The article is published as part of an exclusive content-sharing agreement with neo-trans.blog.

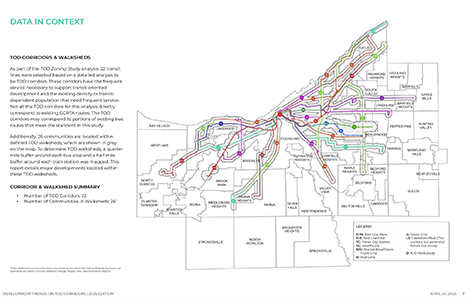

An annual report by the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission released this week showed that Transit Oriented Development in the county reached an all-time high in 2024. But 92 percent of countywide TOD activity is occurring in the city of Cleveland. And only four of 26 communities along high-frequency transit routes and walksheds, called TOD corridors, had a TOD project in the past six years indicating a lack of suburban activity.

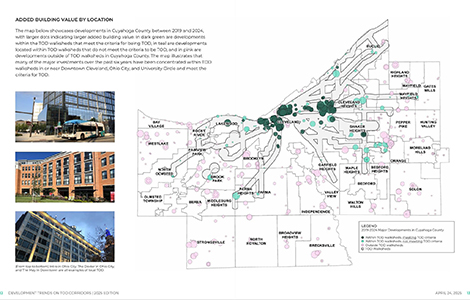

In the period 2019-24 inclusive that was tracked by the commission, $1.2 billion worth of TOD development among 150 projects occurred in Cuyahoga County, averaging $199 million per year. Among projects adding $1 million or more of building value, only about one-third of these were TOD projects in TOD corridors countywide.

“We’re excited to be able to produce this report,” county Planning Manager Patrick Hewitt told NEOtrans. “What is exciting for us is to see that the value of TOD investment has been increasing each year since 2021, reaching a high of $298 million in 2024.”

He noted that this is the third annual report. But a new feature in this year’s report was the county’s review of the design of all of the projects to determine if they met basic criteria to qualify as TOD, he said.

So just because a new construction or renovation project occurred within a walkshed of a high-frequency transit route doesn’t mean it qualifies as TOD. The commission says a qualifying TOD project is close to the street, has multiple stories, parking located to the side/rear, TOD-friendly use/mixed-use, and a front-facing building entrance.

A high-frequency transit route has a bus or train scheduled in each direction every 15 minutes or more often on weekdays. TOD walksheds are areas within a quarter-mile of each bus stop and a half-mile of each train station.

TOD investment accounted for 33.6 percent of total added building value in Cuyahoga County in the past six years. But in TOD corridors, TOD investment accounted for 64 percent of added building value. In Cleveland, it was 84 percent with most of it happening in Downtown, University Circle, Ohio City, Hough and Tremont, in that order.

But only Cleveland, Cleveland Heights, Lakewood and Shaker Heights had TOD investments occur in their communities since 2019, despite 26 Cuyahoga County communities having TOD corridors. It indicated either a lack of interest or awareness about TOD. The commission sought to address both with this report.

“Our goal with this report is to understand TOD investment over time and showcase the expansion of TOD in Cuyahoga County,” Hewitt said. “Ultimately, we would like to see this type of development embraced across TOD corridors to make taking transit to and from work, home and other destinations easier.”

Greater Cleveland has made a huge investment in transit. If it was to build its rail rapid transit system from scratch today, it would require a $4 billion investment, said the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority.

It continues to invest in that rail system with a $450 million railcar replacement program plus many other capital projects. It also is expanding its bus rapid transit system with its MetroHealth Line on West 25th/Pearl.

According to the Federal Reserve in Cleveland, fewer than one-third of all jobs in Greater Cleveland are accessible within a 90-minute one-way transit trip. The physical disconnect between jobs and job-seekers is a big reason why this region has such high poverty while thousands of jobs remain unfilled.

“To that end, we have provided best practices and model TOD zoning for communities, all of which are available online,” Hewitt added. “We are presently working on the fourth element of our TOD zoning initiative, which explores financing and incentives that can support future development.”

Cleveland recently adopted a Transportation Demand Management policy which developers can use to build TOD-themed projects that reduce the amount of parking they have to build, thereby reducing the costs of construction and improving the chances of delivering a project.

“Parking is always the thing that, in a lot of ways, economically destroys the ability to get a deal done,” said Dan Whalen, principal at Places Development, last week while seeking city approval for a new hotel in Ohio City.

The cost of building and maintaining parking represents an increasingly significant share of housing expenses. City-enforced parking minimums can add $1,700 a year in rent for the average tenant. And government subsidies are often needed to help make development projects economically viable, thus externalizing the cost of driving.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.