Plans for New Clinic Garage Ignite Call for Better Transit Options

Transit groups urge healthier, sustainable options amid plans for a new Cleveland Clinic garage on the former site of the Cleveland Play House.

by Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans | Nov. 18, 2024 | 7:00 PM

Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans

The following article was published as part of an exclusive content partnership with neo-trans.blog.

The largest structure on the Cleveland Clinic’s Main Campus isn’t the new 1-million-square-foot Neurological Building on Carnegie Avenue. Instead it’s the 1.56-million-square-foot East 89th Street Parking Garage just west of the Neuro Building. And immediately west of that, on the former site of the Cleveland Play House, Clinic officials are reportedly considering another large parking garage that has transit advocacy groups calling for healthier options.

It’s a part of the growing pains experienced by the Clinic and its neighbors. Those pains include having to build the costly parking decks, Clinic employees having to park on residential streets, worsening traffic and air pollution, plus sedentary lifestyles from car dependency and not enough walking. The $331 million, 3-mile Opportunity Corridor was beset with traffic jams the day it opened in 2021 and has only gotten worse, commuters tell NEOtrans.

Car dependency is as much a function of land use design as it is a function of a lack of transportation choices. There is a lack of housing within walking distance of the Clinic’s Main Campus although that’s improving. And there are limited public transportation services which is not improving. Meanwhile, the University Circle-Fairfax area is challenging Downtown Cleveland for Ohio’s top employment hub yet its transit options are far fewer than downtown’s.

Two sources who spoke to NEOtrans on the condition of anonymity said the Cleveland Clinic will hire an engineering firm next year to design a “big” parking garage on the 11.3-acre ex-Cleveland Play House site, 8500 Euclid Ave. NEOtrans broke the story that the Clinic would demolish the former Play House structures after America’s first professional regional theater relocated in 2011 to the Allen Theater at Playhouse Square in Downtown Cleveland.

“We are currently evaluating options and have not made any final decisions regarding this project,” said Angela Smith, senior director of corporate communications at the Cleveland Clinic. “Given the growth of our campus, we need additional parking for our patients and caregivers.”

In fact, two years ago, the Clinic was weighing the potential construction of two additional parking garages. It was getting a $1.3 billion construction program underway that would primarily focus on major developments at its Main Campus near Cleveland’s University Circle. To prepare for that program, the Clinic conducted a traffic and transportation study with the aid of data from the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency. The study was not made public.

The Play House-site deck would provide additional parking for the new Neuro Building and its 2,000 workers plus visitors as well as future development on the rest of the Play House plot of land. The 4,000-space East 89th Parking Garage next to the Neuro Building is often nearly full.

Cleveland Clinic’s Executive Director of Buildings & Design Jorge “Pat” Rios told NEOtrans at the time that he did not like having to build so many garages due to their high construction cost and their ongoing operating costs. The Clinic’s most recently built deck is the East 105th Street Parking Garage at Cedar Avenue.

The 3,000-space, nine-level, 915,000-square-foot garage on East 105th cost $38.5 million to build a decade ago, according to Desman Design Management of Cleveland. Inflation calculators show it could cost more than $50 million to build a similar garage today. But construction materials have gone up in price faster. NEOtrans’ two sources say the Clinic’s next big garage could cost up to $100 million to build.

Growing pains experienced by the Clinic affect surrounding areas. City Council President Blaine Griffin’s Ward 6 includes the Cleveland Clinic Main Campus from Chester Avenue into neighborhoods farther south including all of Fairfax. He said he often hears residents’ complaints of Clinic workers parking on their side streets and passes those concerns on to Clinic executives.

Clinic officials in the past couple of years, for the first time, partnered with developers on building housing near campus so more workers could move closer and walk or bike to campus. The result was the Aura at Innovation Square and the Medley at Fairfax Market — both on East 105th.

The latter was built on Clinic property. But while both projects have phase twos in their plans, neither has advanced to the city for approval. Other projects are advancing. Hundreds of housing units are under construction in the University Circle area and more are planned.

Transit advocates say the Cleveland Clinic and the city’s “Second Downtown” is underserved when it comes to public transportation. In fact, University Circle-Fairfax is already rivaling Downtown Cleveland as the region’s primary employment hub. To show University Circle is underserved, they compare public transit route maps of downtown and University Circle.

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority Public Information Officer Robert Fleig did not respond to two e-mails from NEOtrans seeking comment for this article.

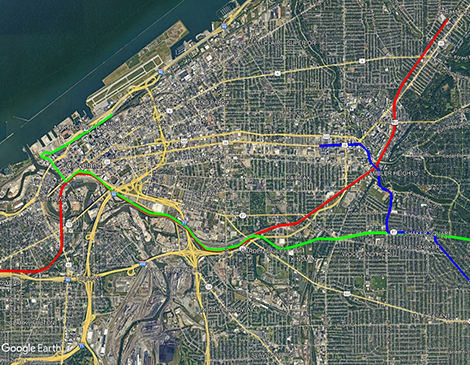

Yet downtown is served by three rail lines extending out in five directions from Tower City Center. plus the HealthLine bus rapid transit (BRT) on Euclid Avenue, a BRT-light on Clifton Boulevard, and a planned, partially funded BRT-light on West 25th Street. The only planned transit expansion for University Circle is an $80 million BRT-light called Thrive 105-93 but has stalled over the past seven years and would likely not have increased service frequency.

No rail line serves the heart of University Circle and instead skirts the southern and eastern edges of it. The nearest Red Line stations are 1 mile from the heart of the Clinic at Euclid and East 93rd Street. There are no plans to expand the Clinic’s Main Campus nearer to Red Line stations. Instead, it’s expanding in the opposite direction.

The HealthLine BRT serves the Clinic. But since it began in 2008 after a $200 million investment, service frequency has fallen from every 10 minutes to 15 minutes and bus travel times have slowed 33 percent. HealthLine ridership fell from 5.1 million to 1.7 million over the past decade, Clevelanders for Public Transit complained.

Some have urged the Clinic to provide subsidized GCRTA transit passes for workers and even for patients. In Columbus, each downtown-based employee gets a free transit pass as part of their fringe benefit package while many are required to pay for parking. For Clinic visitors, a free smart payment voucher could be provided when making appointments online or in person, transit advocates suggest.

Also, advocates are urging that one of the two light-rail services from Shaker Heights be rerouted away from downtown and instead go to the Cleveland Clinic. In the 1990s, the HealthLine BRT was originally planned to reroute the three Rapid transit lines — the Red Line and the Blue/Green Lines — down Euclid from University Circle to downtown.

The $700 million “Dual Hub” project, including a 1-mile downtown subway, was deemed by the suburban-dominated board of the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) as too expensive. NOACA administers federal funding for regional transportation and air quality programs. A compromise resulted in the construction of the HealthLine BRT.

“Why do we default to car-centric solutions when the University Circle area is already awash with traffic?” said Bill Hutchison, a spokesman for the Lakeshore Rail Alliance, a coalition of rail passenger nonprofits from Chicago to New York. “We believe there is a need to diversify our transportation options and that should include extending the Blue Line into the area.”

Brian Schriver, the Northeast Ohio director of one of those nonprofits, All Aboard Ohio, suggested that the Clinic use the funding it intends spend on new parking garages and instead put it toward the local funding share for extending the Blue Line to its campus.

GCRTA is acquiring standardized rail cars that will be able to go anywhere GCRTA has track. So a train from Cleveland Hopkins Airport could also travel right to the Clinic’s front door, for example.

“The new transit option would be transformational for the region, and $100 million would provide a substantial share of the necessary local match to make this Blue Line connector happen,” he said. “Imagine having an easy trip to the Clinic’s Main Campus from anywhere on the Rapid system. Getting more people on public transit encourages walking which improves health outcomes. All of these outcomes are aligned with the Clinic’s goals.”

“We are open to community dialogue and look forward to navigating the public process for this project when appropriate,” Smith responded.

Schriver also pointed to other community benefits, including a direct rail link between University Circle and Shaker Square which is seeking to redevelop itself with more modern housing, more hospital and university employees living there, and new neighborhood retail and other businesses.

“Even drivers would benefit as every person taking the Rapid to the hospital is one less car driving in the area,” Schriver said. “All of this can be accomplished with just two miles of new light-rail infrastructure.”

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Ken Prendergast, NEOTrans

Ken Prendergast is a local professional journalist who loves and cares about Cleveland, its history and its development. He has worked as a journalist for more than three decades for publications such as NEOtrans, Sun Newspapers, Ohio Passenger Rail News, Passenger Transport, and others. He also provided consulting services to transportation agencies, real estate firms, port authorities and nonprofit organizations. He runs NEOtrans Blog covers the Greater Cleveland region’s economic, development, real estate, construction and transportation news since 2011. His content is published on Cleveland Magazine as part of an exclusive sharing agreement.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5