawn last February 18, a Saturday. We would head almost due north and make the trip on one marathon bite, passing just west of the Bass islands and hitting the Canadian shore near a town called Colchester just after dark. Besides crossing the lake at one of its narrower widths, this route offered another clear advantage: The islands would tend to anchor the ice and minimize shifting, and they would provide refuge should a hasty retreat become necessary.

One crucial question remained unanswered. It had been a cold winter, but could we be sure the lake was frozen all the way across? We assumed that it was, but couldn't swear to it. We would be foolish not to dig up all the information we could find relating to our chances for survival. In fact, I proposed contacting one organization that was bound to know: the U.S. Coast Guard. Without giving the particulars of our crossing (exactly where and when), we could simply admit what we planned to do, and invite them to tell us everything about the lake they thought we should know. It couldn't hurt and it might help.

With that seemingly innocuous suggestion, I hit a nerve. Cavers are most comfortable working under the cloak of anonymity. They're an extremely conscientious bunch, generally showing more respect for a cave than its owner, but countless brushes with uncooperative landowners have taught them to get their way by simply avoiding detection. Though crossing the lake violated no law, they feared that my call would increase our chances of being picked off the ice by a vigilant Coast Guard helicopter, whether we wanted to be rescued or not.

When they learned that I had decided to write an article about our expedition, the spelunkers' dispositions turned even more sour. They didn't want any publicity, even if it was after the fact, and even if their names weren't mentioned. The group stressed that, in the cause of cooperation and coordination, the personal interests of any individual in the group — specifically, mine — should be subject to the approval of the majority. I reluctantly bailed out.

On February 18, they made their crossing as planned. Well, not quite as planned. I had argued that a two-day trip would be a better idea, because 30 miles was too much for six relatively out-of-shape persons to hike in one shot. The last stretch of ice would have to be covered in darkness, which, combined with fatigue, would reduce the safety factor to a dangerous low. Instead of reaching the Ontario shore slightly tired at 7 p.m., they arrived at 11 p.m., totally exhausted. Toward the end, just staying on their feet was a real struggle.

Meanwhile, I hadn't abandoned my own plans for a solo crossing. The spelunkers' qualified success proved that the route was passable; the ice was solid the whole way. Unknown to them, I had already called the Coast Guard before their departure to find out whatever they could tell me about the lake in winter. I half expected a frenzied lecture on ice safety, with a desperate plea to settle for walking across the fountain on Cleveland's Mall. Surprisingly, I found the Coast Guard officers to be concerned and extremely helpful, offering safety tips about ice characteristics and the advantages of certain wind directions. Sure, they discouraged the idea, but they acknowledged they were powerless to prohibit such crossings, and they might as well make sure the participants take as many precautions as possible.

The following week I tried to find at least one other person to go with me, but no one was particularly crazy about the idea. If I was really bent on going, it looked like I would have to go alone. At the outset, when so much was uncertain, I would not even have considered a solo hike, but I had built up my hopes sufficiently that, by then, I could undertake the trip by myself and still feel reasonably secure — even though, by venturing out alone, I was breaking the cardinal rule of outdoor safety. I rationalized it as an inescapable necessity, but the fact is I was secretly relieved not to have to share with anyone an experience that was bound to be at once ennobling and humbling — and profoundly personal. I decided to make the trip the weekend after the first expedition, taking two days to do it.

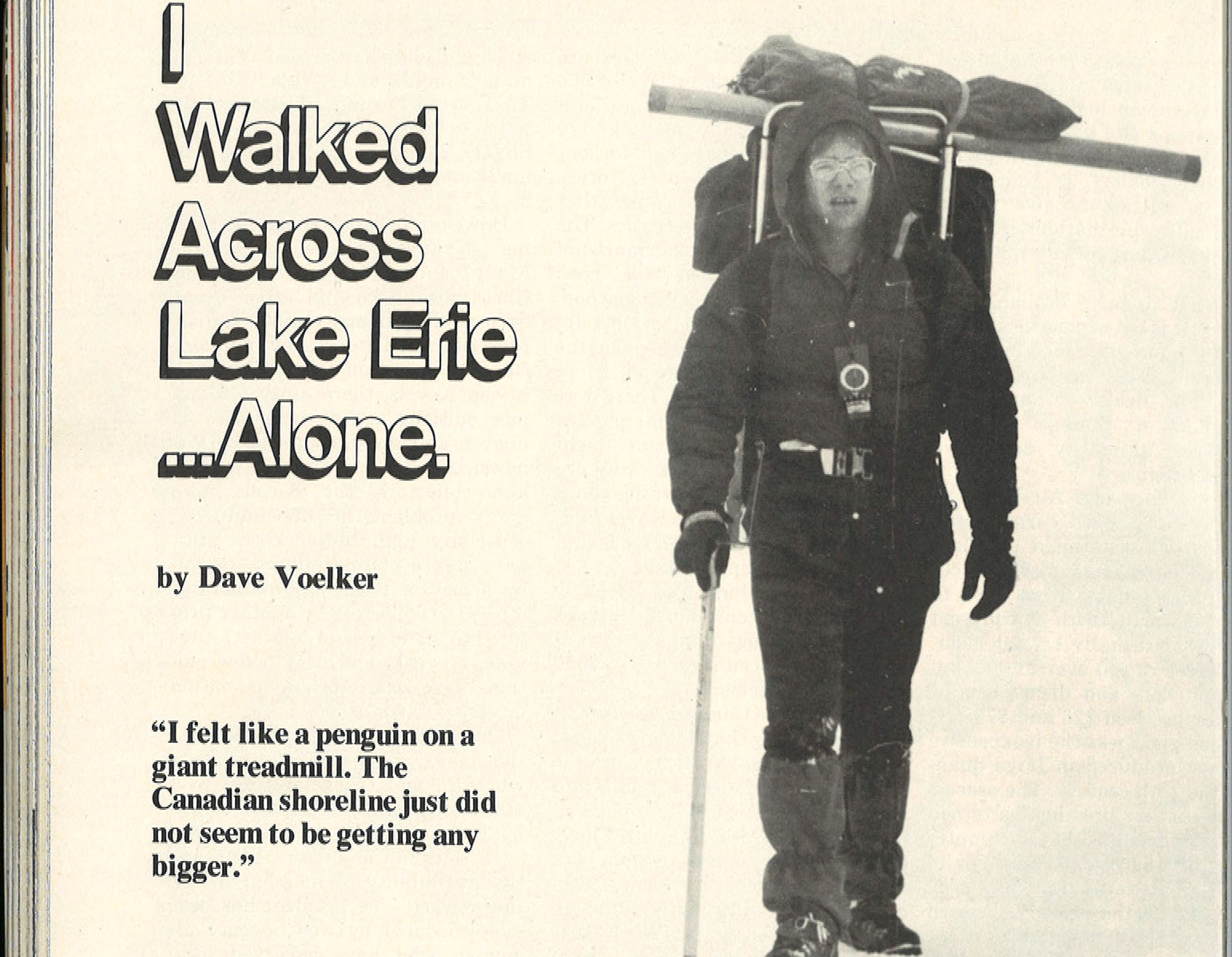

The temperature had been below freezing for over 30 days and promised to stay down there through the weekend. I could look forward to a cold and windy hike. My equipment included a backpack, a tent, a sleeping bag, two large empty water bags placed in the bottom of the pack for flotation, an ice ax (a special ice climbing tool), a red flare and a two-channel walkie-talkie. Total pack weight: about 40 pounds. In addition, I brought my camera and tripod to record my crossing on film. This account is lifted from a mini-journal I kept along the way, expanded when I got home to include observations that numb fingers precluded from recording on the spot.

Saturday, February 25, 1978

8:30 a.m.: Having notified reliable friends to call the Coast Guard if they hadn't heard from me by Monday afternoon, I got up at 5:30 and drove out from my North Royalton home to Catawba. The place was already crawling with ice fishermen, and the only parking spot I could find was at Catawba State Park, on the west side of the peninsula. It occurred to me that there would be no way to verify my crossing; so I asked an incredulous fisherman to sign an affidavit that he saw me head out on the ice. Nobody was going to call me a liar!

I couldn't bring the life jacket I had planned to wear; it would not fit under my pack. The wind was brisk, about 20 to 25 mph. I stepped out among the ice fishing shanties just as the sun peeked through the overcast skies, and headed for Canada.

9 a.m.: I was almost past Catawba, and the sun had disappeared into the clouds again. Several times I thought I heard the ice groaning, but it turned out to be nothing more than strange noises generated by my mischievous backpack: flapping straps, squeaking frame, etc. It took a while before I could listen to them without getting an empty feeling in my stomach. Fortunately, the ice seemed plenty solid; it was covered by a two-inch crust that made for easy walking. I soon discovered that I was overdressed: Even with the wind, I was already sweating. I took off my wind jacket and wind pants.

9:15 a.m.: I spotted my first crack, a twisting, one-quarter-inch-wide break loosely covered by snow. I unfastened my pack waistband and stepped over it gingerly, with a little apprehension. No ice movement. There would be many of these cracks through the trip, and soon I would be stepping directly on them without batting an eye. I decided to have an early lunch on South Bass (Put-In-Bay) Island, which lay just ahead. I was now about five miles out.

11 a.m.: In the summer, the ferry dock shelter on this island is a busy place. Now it was deserted, and I brushed drifting snow off the slat seats to have a look at my map while munching a granola lunch. It had started to snow as I approached land, and I had to climb over several ridges of angular, broken ice chunks with snow drifted between. These ridges, I would later discover, were formed when the terrific winds of the January blizzard pushed barely formed ice shelves into each other. The blizzard created one- to ten-foot pressure creases that helped to vary the scenery, but were impossible to climb over without bruising one's shins.

After a little reconnaissance, I finally found another ice fisherman, who supplied me with another sworn affidavit. Rather than head back south off of the island and around it, I decided to take advantage of the land and hike across it.

Noon: Advantage, hell. The lake surface was much better for walking than those hard roads. A half mile north of the island, I passed a cluster of ice fishing shacks which could probably have incorporated as a city. Snowmobile tracks were everywhere, and I could make out a few old cars sitting by themselves out on the ice, perhaps waiting for a watery spring burial. A jeep with four people in it pulled up alongside me, and the driver asked me if I'd seen Fred. "I don't even know Fred," I said, and off he drove.

1:15 p.m.: I planned to stop over on Rattlesnake Island, but on finding it surrounded by those accursed ice ridges, thought twice and headed west around the tiny island. A flock of gulls periodically swooped by to check my progress, bobbing above me and taunting me with their shrill cries. I guessed them to be frustrated vultures who'd missed their calling.

3 p.m.: "Only the Good Die Young." For some reason, I couldn't get that crazy Billy Joel song out of my head. This was the farthest I'd been from land. I could barely see East Sister Island (Canada) ahead, but knew I wouldn't make it there by nightfall. The strong northwest wind was slowing my pace. The immensity of the lake was beginning to impress me, but the only analogy I could think of to describe how dwarfed I felt was "a piece of sausage sandwiched between two giant slices of white bread." Cold does funny things to the creative faculty.

6:30 p.m.: Darkness was imminent, and I was beat. Conditioned by years of experience in camping, I intuitively began looking around for a good place to pitch my tent, then realized foolishly that one spot is as good as the next. According to the positions that East Sister and Hwen Islands occupied on the horizon, I figured my camp to be right on the international boundary. It took me a half hour to erect my tent in the wind and, as always, crawling into my warm sleeping bag after an arduous day was a near-orgasmic experience. I fired up my small camp stove and supped splendidly on canned spaghetti with Vienna sausages, oblivious to the swirling, frigid wasteland that lay just outside my comfortable quarters.

7:30 p.m.: I thought I would give my walkie-talkie a try. Its normal range is only a few miles at best, but wide open places are supposed to improve reception and transmission greatly. "Breaker 19 for a northbound on this here Lake Erie. Anybody copy?" Fuzzy static. "I'm out here on the lake. Can anybody pick up my signal?" Still nothing. "Would it make any difference if I had a broken leg, internal bleeding and frostbite?" More static. So much for my precious radio link.

8:30 p.m.: I stepped outside the tent to relieve myself one final time, and met the scene that, more than any other on the trip, would become firmly imprinted on my memory. The wind had died down to a dead calm, and my thermometer read 20 degrees. The stars were out in full force, and I could see shimmering lights onthree shores. Except for the drone of an occasional invisible plane, the silence was complete and overwhelming. It was a peaceful, striking image, and as I beheld the rare beauty of a frozen lake in the dead of night, I felt possessed by a satisfying and impregnable serenity. For that feeling alone, the trip was worthwhile.

Back into my cozy sleeping bag I crawled, taking my water bottle with me so it wouldn't freeze overnight. I fell asleep instantly.

Sunday, February 26

8:30 a.m.: The next morning found me off to my customary late start. Somehow, the earlier I arise, the more time I manage to fritter away getting ready. I blew two hours on a leisurely oatmeal breakfast, doctoring my blisters, thawing my frozen boots out with the stove, setting up a few pictures. The temperature dropped down to nine degrees during the night, but I had slept like a rock. By the time I was ready to go, it was snowing fairly heavily, and the wind was back up. For the first time on the trip, I could not see any land. I had to rely entirely on my map and compass. Since I still had better than 15 miles to cover, I scrapped my planned stop-off on East Sister and took a compass bearing straight for the mainland.

10 a.m.: The snow stopped and the sun came out. I was amazed to find animal tracks here, so far from land. The Canadian mainland was now faintly visible as a thin line on the horizon, but it would take all day to get there. I stopped for a brief rest. I had been comfortable hiking with my jacket open and gloves off, but as soon as I stopped, the cold set in immediately.

No sooner had I resumed hiking than I spied a set of footprints stretching out in front of me. Had someone else passed this way? Idiot, I thought, they're yours! Without realizing it, and without any landmarks within miles to guide me, I had turned back the way I'd come. It was an easy mistake to make on Erie's nondescript surface, and it would not be the last time I would make it.

12:30 p.m.: I entered an area of miniature ice hills and valleys, probably an ill-formed pressure ridge. Anyway, it had more character than anything I'd seen so far, and I settled in a snowy valley for a pleasant lunch. As I sat musing about this unusual snowfield, I felt compelled to commemorate Lake Erie's remarkable mutability in free verse, as if driven by the very spirit of Walt Whitman:

Lake, O Lake

Languid chameleon to our north

Mighty basin of bejeweled liquid

Mute guardian of a thousand secrets

You're really something

Cold, as I mentioned before, has a numbing effect on the brain.

The sun was high now, as high as it was going to get. My water supply was dwindling, and I melted some snow with my stove, almost falling asleep in the process.

2 p.m.: I felt like a penguin on a giant treadmill. The Canadian shoreline just did not seem to be getting any bigger. Leaning left into the wind was putting extra strain on my right pack shoulder strap. My right arm was limp and aching. My blisters hurt. My nose was running. Other than that, I felt great.

2:45 p.m.: A lone gull bobbed over me, squawking madly, as if to ask, "What the hell are you doing out here?" I could ask him the same thing.

4 p.m.: My first snowmobile track since leaving the Bass islands! Fatigue was beginning to set in, but if I wanted to reach the Canadian shore before dark, I couldn't allow myself long rests. As the sun got lower, it cast weird and graphic shadows past the protruding ice chunks and snow dunes, making the place look like a desert at sundown.

5:30 p.m.: By now, I was so close I could taste it. I could see that the shoreline was a solid 15-foot cliff, but there was no sign of a red carpet anywhere. As if a final test, the ice ridges here were the worst yet, and in my drained state, I was falling all over them. One step would be on solid ice; the next plunged hip-deep in drifted snow. I cursed them aloud, pausing only to pop cherry drops in my mouth for a final burst of energy.

Land at last! A family in a house on the cliff had been watching me stagger in for the last two hours, describing my course as anything but straight. Their teenage son and their dog came down a rickety set of wooden stairs to meet me in the twilight, and Fido ran out toward me on the ice, keeping his distance and barking warily. They invited me into their house, where I got another sworn statement and a glass of water, and answered a host of questions. My face was burning, which I rationalized as the sudden stopping of wind against my cheeks, until I beheld myself in the mirror. I was sunburned!

Physically, I was exhausted, but inside, my soul soared. I made it! I celebrated by downing a large and rather good Canadian pizza, and then set about returning home — this time, via thumb. I hitchhiked to Windsor and spent the night in a downtown high-rise motel, doubtless looking strange to the other patrons, wim must have taken me for Nanook of the North.

The next morning, I checked through Canadian customs uneventfully and then took a bus through the tunnel under the Detroit River to repeat the procedure with U.S. officials. They kept eyeing my ice ax — "That's some weapon you've got there," one of them ominously observed. After several hours I was back at my car at Catawba and by early evening, I was sitting in my apartment, my feet soaking comfortably.

A final word of caution is in order for all who might mistake my account of crossing the lake as a "how-to" article. Every winter, several people die on Lake Erie. Some fall through the ice; others succumb to exposure. If I had not spent many of my 27 years pounding back country trails and learning all that I could about outdoor survival, I could easily have been one of them. Do not even consider undertaking a trip like this if you do not have top-notch equipment and much experience in cold-weather camping. Of course, first find out if the ice is solid all the way. Keep an eagle eye on the weather reports. Bring extra clothing and food, and leave word with someone exactly where you're going and when you'll be back.

That said, I disavow any responsibility for anyone who ignores my admonition and sets out for Ontario with a Boy Scout sleeping bag and a can of Sterno. In fact, I heartily recommend the trip to all who are qualified for it, if only to discover for themselves that the world doesn't end at the East 9th Street pier and that you do not have to travel to the Sahara to sample the hidden riches of nature's vast wastelands.

There are some people who are trying to make it illegal to walk across the lake. But they'll never do it, not as long as we have a Constitution. Hiking is a bona fide recreational use of the lake, certainly no less legitimate than fishing or water skiing.

Colin Fletcher makes the point much better than I in his book, The Complete Walker. To those who still wonder why anyone would want to walk across Lake Erie, this excerpt comes as close to an answer as you're going to get:

If you judge safety to be the paramount consideration in life, you should avoid at all costs such foolhardy activities as driving, falling in love, or inhaling air that is almost certainly riddled with deadly germs. Never cross an intersection against a red light, even when you can see that all roads are clear for miles. And never, of course, explore the guts of an idea that seems as if it might threaten one of your more cherished beliefs. In your wisdom, you will probably live to a ripe old age.

But you may discover, just before you die, that you have been dead for a long, long time.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5