Life Without Father

by Renee Krause | Jan. 29, 2020 | 5:00 PM

Editor's Note: This story, originally published in November 1992, is being republished as part of Cleveland Magazine's "Historic Read of the Week" series. In 2019, Netflix released a new docu-series titled "The Devil Next Door" exploring the John Demjanjuk case, and in 2020, new evidence emerged potentially suggesting Demjanjuk was a guard at Holocast camp Sobibor in Berlin.

The Demjanjuk family was gathered in the sun room of their Seven Hills home that summer Sunday 11 years ago. Only 16-year-old John Jr. was outside, sanding down his 1971 Ford Torino, when a tall, black-hared man walked up the drive. Ed Nishnic was on his way to pick up John Jr.’s sister, Irene, for their first date.

Walking toward the tan-brick Seven Hills house an hour and a half late, the 25-year-old worried about the impression he would make on the family.

He had only learned the sweet, shy secretary’s last name when he glanced at a piece of paper one day and saw the word after her first name: DEMJANJUK. As in Nazi war criminal. Ivan the Terrible, one of the most heinous criminals of the 20th century, who slashed off women's breasts with a 6-foot sword as they headed for death in Treblinka’s gas chamber.

The descriptions all came back as Nishnic, a gregarious, lanky graduate of Rhodes HIgh School, walked into the Demjanjuk house carrying a box of oatmeal cookies. Before that time, he hadn’t considered the allegations against Irene’s Father. He wanted to date her, not her dad.

But as he neared the sun porch, Nishnic found himself not only thinking of making a good impression. He also recalled the media reports.

“I looked him in the eye. He gave me a good handshake,” Nishnic remembers. “I thought he was a genuine guy. I was really amazed by how nice they all were.”

For Nishnic, that Sunday afternoon of picnicking at the beach would change his life. Two years later he would marry Irene. Three years after that he would put his career on hold, dedicating every waking moment to his father-in-law’s defense. And muscle-bound John Jr. would become his partner, their combined strength of will dedicated to undoing the wrong the claim was committed by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Israeli Supreme Court. For six years and counting, the men have toiled in the Demjanjuk family basement, giving up social life and a semblance of anything most would consider a normal life.

The question of John Demjanjuk’s guilt, of whether the now 72-year-old man poked 850,000 Jews as they headed for their deaths in Treblinka’s gas chambers or stood guard at another Holocaust camp called Sobibor, is about to be determined by the same Iraeli high court that convicted and sentenced him to death in April 1988. At the same time, a federal appellate court in Nashville is preparing to hear testimony from members and former members of the Justice Department Office of Special Investigations. Men from the OSI masterminded the case that stripped John Demjanjuk of his citizenship and then sent him to Israel to be tried in what was only the second Israeli trial of “crimes against the Jewish people.” In the first case, Adolf Eichmann was convicted in 1961 and hanged a year later after he admitted he had helped create Hitler’s death machine that killed 6 million Jews.

But the question of why and by what power Demjanjuk’s children and their spouses forge ahead, focused only on the day when they believe the Demjanjuk family will be reunited can be answered: HIs children — and their spouses — are guilty of nothing more than loving their father.

While John Demjanjuk sits in a 12-by-12-foot cell in Ayalon Prison outside Tel Aviv, his offspring, too, live in a prison. The have passports and have traveled the world, but it has only been in search of information they hope will free John Demjanjuk. When the shop at the West Side Market, they cannot maneuver through the throngs without someone yelling out their names and asking about the case. Though they can go out and socialize, they don’t. They haven’t the time. And in the case of Ed Nishnic, father of 6 ½ year-old Eddie Jr. and 3-year-old Olivia, he is a dad who has missed milestone moments in his children’s lives, including their first words and first footsteps, because he was off in another country searching out death camp witnesses and the man the world may now believe is the real Ivan the Terrible.

“You want to know what drives me? It’s that my wife didn’t deserve this. Mr. Demjanjuk didn’t deserve this,” Nishnic said recently after a meeting at the Federal Public Defender’s office in Tower City. “It’s not just a crime against one man. It’s a crime against an American family.”

Over the years, Nishnic, 37, and John Jr., 27, have become experts on myriad subjects. They know more about the Holocaust than most Jews. They can talk in sound bites for television and radio and take any reporter from the beginning of their story to the end, always punctuating their tales with their belief that John Demjanjuk is an innocent man. They’ve appeared on 60 minutes, Good Morning America, Good Morning Australia, Dateline NBC and have been interviewed for Vanity Fair, Newsweek, The New York Times and just about every newspaper across America and Europe. They understand legal documents and can point out what they would call legal shenanigans. And they’ve become beggars, asking for money to cover the estimated $2 million they have spent on legal fees and travel costs to defend John Demjanjuk.

They did not have access to the unknown millions spent by the U.S. and Israeli governments trying to prove the former auto worker was Ivan the Terrible. All this has come to two regular guys as Nishnic calls himself and John Jr. Nishnic says he completed two college courses. John Jr. finished two years of classes toward what he still hopes will be a bachelor’s degree in finance. Neither ever envisioned a life of press conferences and fighting bureaucrats.

John Jr. was 11 years old, a sixth grader at Seven HIlls Elementary School, in 1976 when all the allegations began and strangers appeared at his house to talk to his father about a war that happened years and years earlier in some faraway land. Now a tall, quiet yet confident man, it’s hard for him to recall the emotional trauma caused during his formative years.

He prefers to concentrate on the good times he shared with his big bear of a father. Like millions of sons worldwide, John Jr. believed in his father. Whatever promise his father made, he kept. He worked hard. And when home, he was sensitive to his son’s needs and wants. John remembers when he was 13, he and John Sr. took a day trip to Cedar Point — just father and son. While John Jr. rode the roller coasters, John Sr. watched from the sidewalk below. “He just watched me on the rides. He did go on the Cadillac cars with me. I remember that,” John Jr. recalls, the corners of his mouth moving into a smile.

The man John Jr. knew and for whom he now dedicates his life enjoyed working with his hands, planting and tending to a vegetable garden, growing grapes and making wine.

He also liked working in the house. John Demjanjuk nailed the dark wood paneling in the family basement, glued down the linoleum and even built a second kitchen for his wife, Vera, to cook in during the hot summer months.

Now John Jr. is a father. His first child was due in late October, just when this magazine will hit the newstands. He dated Linda, an insurance executive who supports John Jr., for five years. When they became engaged, he brought Linda to Israel to meet his father in prison. “I always thought and I”m sure he always thought he’d be at the wedding. I’m his only son, and you think He’d be there to be a part of it.”

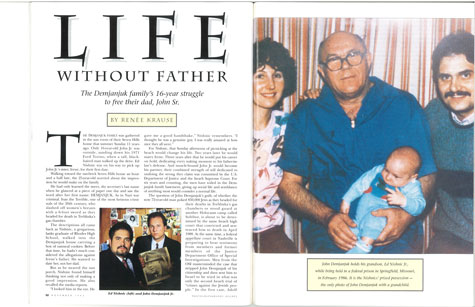

The toll on the Demjanjuk progeny exists beyond the second generation. For JOhn Demjanjuks’ grandchildren, the man they call “Dido,” Ukranian for grandfather, is but a picture in a scrapbook, a face on the television screen, a voice on the phone every other Sunday.

The day Eddie was born was one of the toughest on both Ed and Irene Nishnic. John Demjanjuk was in solitary confinement in Springfield, Missouri, awaiting extradition to Israel. Ed kept trying to reassure his wife that the mistake would be learned and her daddy would not be taken away from her. But on December 10th, 1985, Irene gave birth. “They let him out of this 12-by-11-foot room and let him call the hospital. I can remember she was handed the phone. It was one of the hardest things for me to watch. She just cried,” Nishnic says.

Six years later, Eddie’s link to Dido comes from stories he has heard about his grandfather's power-tool prowess. “Come home. You can fix my tractor,” is Eddie's refrain when taking his turn during Sunday afternoon conversations. On those days, the whole family lines up near the kitchen wall phone to talk during the collect calls from prison. Vera Demjanjuk always talks first. Then John jr., catching up his father on the case’s progress in Ukrainian. From there, it’s a grandchild or a daughter. Ed Nishnic usually closes the conversation. John R. and Vera Demjanjuk’s two daughters, Lydia, 43, and Irene, 33, have chose not to let the men in their family lead the fight to free their father. Like their mother, neither woman will talk to the media. Instead , the tend to their families and help by lending financial and emotional support. Ed Nishnic often talks of how the original allegations and the ongoing trial and appeal process have “destroyed” his wife.

Eddie watches all the goings on. Sometimes his parents don’t realize the effects until their son recounts a story from school. Like most children, Eddie and his friends talk about how their fathers earn a living, Ed Nishnic says. One child says his dad is a lawyer, another works at the Ford plant. “Eddie says, ‘My father works in Babunya’s [grandmother’s] basement.’”

Life for Nishnic is Babunya’s basement. Since 1986, Nishnic an d John Jr. have created central headquarters out of the shell that John Demjanjuk left behind. The last time John demjanjuk saw the basement was the day after Easter in 1985 when he was hauled away for a temporary stay in Springfield, Missouri, before heading to Israel.

Nishinc, an ever boisterous man with a quick smile and a quicker retort, greets a guest with, “Welcome to the bunker!” In the far corner of the long and narrow, dark, cave-like room, Ed Nishnic leans back in a chair, size-11 feet propped up on the desk, left hand gripping a phone receiver. It is his most natural position. For years he has worked the phones, locating witnesses in his mission to prove that his father-in-law, his wife’s father and his children's grandfather was not one of the most proficient mass murders of the century.

To his left is a fax machine, spitting out missives from Israel, Washington, D.C. and downtown Cleveland. A few feet down that wall is a copying machine. Six feet over his right shoulder is a dinosaur of a computer, a big heavy machine that holds in its memory the list of thousands of people who have donated to the John Demjanjuk Defense Fund. In between the equipment are about 18 feet of files. Hidden away are dozens of boxes filled with more information about the Holocaust, the Russian Army, Treblinka and the man now suspected of being the real Ivan the Terrible, Ian Marchenko.

These two men of Eastern European descent, John Jr. and Ed, who is third-generation Czech and Carpatho-Rus, learned the same as most junior- and high-school students about World War II and the Holocaust. Basically, they got the minimalist explanations.

Now the men are experts. They can recite the death amps by name. How many were murdered. Each has crossed the Eropean continent in search of witnesses who can tell them about Ivan the Terrible, about convicted Nazi conspirator Fedor Federenko, who was stripped of his U.S. citizenship and shot to death by fireing squad upon his return to then Soviet Union. They’ve been to places such as Dnepropetrovsk and Babaykovka in Ukraine. They’ve held press conferences in Kiev, trying to prompt the KGB to release what now may be the evidence that overturns John Demjanjk’s convicted as Ivan the Terrible. In all, more than 80 people testified in the former Soviet Union that the man at the Treblinka gas chamber was Ivan Marchenko.

“I’ll sit down with any Ph.D. in history and discuss the ins and outs of the Holocaust. I’d sit down with any Jewish scholar. I might be able to teach him a few things,” Nishnic says confidently.

Their passports are testimonials of their dedication and determination. Red, purple and green shapes mark page after page of the blue books. Each has been in and out of Israel so many times their everyday language is spiced with Hebrew and Yiddish words. They turn on an Israeli accent at will a la Rich Litt., when they need to bring a little levity to any situation. Without thinking, they both use the Canadian colloquialism “ey” from the year or more they spent traveling from Montreal to Vancouver in search of financial and emotional support from the large Ukrainian-Canadian population.

When Nishnic dreamed as a child or even as an adult, he envisioned tips more like “Hawaii and Acapulco.” Instead he has been to one of Hitler’s most efficient death camps — Treblinka — six times. The place is a magnet to him.

“The camp is a memorial to what went on. I go to pray for the souls that were lost. For so many years my life has been focused on Treblinka, what went on there. I walked on the very grounds where people were slaughtered standing on the two pits where bodies were tossed. It’s sort of a twisted feeling,” Nishnic says as his speech slows and this usually gregarious man grows quiet and withdraws into himself.

John Jr. tries to help. “It’s the scene of the crime.”

Regrouped, Nishnic continues; “it has involuntarily taken over our lives. It’s like going to a cemetery. About six kilometers off the main road. There are beautiful forests surrounding it. An open blue sky, constraint what we know happened in there .. You see the rail cars that brought the Jews there. You have the cabbie pull over and climb up inside them and try to feel how these people felt, locked inside with no water and holes in the ceiling.”

Nishnic begins to quiver and shake. John Jr. helps again: “You want to try to understand how it happened. You keep getting hit between the yes that you cannot understand how it happened. You cannot understand how human beings can do inhumane things to other human beings.”

Nishnic feels stronger again and continues: “So you go and try to explore it. You become obsessed. It takes your life over. You follow in the steps of where Ivan used to go. You make a left out of the campe and head toward the town where he’d go to drink.”

Through the years of research, the two men have read thousands of pages of testimony form HOlocaust survivors of the horros they endured. They recall the descriptions of fetuses being cut from the bellies of pregnant women, of babies being tossed into raging fires. “Who can comprehend that?” John asks.

It is a genuine empathy they feel for the survivors and particularly for those who testified against John Demjanjuk. During the Israeli tRials, 12 survivors of Treblinka testified on a stage-turned-courtroom that John Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible. But John R. and Nishnic harbor no animosity toward them. The tow young men say the survivors did nothing more than repeat what they were told. Both U.S. Justice Department spokespeople and Israeli officials all but convicted him before he ever went to trial, they say. What were the survivors who testified to think?

“They’ll always believe they did the right thing because they were manipulated,” Ed Nishnic says. “What may happen to the survivors is they’ll feel betrayed by the very people who set them up. This in no way should diminish what happened. The living martyers, the survivors of the Holocaust, were put on a stage before the entire world at the behest of Isrwael, working hand in hand with the United States Deptartment of Justice.

Nishnic married into the family. He believed in his wife and her love for her father. But it wasn’t until he and the man he often refers to as “Mr. Demjanjuk” or “Mr. D” were alone one day in 1984 or 1985 that Nishnic says he finally got the guts to ask his father-in-law: why you? Why is this happening to you?

What he remembers most from that conversation is John Demjanjuk’s saying that if the allegations were true “the easiest thing to do would be to take a bottle of sleeping pills, will everyting over to the family, save the family shame and go to sleep forever.” John Demjanjuk knew that the end result for a guilty man was death. “I am innocent. I will fight this,” Nishnic quotes his father-in-law.

As it turns out, it is the Demjanjuk family that has fought the older man’s battle while John Demjanjuk sits in solitary confinement. Vera Demjanjuk has remortgaged her small Seven Hills home and sold every non-necessity, down to the lawn mower, to come up with money for her husband’s defense. And still the family is $160,000 in debt. Nishnic, who continues to rent a home because he hasn’t earned an income in more than six years, had to take a $3,000 loan on his 1987 car to pay off creditors. Their financial woes were eased recently when the U.S. government assigned a federal public defender to work on the case before the 6ht District Court of Appeals on whether government officials mishandled the case and withheld crucial evidence.

Nishnic sometimes describes their fight as the proverbial David versus Goliath story. Other times he teases that he and John Jr. are the caped avengers from Gotham, Batman and Robin, fighting for the rights of every man and woman.

The lowest point over the years was not the conviction, not the sentence of death by hanging, Nishnic says. Instead, it was the suspicious death of one of their Israeli attorneys five days before the start of John Demjanjuk’s appeal.

Dov Eitan, a former Israeli judge, left his home at 8 one morning, asking his wife to meet him before lunch to help pick out a new suit for the upcoming trial of his career. By 8:30 a.m. he was dead. His body lay splattered on the ground after he supposedly jumped from a 15th -story window.

The death was ruled a suicide. Though Eitan’s daughter said that her father was depressed over losing his judgeship, Nishnic and John Jr. say he was optimistic about the case and talked positively about the future.

Then, at Eitan’s funeral, someone tossed acid into the face of their other Israeli attorney Yoram Sheftel. The acid burned one of Sheftel’s eyes. “So then we were down to a one-eyed attorney,” Nishic jokes in the humor of a pained man.

Other challenges have included suspicions throughout their crusade of being wiretapped by the U.S. government. Now armed with what they say is clear proof that certain individuals within the Justice Department knowingly withheld information that would have cleared John Demjanjuk’s name before it was ever sullied, they have no doubt that Big Brother has been listening in for years.

And Ed Nishnic became the subject of an 18-month FBI investigation that suggested he stole government property. In fact, the property was Justice Department garbage that was donated to the Demjanjuk cause and contained the now valued information that they say will bring John Demjanjuk home.

Mary Lax is a Holocaust survivor who tried to raise money for John Demjanjuk’s defense. A resident of Pepper Pike, he followed the local trials and called Demjanjuk’s oldest child, Lydia, to offer help. Even if JOhn Demjanjuk were Ivan the Terrible, Lax wanted him to be spared the death penalty and be foreced instead to talk about the atrocities of the Holocaust.

“I’ve always thought there couldn’t be justice in this case, but at least there could be truth,” Lax says.

Over the years, Lax became close to Ed and Irene Nishnic. They met Lax for lunch at his Akron restaurant and talked about the case. Lax, for one, credits Nishnic with what appears to be a turn of events for Demjanjuk. “Everyone should have a son-in-law like Ed. He saved his father-in-law’s life because he loves his wife.”

It is a life with his wife, Irene, and their two children that Nishnic longs for. But he wont have that until he brings his wife’s father home. “We’ll just be happy to get him home and try to rebuild our lives,” Nishnic says.

Speaking at the City Club on September 16th, Nishnic said the family doesn’t contemplate the possibility that his father-in-law will not come home. That has been the goal from the start. Last June, Nisnic was so optimistic that the end of the ordeal was imminent that he ordered business cards for himself. He even reserved space in a new office building for the head-hunting business he hoped to start.

By August, the building owner had rented the space to someone else. And Ed doesn’t use his business cards. The Demjanjuk case continues.

And John Jr. still dreams of returning to Cleveland State University, finishing his finance degree and then going into business for himself. He doesn’t know what type fo business. Unlike his brother-in-law, he’s tired of being a headhunter.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5