As I sit wedged in the passenger's seat of Brandon Chrostowski's cluttered black Audi sedan, a French baguette stashed between our seats, the world-traveled chef and restaurateur asks me about the South. You know, what it's like, because he's never been there.

So I tell him homeowners paint their porch ceilings blue. I tell him it's a civic responsibility to drink before noon. I tell him I miss Conecuh sausages.

"What the f--- are Conecuh sausages?" Chrostowski interrupts.

"I don't know," I stutter, startled by the blunt force of his question. "They're just these awesome sausages made in Alabama. I don't think you can get them here. And if not, I'm considering airlifting several pounds to my apartment so that I can make my red beans and rice."

His mild curiosity becomes a mission. As he toils to open Edwins Leadership & Restaurant Institute, the monumental minutiae of the day — picking paint swatches and plate patterns, composing curriculum and menus, sifting through supplies and applications — wait. Within an hour, Chrostowski has found the sausages at the Shaker Square Dave's Market, purchased enough of the pork for 30 people and requested my red beans and rice recipe.

He texts: "Going to see how good it is and if so, squeeze it on the menu somewhere."

He also wants me to teach 16 inmates at Grafton Correctional Institution how to make the classic Southern dish.

****

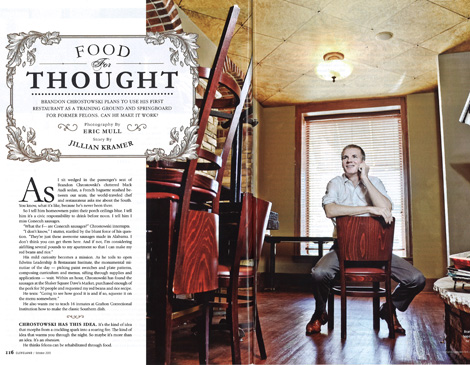

Chrostowski has this idea. It's the kind of idea that morphs from a crackling spark into a roaring fire. The kind of idea that warms you through the night. So maybe it's more than an idea. It's an obsession.

He thinks felons can be rehabilitated through food.

"People think I am f---ing nuts," Chrostowski says. "But people who aren't as crazy don't make as much of a difference in life."

Last September, the lanky, gray-haired 33-year-old former general manager of L'Albatros Brasserie & Bar in University Circle revealed his plan for Edwins, a nonprofit started in 2007 to help formerly incarcerated men and women cultivate culinary expertise.

He launched classes at Grafton Correctional Institution and Northeast Pre-Release Center this February as a prelude to his greater plot: To open the nonprofit storefront restaurant staffed by his first wave of students.

To say that Chrostowski's plan is ambitious is like calling McDonald's fast-food fries French cuisine. It's a tad crazy.

In July, he purchased the corner restaurant once known as Grotto Wine Bar in Shaker Square with funding from private donors and foundations. He's turning the restaurant upside down, tearing out sections of a U-shaped bar and adding a lounge area, until the intimate space with seating for 85 will no longer resemble a wine bar but a fine French bistro.

In late September, 60 students — all ex-cons — are expected to begin training in the restaurant's cramped basement, learning skills such as culinary math, wine pairings, the history of food, and safe serving and sanitation practices. Their curriculum, however, is still a rough draft just a few weeks before they arrive.

Chrostowski plans to open the restaurant to the public by the first of November — long before the six-month culinary training course is complete.

Ask him if it can be done and he balks. He looks at you like you're stupid, like the question is outrageous. In his mind, no goal is unattainable, even if the steps along the way appear as confusing to an outsider as an M.C. Escher lithograph.

Cocky? Sure. But to Chrostowski, there's a wee bit at stake.

"Shit," he says. "If you have been passed over, if you have never been given an opportunity to make history or be a part of something that is bigger than yourself, when you get a taste of it, when this thing flourishes — you can do it in a month."

He points to Anthony Smith, the first man to walk out of Grafton prison after participating in Chrostowski's prison-based class. Within 12 days of his release, Chrostowski secured a job for Smith at the Katz Club Diner, working as a saute cook. They hang out a couple nights a week, Chrostowski says.

Smith even has keys to Edwins.

"What did he do?" I ask.

"I don't know," Chrostowski scoffs. "What the f--- do I care what he did?"

****

Smith used to sell cocaine.

"It ain't been pretty," he admits.

He was born to an African-American mother and absentee Chinese father, whose affair began behind the kitchen doors of a Chinese joint and ended while Smith was still a child.

"I used to like to go in and watch the cooks," Smith says. "I wanted to be like my father, even though I never really knew my father."

He landed at a TGI Fridays, pulling in $25,000 a year as a line cook. "It wasn't enough money for me," Smith says. Then he repeats a well-worn tale: "So I turned to a life of crime."

He was arrested in 2010, convicted of receiving stolen property and forgery, and sentenced to three years at Grafton. Near the end of his sentence, Smith got wind that an outsider would host a culinary class each Sunday.

"I was overhearing guys say they were taking the class just to take it — just because hopefully they could get to eat," Smith says. "They weren't really into the class like that. And there are some guys in there doing life in prison — they're never coming home."

As those inmates noshed on finer-than-cafeteria cuisine and neglected their notes, Smith studied culinary math, brushing up on what shaving an ounce of fat off a New York strip steak can cost a restaurant.

"I knew I was coming home," Smith says. "I ended up being the first one to come home out of the class."

After checking into an East Side halfway house, Smith dropped Chrostowski a line. "He wanted me to be his success story," Smith says. "I developed a relationship with Brandon in the class. Because, you see, Brandon is very observational. He was ready for me when I came home."

****

Years ago — when Chrostowski was something like 15 or 16, because even he isn't sure at this point — somewhere just outside of Detroit, he ran afoul of the law.

There were drugs. There were other teens. There were police. And there was Chrostowski, until he ran. "Fleeing and eluding," he says. "And that was all they could get to stick."

He's since had his record expunged — even speeding tickets, he admits — so Cleveland Magazine was unable to independently verify Chrostowski's account.

"Why expunge them?" he asks. "There are a lot of reasons." Liquor licenses are easily tangled in the red tape of criminal records. "If you get it expunged," he concludes, "it's cleaner."

He'll close the door on any conversation leading to his childhood or arrest. Push for too many details and he responds, "I don't know."

Whatever he did, Chrostowski's crimes went largely unpunished. "We got a good attorney," his mother, Debra Ward, explains. "He was faithful and diligent and got himself squared away."

There is a seconds-long silence when the 60-year-old single mother is asked how her son got mixed up with drugs. "I didn't know anything about the drugs," she replies. "He lets me believe what I want to believe."

Chrostowski was raised by his mother in Sterling Heights, a 36-square-mile suburb of Detroit, the middle child of three boys.

As if born with a sense of how smell relates to taste, the then-sandy-haired Chrostowski sniffed his food before touching it to his tongue from the time he was old enough to hold his own spoon.

"He'd hum all the way through a meal," Ward recalls. "If he didn't like what I was cooking, he was silent."

He was a natural athlete, a free spirit, a go-getter with Fred Flintstone-like feet that spun wildly toward a goal.

He refused to lose. He got what he wanted, his mother says, by doing whatever it took. "He'd change the marks on his report card," she says. "I would hold them against a window and see that a C had been changed into a B. That, or he'd hide the report card in the couch."

His father left the family when Chrostowski was 10. Then, Ward says, when she refused to supply groceries for the children on his weekend visits, he simply stopped picking them up.

Chrostowski was also angry. "I'm not sure where his anger comes from," his mother says. "Maybe it was because we got divorced. He's got a very short fuse. He's not afraid to explode."

****

"There is a lot of anger inside me," Chrostowski admits. "It's masked very well, but anger is also energy, just like love is energy, or passion is energy. And you can take this energy and you can direct it in a certain way that can make things jive."

Escaping prison time served as Chrostowski's figurative and literal come-to-Jesus moment. "I believe I am on borrowed time," he says. "I'm not in prison. I feel like I should be in prison, I feel like I shouldn't be here."

He found a restaurant in Detroit with a chef willing to take him under his wing, a man who encouraged his food-centric curiosity — a man who answered Catholic-raised Chrostowski's questions about God. "I could crack open a Bible and point to a passage, and he would talk to me about it," Chrostowski says. "The more I would pursue that [religious] path, the more things would open up."

By 2000, 20-year-old Chrostowski had scored an apprenticeship at Michelin-starred restaurant Charlie Trotter's in Chicago. Within five years, he earned a bachelor's degree from the Culinary Institute of America; worked as a private chef; and studied under chef Alain Senderens in Paris.

"He just went on a whim," Ward says of her son's trip to France. "He didn't have very much money, he didn't know the language. He just took off. He's right on the line between stupid and brave."

He worked the amuse-bouche and patisserie stations at the now-shuttered Lucas Carton for nearly six months. But he hated Paris: "It smells like urine," he says.

Chrostowski returned to the states to serve as the saucier at New York City's Picholine and manager of Chanterelle before venturing to Cleveland in 2008, working his way up to general manager at Zack Bruell's L'Albatros.

"His energy is really unmatched as far as people I have worked with in the past," says Sean McNeil, general manager of Bruell's Cowell & Hubbard and former assistant manager under Chrostowski at L'Albatros.

During his almost five years at L'Albatros, Chrostowski established a reputation among Clevelanders as a cheese and wine expert. His cheese board introduced even the hard-core foodies to curds they'd never tried, and he hosted cheese and wine pairing classes to educate the staff.

Charming and handsome, he's also a first-class schmoozer in tailored suit jackets, cared-for leather shoes and socks that match his shirts to irritating perfection.

But a need for perfection comes with a price.

"He's very dedicated," McNeil says. "But he was also very demanding of people."

Chrostowski admits to axing — with or without owner Bruell's permission, it's unclear — three dozen people during his first months at L'Albatros. "Perfect practice makes perfect," he says, justifying cutting individuals who weren't cutting it.

"They understand how I push and when I do, it's for a reason. It's not just to be a dick," Chrostowski says. "It's to get the most out of somebody. If I manage you, I'm losing. I'm stupid, and I'm not doing my job. But if I'm managing your potential, I'm doing what I need to do, and that is to make you a better person, on and off the court, in and out of the restaurant."

****

And that gets to the crux of the matter. Chrostowski isn't breaking new ground. He's not the first to attempt to rehabilitate inmates and ex-cons. He won't be the last.

Whether Chrostowski can succeed is an important question, because it's not an overstatement to say that what the United States does with its prison population is one of the more serious problems facing the country today.

A 2011 Pew Research Center study, titled State of Recidivism, has shown that as recently as 2008, nearly one in 100 American adults were behind bars. That's 3.1 million people — 10 times the level in 1978 and double the number of people living in the country 250 years ago. And one in 31 adults in the U.S. were incarcerated or on probation or parole in 2009.

The center's study also revealed that just shy of half of felons released from prison in both 1999 and 2004 were re-incarcerated within three years. In fact, recidivism rates across the country hovered steadily at about 40 percent from 1994 to 2007.

In Ohio, recidivism rates rose ever so slightly, from 39 percent from 1999 to 2002 to 39.6 percent from 2004 to 2007.

The Pew study concludes, "If more than four in 10 adult American offenders still return to prison within three years of their release, the system designed to deter them from continued criminal behavior clearly is falling short."

So why should Chrostowski succeed where others have failed?

"You beat them from the inside out — you just don't stop. You don't stop," he says. "You let them know that every step they are taking here in this restaurant is a step in history that they make for everyone."

It's a broad, confident answer. The kind of frustratingly simple solution that only a visionary or a lunatic would believe. But he absolutely does — that with enough sweat equity and sheer willpower, he can do it. And he makes you want to believe it too.

We're driving again, past an East Side plaza with a Rent-A-Center and a cash advance storefront that you know will take advantage of every customer who walks in begging for a $100 loan with a 30 percent interest rate.

"I hate these places, man," Chrostowski says. "They just prey on people. You wonder why these people are scared, why they think they can't do it. It's these places. I mean, go into one of these other re-entry places, and talk to some people there. You'll see — these people feel hopeless."

****

There are a dozen errors in Das Schnitzel Haus' brunch menu, but the six students in North Star's Tuesday morning GED certificate class can't find them.

"Did anyone find five?" asks the instructor, Rita Shepard. No one moves.

"More than five?" Again, nada.

"Anyone find less?" She moves to a whiteboard and writes down the price of the meal, replacing the period in $11.99 with a comma. "What about that?" she asks. "Anything wrong with that?"

North Star is one among several Cleveland-area re-entry programs where ex-offenders flock to get an education, housing and employment assistance. It isn't affiliated with Edwins, though employees at North Star have heard about the program and have high hopes for its success.

For many of North Star's members, "taking the GED [test] is their only shot," says program service coordinator Ashly Wells. "But we have some people functioning at a sixth-grade level."

And the GED Testing Service, in an attempt to standardize its program across the U.S. and bring its equivalency requirements up to the level achieved by modern high school graduates, has thrown these former offenders a curveball — the test goes digital in 2014, and triples in price. "I don't feel ready," admits 52-year-old ex-offender Gale Clark, who's taken North Star's preparation course since December. "But I have to take it before it costs more money."

****

Edwins' student application asks the applicant's nationality, educational background and employment history. It's curious about references and military service. It asks nothing about criminal record — Chrostowski doesn't care.

So he leaves that to Passages, another nonprofit workforce development organization that assists ex-offenders in their re-entry into society.

Passages case management director Ardelle Moore and her staff determines whether a person's criminal history is too heinous or too incompatible for him or her to become an Edwins student. The thing is, of the more than 100 people who applied in August alone, only a few were turned away — sex-offenders and people whose past drug addictions aren't quite passed. "They needed to address their substance abuse problems before they will be a fit for Edwins," Moore says. "Then we can refer them back."

The goal is to give as many as possible a shot at the program, which makes the vetting process pretty simple: The first 60 to apply and be approved will become classmates in the inaugural installment of Chrostowski's basement-based school. The rest will be placed on a waitlist.

"It's a great opportunity for others to see the other side of these people, to be able to see that people make mistakes because, really, the only difference between someone that was convicted of a felony or imprisoned and someone who was not is luck," Moore says. "It's chance."

The students will receive a stipend of $200 a month. Chrostowski, meanwhile, will take $50,000 a year. "And I'll cut it if I need to," he says. "Edwins comes first."

****

"It's like it's been waiting for us, like it was meant to be ours," Chrostowski says as he walks through the former Shaker Square Grotto, the intimate space's stone columns giving way to arched doorways and golden walls volunteers will repaint a gray-tinged hue.

"Industrial French," Chrostowski calls the proposed look — a catchphrase that can also be applied to the restaurant's evolving menu, a smattering of French-inspired entrées et plats from rabbit pie to duck à l'orange. "The more description you put on the menu," Chrostowski says, "the less pressure there is on the server."

Despite steady funding sources — Edwins had received more than $200,000 in gift donations from private individuals and organizations by early September, and applied for another $320,000 in grants and loans to fund the school and restaurant — Chrostowski is looking to cut corners.

Leftover high-top tables, acquired in the sale of the space, will be cut down to hip-height by a carpenter, then covered in a sponged vinyl for a high-class kind of look. Pots, dishes, glassware, silverware — anything salvageable will be reused in the gussied-up kitchen and dining room. A local Sherwin-Williams store donated the brushes and paint, applied by volunteers, some of whom may be too young to understand what they're helping to build.

Nine-year-old Mary Cole and her 11-year-old brother, Edward, joined their mother in the weeks after Chrostowski took over the restaurant, cleaning out closets, moving supplies, dusting cobwebs from the windows. "My favorite thing about helping out was thinking that a bunch of people will be getting jobs," Mary says. "It will be good for the prisoners."

Her mother, Anne Cole, agrees. "We're really excited about what this can do for the community," says the Shaker Heights resident. "It won't just be a stellar restaurant. It'll have a greater purpose."

****

Chrostowski is giving a spiel about a final exam to a sea of Grafton Correctional Institution students decked in muted tan and blue jumpsuits, worn copies of the Culinary Institute of America's The Professional Chef stretched in front of them, pens poised, but no one is taking notes — not the older man with graying hair, wire-framed glasses and brand-spanking-new New Balance kicks, nor the grizzly-looking dude with his wedding band tattooed around his ring finger. They're chatting, joking and shouting out answers when they're called to — but the whole scene reeks of a high school classroom filled with students hoping to just skate by.

"Day by day, we do our thing and it works, but this is something I've put a lot of stock into, no pun intended," Chrostowski says of the test that will challenge the inmates to show — on paper and in the kitchen — what they've learned over the last six months, a mishmash of culinary history and math, cooking fundamentals and service.

He launches a review. "If greens cost $3, what do I do with that $3 if I am running 30 percent cost?"

"Divide it by 30," an inmate calls out.

"You're a calculator, man," Chrostowski jokes. He reviews the cost of a carrot peel, voices the five things every kitchen needs by a sink, ticks off a list of seasonal ingredients, and challenges them to memorize how long it takes to boil a chicken stock versus a fish stock.

"Now the red beans and rice," he says. "This is where Jillian comes in, because she's going to tell us how we need to do it."

They come to life. They attack a rack of ingredients, divvying up celery, onions, garlic, jalapenos, green peppers, bacon and packages of Conecuh sausage. "Sometimes they jump right in and it looks like a circus, and it drives me f---ing nuts," Chrostowski says as he stands, arms crossed, a ringmaster observing his performers.

Stainless steel tables and knives — strapped to tabletops with 1 1/2-foot-long metal wires — resemble what you might find in a restaurant kitchen. But that's where the similarities end. Where the prisoners should have saute pans and Dutch ovens, they have 3-foot-wide skillets. And forget anything as high-tech as a hand mixer.

"They don't have enough time. The equipment is bullshit," he says. "At some point, you just have to fight to make it happen."

He spots a heavy-handed inmate mincing garlic. Chrostowski is by his side in three strides, grabbing the white plastic-handled knife from his palms. "You don't want to push all the flavor into the board," he coaxes, rocking the blade over the fresh vegetable himself. "It's porous — it's going to suck up all the good stuff."

****

We're waiting in line to scoop up servings of the too-dry Creole dish onto Styrofoam plates when a prisoner sidles up to my side and asks, "Have you ever been in a prison before?" He waits for my answer, then adds, "We're not all bad people."

Basic human instinct — also known as hope — demands I agree. But basic human instinct also has a self-preservation clause, one that goes something like, but you're in here for a reason. Some of those include murder, vehicular homicide, rape, sexual battery, kidnapping, aggravated robbery, drug trafficking, aggravated burglary, voluntary manslaughter and vehicular assault.

Yet Chrostowski has faith in each and every one of the inmates.

"We've given them a fundamental skill, and it's the right skill," he says. "Then we inject a bit of confidence. Someone shouldn't feel inferior to someone else. And then you hope. You hope they'll make the right call when they get out. They may not remember the right way to peel a carrot, but they might make a good decision in a bad situation. That's success."