The dollar bills all say “In God We Trust,” but we don’t. We certainly don’t trust the stability of the dollar bills. We don’t trust much of anything if the truth be told. Don’t trust the politicians, don’t trust the newspapers. A lot of us used to trust Ralph Nader when he was an underdog but when he got to be a sort of conscience conglomerate, our trust waned.

Perhaps, e pluribus unum, the thing we trust most is statistics. Demographics and polls. Ratings and surveys. Records. As long as they seem official, we seldom question them. We cheerfully contribute to them as a sort of national duty. Buy an electric appliance these days and, attached to the warranty card, we are apt to find a personal questionnaire asking us how much we make, what our pleasures are, how we spend our money. A question on the card asks us if we mind if this information is shared with others and suddenly we are on a new mailing list. A mailing list that is more than a mailing list. A mailing list that is a mini personal history.

Often blindly, we believe in records and statistics. In Vietnam, in 1970, the statistics could still be made to show we were winning the war. We could not seem to win any terrain and in the rice paddies and on the forested slopes near Da Nang the war was going badly. But the computers were enjoying great victories — enemy body counts mounting up nicely, thank you. Enemy supplies projected to be far less than necessary. The war of the computers was going far better than William Dinger’s war was going.

William Dinger, in the Marines, in the infantry, was having a nerve-wracking war. A literally nerve-wracking war that wracked his nerves so badly that the government labeled him a disabled veteran and sent him to the Brecksville Veteran’s Hospital to recuperate. This column, however, is a story about William Dinger’s peace.

When Dinger had recovered sufficiently, he took an apartment in Brecksville and set out to find a job. His quest took him first to Joe Andry, a counselor with the Veteran’s Administration, then to Robert Wallace of the Ohio Job Service, a former Marine Corps officer whose job it is to find work for disabled veterans.

“When he came in here, he was willing to take anything,” Wallace recalls. “He had had some trouble getting jobs. He would go out for interviews and things would look OK. Then he would be notified that the position had been filled. Sorry. That’s all. No reason.”

Wallace and Andry both were sympathetic. They had been through it before. They knew the job market was tight and they knew that Dinger would probably be hurt and frustrated by his lack of success. So they did their best to cheer him up and to line up openings for him.

But things didn’t get better. In fact, they got worse. Dinger was hired by one company, only to be called in a few days later and told there had been a mistake. There was no job after all. That experience, devastating as it was, marked Dinger’s pinnacle of success. Wallace sent him for other job interviews — interviews that looked like sure things — and the story was the same. Conversation with a personnel director, a flurry of hope, then a phone call. Sorry, the position has already been filled.

This went on for a year and in that year, Dinger was rejected almost a dozen times. He grew more depressed, spent more time back at the VA hospital.

Wallace shared Dinger’s frustration. He couldn’t understand Dinger’s failure which, in its way, was his failure as well. Finally, he called one of the employers who had rejected Dinger. “Look,” he said. “I can’t believe this. Just what’s the matter with this guy?”

The employer told him. Wallace listened in consternation.

“Your man’s got a record a yard and a half long,” Wallace was told. “You ought to know better than to send a guy like that over here. Name it, he’s done it. Misdemeanors, felonies, armed robbery, a stretch in jail, violation of parole. He’s got thirty counts on his record.”

“I called Dinger in,” Wallace says. “I told him he had better level with me. I told him if he were lying to me it wasn’t helping him and it wasn’t helping me. He swore his record was clean.”

So Wallace checked Dinger’s record himself. Carefully. And he found that the William Dinger with the yard and a half record was nearly a foot shorter than William Dinger, ex-Marine. Somewhere in the process of filing and storing information, William Dinger, it seemed, had acquired another man’s criminal record.

Wallace isn’t sure how. Nor is Dinger. Some years ago, Dinger lost his wallet with identification and social security card. Did the crook with the record find it and assume Dinger’s identity?

Far more interesting is speculation about those employers who turned Dinger down. Did they, in violation of regulations, have access to offical police records? Did they see Dinger’s record, automatically trust it and just as automatically reject him without telling him why? Everybody’s guess is that this is exactly what happened.

Most of us know that somewhere — in several places — there exist file cards, computer readouts, dossiers which contain personal histories on each of us. A piece of information here, a piece there. Swapped, crosschecked, stored.

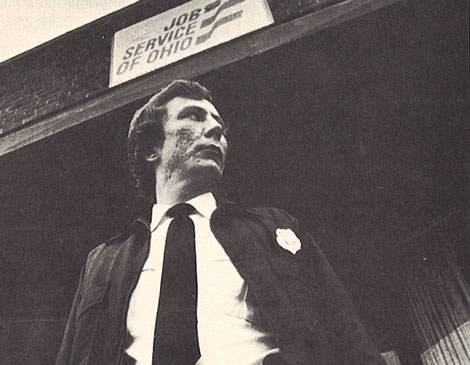

Perhaps it is worth our while to wonder at least what the records show about each of us. And to wonder also just who has access to bits and pieces of our lives that may have been assembled in a way that would make us uneasy. As uneasy as William Dinger’s peace was before he finally got a job. As a security guard for the state of Ohio.

This story originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's April 1979 issue.