Cleveland TinType Brings New Life to Old-Timey Photography

by Annie Nickoloff | May. 9, 2023 | 12:00 PM

Courtesy Paul Lender, Courtesy Joseph Brown, @josephwymanbrown

When Paul Lender shows up for a pop-up photography event, it’s a little bit like a circus sideshow.

He lugs an 80-year-old Burke and James Commercial View Camera (an old-school, folding camera with an accordion-esque extension) into a venue like Lakewood’s GoodKind Coffee or downtown Cleveland’s Rebuilders Xchange, and sets up a small studio space.

A customer shows up for their allotted time, and poses. Lender carefully focuses the camera and, once things are fine-tuned, clicks the camera’s shutter for a long exposure, capturing the image on a light-sensitive plate. Then he dips the plate into a mix of chemicals, revealing and properly exposing an image, before washing and sealing the photo. Over the span of 15 minutes, Lender produces one singular portrait.

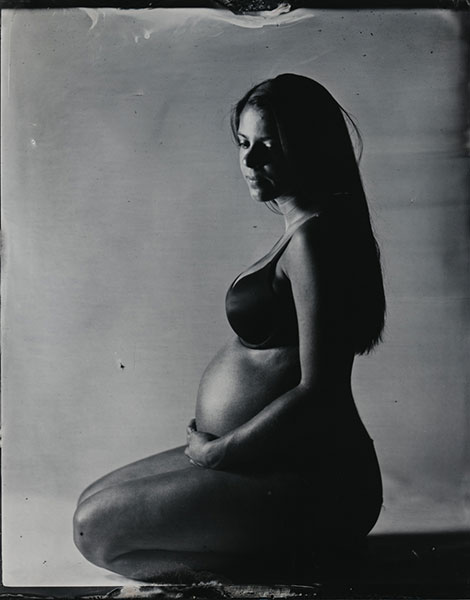

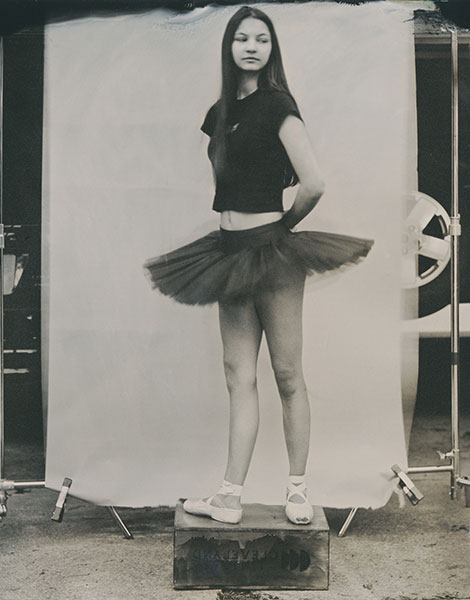

The wet plate collodion process, in action: Lender showcases the science live, and produces high-resolution images that are, at their heart, one of a kind.

At these three or four annual pop-ups and through commissions, Lender has helped to make a 170-year-old photography process a current part of Northeast Ohio’s photography world. Welcome to Cleveland TinType.

Lender is one of just a few photographs in the region who was drawn to tintype photography, and one of the only to host pop-up style events for customers to purchase his work. Greg Martin also uses the wet plate collodion process for many of his portraits, while Michael Rhodes creates tintypes partly through his involvement in the Civil War reenactment community.

“The appearance of them is so unique; I think people are very attracted to that one-off, ‘it’s gonna last forever’ appeal,” Lender says about the format. “Some people say it’s the most honest photo of themselves that they’ve ever seen.”

Pandemic Beginnings

Lender, a full-time biologist at Avery Dennison, grew up taking photographs for Willowick Middle School's photo club and, later for Eastlake North High School's yearbook and student newspaper. He returned to the photography hobby on the side in 2008 with his Left of Center digital photography brand, focusing on portraits, senior photos and weddings. Despite that digital focus, he was interested in tintype photography and, in 2012, even acquired a large-format camera to try it. It wasn’t until the pandemic that he decided to dive in.

“Like everybody else in photography, you got shut down. You couldn’t do inside sessions, you couldn’t do outside sessions. My kids’ activities got canceled, so I wasn’t hauling them around to ballet classes and things like that,” Lender says. “I had all this time, and I was like, ‘Well, let’s finally figure out this tintype thing.’”

Following a few phone calls to fellow tintype photographers, and hours and hours of YouTube videos, Lender finally gave the wet plate collodion process a try — a “disaster for about the first month or so.” The process involves mixing iodine with collodion, a sticky nitrocellulose material, to then coat a plate, which is dipped into silver nitrate to create a light-sensitive particle on the plate: a wet type of film, which is then developed with other chemicals.

After plenty of trial and error, Lender finally managed to figure out the formulas and how to properly expose his tintype images.

Then he decided to offer tintype photo sessions to the public, never expecting them to take off. At his pop-ups, Lender charges $75-$95 for tintype photographs, depending on the size.

“I had no plans whatsoever of generating income from the wet plate collodion process,” Lender says. “I figured it would be a very easy process to keep as a hobby because I didn’t think anybody would want to pay for it — and it turns out that quite a lot of people want to pay for it.”

Sense of Timelessness

Looking at Cleveland TinType’s Instagram, and you’ll see vibrant black-and-white eyes peering at you; chemical swirls and flecks of dust adding textures to background panels and wrinkles and smiles. Moving subjects are captured in a swirl of blur.

The imperfect, in-the-moment nature of tintype photography gives it some of its charm, Lender says.

“Every time I pour that chemistry, something a little bit different is going to happen,” Lender says. “Every single one of them is going to be different; even if I keep you standing in the same spot in the lights, there’s always that artful creation of it that’s just a little bit different.”

It’s a far cry from Left of Center’s carefully composed photographs, but it brings a creative challenge to Lender’s photography life. And, unlike digital photography, tintypes are inherently built to last and to be seen, in-person.

“A digital photo lives in a digital camera, bits and bytes on an SD card. You drop it on your computer, you maybe edit it, you post on Instagram or Facebook or TikTok or wherever, and it might never really exist beyond that, except on your phone when you show it to somebody,” Lender says. “There are tintypes from 170 years ago; there are still thousands and thousands of them. You hope that the same thing happens with the ones we’re making today.”

Lender plans on hosting his next Cleveland TinType portrait pop-up this summer. Interested customers can sign up for appointments ahead of time, once it is announced; he suggests following the Cleveland TinType Instagram or checking out his website, locphoto.com/popups, for details when they become available.

Annie Nickoloff

Annie Nickoloff is the senior editor of Cleveland Magazine. She has written for a variety of publications, including The Plain Dealer, Alternative Press Magazine, Belt Magazine, USA Today and Paste Magazine. She hosts a weekly indie radio show called Sunny Day on WRUW FM 91.1 Cleveland and enjoys frequenting Cleveland's music venues, hiking trails and pinball arcades.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5