The best Christmas I ever had was a Christmas years ago when I was in the Army guarding mysterious and, to me, invisible atomic devices on a base near Albuquerque, New Mexico.

It is hard now to remember what my Army was like. It was the Army that was in use in the Kennedy years after Korea and before Vietnam — a relaxed and pleasant Army which had no plans to go anywhere and nothing to do. Some people I met in it liked it well enough to stay and paid for that decision with their blood in the delta in Vietnam. But most of us were only passing through — lieutenants who had received ROTC commissions with their college diplomas and who were idling away a couple of years between college and career.

My Army was a haven for newlyweds. In the fifties it was considered natural and rather tasteful to get married right after college. We believed in suburbs, domesticity and new Chevrolets. Our brides received Betty Crocker Cookbooks as wedding presents and Revereware pots and other symbols of anti-feminism. We were a generation cozy in a bland society. We didn’t know it. We didn’t think there was anything wrong with it. A lot of us still don’t. But now we are too embarrassed to say so.

If you started marriage broke, the Army would provide heavy mahogany quartermaster furniture and duplex apartments and officers’ clubs where whiskey sours were a quarter, and there was a party every weekend. There was a fitness and a structure to life — the lieutenants glossed their shoes every night with wet cotton balls dipped in shoe polish. The wives became sincerely pregnant. Every New Year’s Day, the officers and their ladies visited the home of the base commander and left calling cards on a silver tray.

If there was a minor annoyance in all this, it was duty. Our duty was not rigorous but it could not be completely ignored. Somewhere on our base people were designing and constructing bigger arid better atomic doomsday weapons. It was our job to protect these craftsmen from interference by spies, saboteurs and tourists who had ridden in on the Sante Fe railroad and might blunder into a restricted area while hunting for turquoise.

The gates of our little base were guarded 24 hours a day. The areas where the fireworks were kept were surrounded by high towers manned continually by sentries. It was lonely and boring work and its chief hazard, startlingly, lay in suicide. If a man had a personal problem, that problem would magnify during the lonely hours of night guard duty. And if the problem magnified beyond containment, the sentry had a pistol on his hip and bullets in the pistol.

The officers did not have to stand guard, but they had to inspect it. About every two weeks one of us would draw 24-hour duty and would spend the night traveling from post to post making certain that the sentries were awake and ready to challenge us. The effectiveness of this inspection system was diluted. Each post had a telephone, and a sentry who had just been checked was expected by his peers to telephone ahead and awaken the sentry at the next post. We officers knew this and the sentries knew we knew it. But it was never discussed. On duty, we college boys struggled to maintain a veneer of dignity and military bearing.

There were reasons for this. In the first place, in those days, atomic weaponry was not treated casually. It was regarded with a mystical and nervous awe the way the Israelites regarded the Ark of the Covenant. The idea that, years later, newspapers would publish directions for the assembly of an atomic bomb would have amazed any of us. We wouldn’t have believed anyone would publish such material. We wouldn’t have believed anyone would want to.

Moreover, we college boys found ourselves in the awkward position of “commanding” sergeants old enough to be our fathers. Sergeants who had been decorated near Inchon and on the Pusan Perimeter while we were trying to get letters in track and baseball and worrying about pledging fraternities. We felt compelled to summon what soldierly bearing we possessed when operating around them and they, in turn, indulged us with a show of respect.

On a certain Christmas Eve, I had drawn the all-night guard duty assignment. The younger officers were stuck with the older holidays. It didn’t matter very much. All of us were far from parents, aunts, uncles and memories of civilian Christmases. On our little base in the desert, we substituted what we could for these amenities. We poured booze and placed candles inside paper bags to form Christmas ornaments called luminaries. And waited for Christmas checks from home.

At about dusk, I strapped on a heavy and (in my hands) largely nonfunctional Colt automatic and rode forth to see what kind of yuletide the infernal machines and their guardians were having. My wife settled down for a forlorn evening with our twin daughters. They were barely a year old, and the Christmas tree (bought from a quartermaster sales lot) had to be displayed on a desk to keep them from pulling it over.

There was a third child on the way. This, when I think back on it now, seems like intense and almost corybantic breeding but at the time and among my peer group it was not unnatural. We believed in fulfillment through families just like on Father Knows Best.

If I had known better, I would have tried to swap my Christmas duty with another young lieutenant. But a doctor had assured us that my wife’s delivery was still weeks away. So, when several hours later she phoned headquarters and told me she thought she was going to have the baby any minute, I tried rationally to argue her out of it.

“You thought that last time and you were off by a week,” I said.

“That was last time,” she said. “This time I’m sure.”

“But my God,” I said. “How am I gonna get over there? What am I gonna do about all these bombs?”

“You just better come,” she said.

The sergeant on duty with me that night was a Sergeant Taylor, whose chest was as bright as a Christmas tree with ribbons won in history book engagements. He politely pretended to ignore my end of the conversation and busied himself with paperwork as I called the officers’ club and paged my friends — all of whom came to the phone drunk and disorderly. Full of congratulations and rum punch. Willing to work but unfit to do it. Taylor audited these conversations and then, with measured deliberation, cleared his throat and joined me in my problem.

.

.

“Something wrong, Sir?” he said.

“You heard most of it,” I said glumly. “My wife is sitting home in labor. My friends are all loaded. My neighbors are out. If I take my wife to the hospital, I won’t be able to find anybody to babysit the twins. I don’t know what to do.” Taylor looked at me thoughtfully.

“Well,” he said. “Why don’t you use one of the guards?”

“How can I do that?” I said. “Who?”

“My choice would be Buck,” Taylor said. “He’s on the North Gate. He’s probably sleeping anyhow.”

Taylor’s remark lifted our conversation to heights of candor previously unscaled.

“You know Buck,” Taylor said, quietly. “He’s been busted twice in the last year. He’s always in trouble and he’s in trouble now. Never mind what kind of trouble. I know about it. If you used one of the other guys, the word would probably get around. Buck will keep quiet. He probably won’t even know there’s anything wrong with it. He hasn’t figured out the Army yet.”

So I did it. I pulled Buck off the North Gate and put him in my living room. I told him to make a pot of coffee and to call if a twin awoke and a bottle of formula wouldn’t quiet her. I drove my wife to the base hospital, kissed her encouragingly and burned rubber getting over to the North Gate to see if there was any sign of the Russian army on the horizon. There wasn’t. All was calm. All was bright. Then I heard Taylor’s voice on the radio.

“Whyn’t you come back, lieutenant,” he said. “You got a new boy.”

“What about the Gate?” I asked.

“Bullshit!” said Taylor. “C’mon back. We got something for you.”

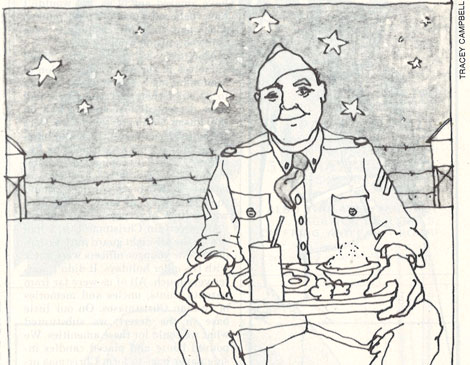

He had sent over to the mess hall and had them fix a tray of breakfast — a good Army breakfast with eggs swimming in grease and big slabs of bacon. Creamed chipped beef and French toast, fried potatoes, juice and coffee. He handed me the tray like a gift and for some reason it touched me as if he were offering something precious. Years later I decided that it probably was because, when your first son is born, it is good if your father is there and mine wasn’t. Mine was a thousand miles away asleep and Taylor, who was old enough to be my father, was, in a way, substituting for him as he had, I suppose, a hundred other times with somebody’s son in unusual and far worse situations.

He grinned at me. “Congratulations and Merry Christmas,” he said. And I thanked him and took the breakfast tray but under the desert stars.

The stars hung close that night and the sky was tuxedo blue. I had a son and that changes a man, and I felt myself changing right there and it was a bittersweet feeling.

The stars hung close that night and the sky was tuxedo blue. I had a son and that changes a man, and I felt myself changing right there and it was a bittersweet feeling.

Taylor and Buck are long gone from my life and I couldn’t send them a Christmas card if I wanted to. It isn’t necessary. We were not friends really. We were just partners in a moment of humaneness on a base built to manufacture destruction. I wish them both well every year and hope nothing happened to them in the war that filled the long years since that night.

Each December as Christmas moves away in time, I think of it and decide that it was the best Christmas I ever had. The memory of it is a talisman for me of many things — all good. And sharing it with you is the best I can do in the way of offering every good wish for the holiday season.

This story originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's December 1979 issue.

Each December as Christmas moves away in time, I think of it and decide that it was the best Christmas I ever had. The memory of it is a talisman for me of many things — all good. And sharing it with you is the best I can do in the way of offering every good wish for the holiday season.

This story originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's December 1979 issue.