The city was hungry.

It was 5 p.m. on Thursday and we were all starting to realize that it might be a while before the power came back on. In the suburbs, folks with yards grilled steaks and salmon, while we city-dwellers were forced down dark stairwells to scavenge for food on the lean streets of a sweltering city.

In the Gateway District, Panini's was game-day packed. The beer was flowing. The suit jackets were off. The after-work crowd grew hungry. A few tables over, we spotted a guy with a sandwich. By the time we made our way inside to order one, the source had dried up. Scavengers are nomads. We moved on.

In the Warehouse District, most restaurants closed early. But Johnny's Downtown, backed up by two grills they use for Browns games, was open with a menu of half chicken, strip steaks, grouper and burgers. The line was 20 deep down the street.

"People had nowhere to go," remembers Johnny's general manager, Andy Lowrey. "Traffic was jam-packed. They sat on our patio and weathered the storm." Those served that night included 20 players from the Green Bay Packers and the cast of "The Lion King." Some folks were so grateful they wrote thank-you notes.

Farther down on West Sixth Street, hip-hop music blasted from a parked car while half-price beer was served to a crowd that spilled onto the sidewalks. We ran into our friend Steve, who was on a date that couldn't be downed so easily. "Why sit home alone in the dark?" he reasoned.

As the crowds thinned out, we walked back home to the Theater District. The police were out, as were the TV crews, broadcasting to dark TVs. The festive atmosphere had vanished, replaced by small clumps of people bonded by a reluctance to go home to warm, stale apartments.

Meanwhile, Steve and his date had returned to the rooftop of his Flats home for wine, cheese, stargazing and the cool breeze that swayed the hammock in which they lay. Around 2 a.m., they watched the lights come on "like lazy fireflies in a slow sweep of downtown."

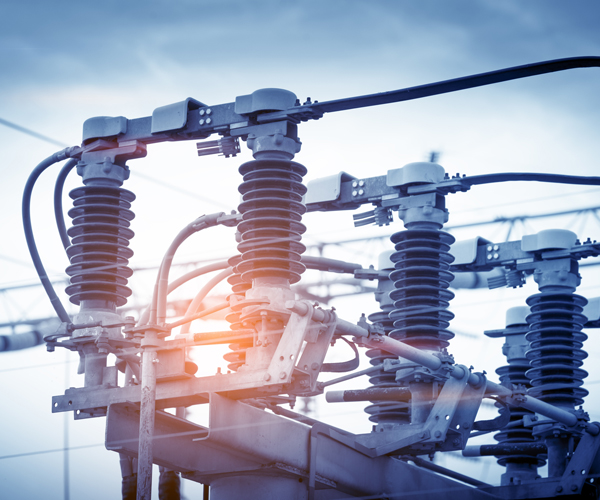

If the Boy Scouts of America handed out merit badges to those most prepared for the blackout, the city of Oberlin would undoubtedly snag one. Unlike most local communities, which rely solely on the nation's power grid for electricity, Oberlin maintains its municipal power plant&to provide backup power in a pinch.

Oberlin Municipal Light and Power director Steve Dupee says his staff fires up the plant on hot summer days when the city experiences low voltage, meaning electric current moves through utility lines slower than usual.

"Everybody's got their air conditioning on and industrial customers are running at full steam," he explains.

But on the sweltering afternoon of Aug. 14, voltage dropped much lower than usual even for a mid-August afternoon, according to Dupee.

"Shortly after 4 o'clock, it just dropped off the face of the earth," he says.

When Oberlin lost power, Dupee's department wasted no time turning to the city's municipal plant to fix the problem. Electricity was restored to many households by 5 p.m., while everyone had power by 9 p.m. And unlike so many Greater Clevelanders, Oberlin residents never went without water. The city's water and sewer plants have their own generators.

SEEING STARS

Blame Clyde Simpson. While most of us were longing for air conditioning and a hot meal, he was praying the electricity would stay off at least a few more hours.

An observatory coordinator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and an avid stargazer, Simpson was one of the few Clevelanders who thoroughly enjoyed the blackout. A few hours after the lights went off, Simpson's telescope went on.

"It was absolutely beautiful watching these stars emerge," he says. "For the first time in my life, I could see these things from Cleveland. I was just flabbergasted. On normal conditions, you can see perhaps a few hundred stars. On that evening, you could see a few thousand."

For years, Simpson has been a staunch supporter of anti-light-pollution legislation geared toward restricting the amount of lighting uselessly directed upward instead of downward. He's hoping the blackout will convince others to take up the cause.

Your mother tells you refrigerated food will keep for six hours during a blackout. Your co-worker advises you not to open the refrigerator door under any circumstances. Your family just wants a decent meal once power is restored. Do you dare eat the food warming up by the second behind that big white door or do you simply throw it all away?

Highly perishable foods such as milk, beef, poultry and fish will stay safe for about four hours if the refrigerator door is never opened, according to the Ohio Department of Health. Foods in a freezer at least half-full will stay frozen about one day if the door remains closed. Foods such as butter, fresh fruits and vegetables, hard and processed cheeses and fruit juices can be kept up to three days in an unopened refrigerator.

Another route is to buy a refrigerator thermometer and throw out all meat, milk, yogurt and eggs once the mercury rises past 40 degrees.

If the blackout made you edgy about your vast dependence on electricity, an old-fashioned general store in Kidron, Ohio, can help wean you off the juice.

Originally devised to serve the surrounding Amish country, Lehman's now caters to a diverse population seeking reliable alternatives to modern technology.

"People can do this elegantly and graciously and they can easily live off the power grid," says marketing director Glenda Lehman. "Some people are just minimizing their dependence on electricity."

Since 9/11, Lehman says she has seen more people incorporating electricity-free products into their lives. The store's products range from hand-cranked flashlights ($50) to butane-powered clothes irons ($167) to water filters ($7 to $389).

"People are sick of getting caught off guard," she observes. "It's smart to have a backup plan. Just buying a flashlight with batteries and a jug of water is a temporary measure."

For those wishing for a complete lifestyle makeover, Lehman's even has a handbook in stock: "How to Live Without Electricity and Like It."

GIVING BIRTH IN A BLACKOUT

Jasmine Carman, 18, gave birth to her first child, Kayla, at St. John West Shore Hospital in Westlake on Aug. 15.

"I was 11 days past my due date and about to be hooked up to the IV to have labor induced when the lights went out. Nobody knew what was going on. The only thing I had in my room that worked were two overhead lights. I had to take a flashlight with me to go the bathroom.

"Once we knew it was a blackout, they decided to send me home. That's when the nurse noticed I had started to have contractions -- on my own. It was about five in the afternoon. I was hoping the power would come back on before I had the baby.

"From there, things went slowly. There was no air in the room. It was extremely hot. Hospital windows only open 2 inches, so you don't get a breeze in there or anything. It was horrible. They were going to give me a Popsicle, but the freezer wasn't working and they had all melted. The only thing I got was a glass of ginger ale -- room temperature.

"Besides that, it was boring. There was no television. When you're in labor and you're just lying there, you need something to do. There were special red outlets in the room that still worked and I asked if I could plug the TV in for a little while. They said no. My mom went out and got magazines from the waiting room for me: People and Country Living, which is not really my type of magazine.

"By 6:15 a.m., I decided I wanted an epidural. The anesthesiologist hooked up the line, but I had waited too long and he couldn't do it. The actual birth was so quick. It was painful, but it was over with so fast. It was hot. That was the worst thing.

"I had Kayla at 6:48 in the morning. The power came on 20 minutes later." — As told to Cleveland Magazine

TRAPPED IN AN ELEVATOR

Geraldine Bryant, 44, is an employee of Lakeside Building Maintenance. She was stuck in a Superior Building elevator for more than five hours.

"The lights went out and my car jolted to a stop between the sixth and seventh floors. The first thought running through my head was: terrorists. I didn't panic, but I wanted out of that car as soon as possible. I pressed the emergency button. I hollered that I was trapped and banged on the side of the elevator. Bam! Bam! Bam! No one answered. I sat in the dark and wondered if I would be stuck there all night.

"About 30 or 40 minutes later, I heard maintenance workers yelling whether anybody was trapped. They heard me. An hour or so later, they got into the blind elevator shaft I was in and pried open the doors of the car 5 inches or so with a crowbar. That's all the farther they would go. Someone handed me a little flashlight. A co-worker handed me a cigarette. I sat in the corner and waited.

"Later, a woman from the Associated Press office brought me a small bottle of water. Hours passed. There was nothing to do but wait and think — mostly about having to use the restroom.

"A little after 9 p.m., they were able to bring the elevator down to the first floor and get me out. Most of my co-workers waited to go home until I was safe. I even went to work the next day. My nerves still get me using the elevators. I just move faster now." — As told to Cleveland Magazine