Life of the Party

by Erick Trickey | Aug. 20, 2009 | 4:00 AM

Hundreds of people — union leaders, Cleveland city officials, suburban mayors and councilpeople, grassroots Democratic Party members, county contractors, even Republicans — came to see him at his last campaign fundraiser, an immense Sunday brunch two Octobers ago. They all waited in a line that stretched across Executive Caterers at Landerhaven’s glassy lobby, just to shake his hand. Like a proud father of the bride, he greeted every one of them with a joke, a smile, a slap on the back. He knew them by name, had gone to their parents’ funerals, their kids’ birthday parties, their own campaign fundraisers, their charity events.

“It was Jimmy at his best,” remembers Gary Norton, East Cleveland City Council president. “Smiling, funny, outgoing and loud.”

The party matched Dimora’s generosity and appetite.

The $80 tickets were a bargain on the political fundraiser circuit, considering what you got: crisp bacon and sausage, blintzes in blueberry sauce and chef-carved Boston strip roast — a dish Dimora himself had insisted upon. Big-screen TVs showed the Browns game (Dimora knew not to ask Clevelanders to choose between brunch and football). The party cost Dimora almost $25,000 to throw, but it made him $61,000.

Dimora spoke, though only to introduce his allies big and small. “I don’t think he ever mentioned it was a fundraiser about him,” says Norton. He mixed thank-yous to labor leaders and precinct committee people with good-natured repartee with Cleveland’s congresspeople, dubbing the late Stephanie Tubbs Jones his “girlfriend” and “the hottest member of Congress.”

Afterward, Dimora stood offstage. He didn’t have to work the room. The room worked him.

People genuinely liked Dimora, the monument-sized guy with the cement-drill voice, always quick to laugh and make them laugh, who asked about their mom or spouse or kids. “[He made] you feel you were never anything short of fantastic,” a frequent guest says.

That’s what gave Dimora his power.

“That’s how to be a blue-collar guy who has the ability to influence whether or not lawyers become judges and doctors become coroners,” Norton says.

That gregarious side of Jimmy Dimora went into hiding last summer after the FBI raided his house and office. In his place is a Dimora who hides his anxiety behind silence, subduing his brash, loud instincts until heavy black headlines and cries for his resignation provoke his fury.

That’s the Dimora Cleveland saw in his now-infamous June press conference. Scowling, sweating, his already loud voice amped up to an explosive whine, he blamed the FBI corruption investigation on an unlikely cabal of enemies: Karl Rove, The Plain Dealer, Ohio Republicans, Cuyahoga County reformers, the U.S. Justice Department (under both presidents Bush and Obama). “It’s all a conspiracy,” he said.

Dimora spent one minute declaring his innocence and 13 minutes counterpunching and score-settling, showing Cleveland his temper, hyperpartisanship and sense of persecution.

But none of those traits explain why he’s in trouble.

“You may not like me personally,” he said to introduce himself that day. “You may not like my politics, you may not like my size — being overweight. You may not like my ethnicity. But sometimes, you have to fight fire with fire.”

The truth is, though, people are fond of Jimmy Dimora —lots of people. Dimora reigned for a decade as Cuyahoga County commissioner and Democratic Party chairman because of who he is. He stood out in a field of gray suits (even when he wore one) as the friendliest and funniest guy in local politics, the guy who showed up everywhere and cracked up crowds with outrageous jokes no one else could get away with.

That side of Dimora, not a caricature of angry arrogance, may be the key to understanding how he became a target of a federal corruption investigation. It may also explain why he insists he is innocent and, when asked at the press conference if he’d done anything wrong, he replied, “I’m not an angel, but I’m no crook,” and added, “I’m not doing anything different than any other public official does.”

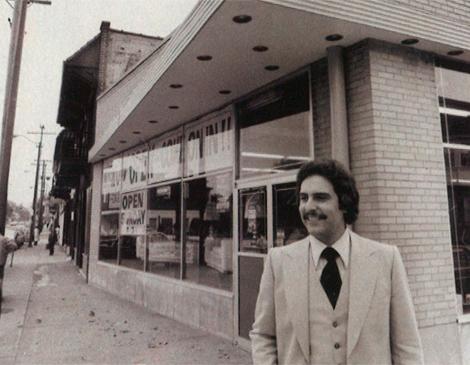

Photo Caption: In fall 1977, Dimora, age 22, launched two ventures: He opened a furniture store on Cleveland’s East Side and ran for Bedford Heights City Council.

Dimora declined to talk about his career for this story. “Right now’s not the right time,” he said.

But friends, allies and rivals have offered insights into how Dimora has approached politics, friendships, favors and connections throughout his 32 years in public office. Their accounts may help explain how Dimora got into trouble — how the most social of leaders, a guy who rarely said no to an invitation, who made deals over restaurant tables, who knows every political figure in town and what they want, who’s built a career on connections and loyalty, might have said yes to too many gifts, may have put in a good word for too many people and may have nudged and then lumbered his way over a line that he still doesn’t think he crossed.

There are two stories about how Jimmy Dimora got his start in politics. One is set in the early 1970s in Bedford Heights’ old City Hall, where a high school student named Jimmy Dimora, a steelworker’s son, swept the floors. He was a part-time custodian, a job that included setting up the chairs for meetings. It gave him an idea. “It was where the action was. Stuff was being decided,” he told The Plain Dealer in 1998. “I liked it.”

It’s a good story, but Dimora usually tells a better one built on called-to-duty symbolism and bootstrapping determination. He likes to say he became mayor by falling into a vat of shit.

Jimmy graduated from Bedford High School in 1973 and, rather than attend college, got another city job: wastewater plant operator. One day, under lights dimmed to cope with that year’s energy crisis, he slipped on a loose catwalk and fell into a sewage vat. He grabbed the side with one arm to keep himself from drowning. Hanging there, sewage up to his knees, he imagined his parents getting the humiliating call telling them how he died.

Once he climbed out, he got mad. Nursing a torn-up knee, 18-year-old Jimmy limped to City Hall, asked for a meeting with Mayor Lucille Reed and told her that her policy of turning lights off to save energy had made the plant unsafe. Reed — age 47, mayor for seven years, whom Dimora later described as “a domineering person who has ruled with an iron fist” —turned furious.

“If you don’t like the way we’re handling things in this city,” she said icily, “you run for mayor.”

Reed must’ve meant it as an insulting squelch: Who does this kid think he is, talking to me like that? But the cruel irony bounced right off Dimora. Becoming mayor was exactly what he wanted to do.

Four years later, in 1977, after a year of community college business classes, the 22-year-old Dimora launched two ventures: He opened a furniture store and ran for Bedford Heights City Council. At Furniture King on Cleveland’s Buckeye Road, he sold couches; back home, going door to door on Sweet Birch Drive and Meadow Lane, he sold himself. He discovered something Reed would’ve thought absurd: Who he was didn’t disqualify him from power — it made people want to give it to him. Dimora later boasted he knocked on every door in Bedford Heights, a town of 12,000. He won.

Mayor Reed hated Dimora, the brash upstart with the big smile and long sideburns. She didn’t invite him to council’s swearing-in ceremony, so he went public with the snub, getting headlines in both Cleveland papers. Two years later, Dimora ran to unseat Reed. The old guard mocked him: He was 24, still living with his parents, and he wanted to run the town?

Dimora lost. But after that, he grew up fast. He married his high school sweetheart, Lori, and they bought the little ranch house with a bay window where they would raise a daughter and two sons. They could see the brand-new, sleek, brown-brick City Hall from their front door.

Reed retired in 1981, letting Dimora know he wasn’t invited to the goodbye party and tapping another councilman, Robert Furlong, to succeed her. Dimora ran against Furlong, knocking again on doors across town. He won soundly. Elected mayor of Bedford Heights at age 26, he kept the job until he was 43.

Dimora’s across-the-street neighbor, Catherine Hicar, remembers stopping him on his walks home from City Hall to tell him about city service problems. He didn’t mind. “He was very personable to everybody,” she remembers. “You could call him anytime.”

Dimora “stood by his word,” Hicar adds. He’d promised to build a recreation center — a place to play basketball, racquetball, bingo, to swim and shoot pool — and got it done in three years with no new taxes. When he left for the county commission, the new mayor named it the Jimmy Dimora Community Center.

For 17 years, Dimora was Bedford Heights’ unchallenged leader. A 1988 poll said 86 percent of the town thought he did a good job.

He started getting to know Democrats throughout Cuyahoga County. He knew how to bring people together: He hosted softball games between his City Hall’s employees and county workers. He was the pitcher, a good athlete, at the center of the diamond and in control.

He didn’t have to announce his ambition. People could tell.

“I think he had a goal to be party chairman,” says former U.S. Rep. Mary Rose Oakar. “I’d see him at Democratic events, at parties, wherever I campaigned, wherever I went.”

Dan Brady, then a Cleveland city councilman, remembers driving out to Bedford Heights in 1990 for a rally Dimora organized for Democratic candidates. Brady wanted to see what the up-and-comer had going for him. The answer was a style like no one else’s. Dimora, his voice filling the big gymnasium like P.T. Barnum, made politics a fun-filled carnival.

“It was a throwback,” Brady says. “I felt like I was watching something from another era, the ’50s.” When Dimora introduced the candidates to the working-class crowd of a few hundred, his message was “standard Democratic Party cheerleader stuff,” Brady recalls, but his delivery was filled with an entertainer’s flair and corny humor. “He had a vaudevillian persona,” like “a political rally ringmaster,” Brady says: “the big guy at the center of the ring with the booming voice who tells you what the next act is.”

In 1992, Dimora tried to move from emcee to star attraction. He and Brady ran for the same seat on the Cuyahoga County Commission. Dimora wasn’t as well-known as Brady or the other main candidate, state Sen. Jeff Johnson. He needed tens of thousands of votes, but he tried to win the way he knew best: one Democrat at a time. “He was working very hard on the ward leaders and on the party insiders in a way that I was not,” Brady recalls. “At meetings, he would be huddled with some officers from the clubs.”

Dimora’s many alliances would make him the county Democratic Party chairman two years later. But in the race against Brady and Johnson, some of his tight friendships and alliances hurt him. The Plain Dealer poked around Bedford Heights and asked why the city paid thousands of dollars a year to have the jail’s prison uniforms laundered at the Proud Pony, a bar near City Hall owned by a Dimora campaign contributor. (After the paper requested records, Dimora reportedly had an employee price a washer and dryer for the jail.) Another story said Dimora had accepted almost $15,000 in donations from city employees and hadn’t reported them correctly, and that he’d written a letter in support of Bedford Heights’ former trash hauler, who had twice been convicted of theft. Johnson won with 71,000 votes, compared to Dimora’s 62,000 and Brady’s 61,000.

On Valentine’s Day 1998, more than 400 Democrats walked into a banquet room at the Holiday Inn Rockside in Independence that was half-lit by a dim chandelier and smelled of day-old cigarette smoke. For a Saturday morning meeting, the staff had put out too many doughnuts and not enough coffee. Instead, dozens of candidates provided the buzz, hand-shaking, asking for votes, vying for endorsements for the state legislature and judgeships.

As the Democrats sat in the room’s too-many chairs, they looked around and saw their party’s cliques and factions. Their biggest vote of the morning threatened to divide them further. They had to decide whom to endorse for county commissioner: Jimmy Dimora, the county’s party chairman, or Pat Sweeney, a state senator with lots of powerful campaign donors.

Another divide was also on their minds: black and white. U.S. Rep. Louis Stokes had accused the party of not nominating enough black candidates under Dimora’s leadership.

“Everyone was kind of tense,” recalls one Democrat. But Jimmy Dimora strolled toward the stage asking people how they were doing, about their family and their town. “He went up there like nothing was wrong, like there wasn’t this elephant in the room.”

At the mic, Dimora broke the ice with a Valentine’s Day joke. “Boy, do I feel good today,” he told the crowd. “My wife took good care of me this morning.”

Some women cringed. “For a second, everyone was like, ‘Did he just say that?’” recalls the Democrat. Then “the mood in the room changed instantly,” he remembers. “People laughed and stopped being on guard. I think it was one of the times Jimmy started to bridge the factions between black and white.”

Dimora had won over the group — and their endorsement for commissioner. In front of the whole crowd, Stokes embraced Dimora. “I cherish the relationship you and I have had,” Stokes said. The once-feuding party was coming together: Dimora wrapped them up in a big, happy bear hug.

Dimora beat Sweeney that spring thanks to his tenacious socializing. He was campaigning at four stops a night, shaking hands with everyone he could. Then he slaughtered a sacrificial Republican in the fall. The steelworker’s son and unfortunate sewage worker had become the most influential politician in Cuyahoga County, chairman of its dominant political party and one of three people controlling its government’s billion-dollar budget. He’d done it the same way he’d come to dominate Bedford Heights: He’d worked harder at building friendships than anyone else.

In Dimora’s early years as commissioner, people who needed his help often met him at the Holiday Inn Rockside for breakfast. Some mornings, the restaurant would be empty except for Dimora, his guest and his next few appointments, each sitting at a table nearby, patiently hoping to tap his influence. “We were like planes circling an airstrip, waiting to land,” a Democrat remembers.

Dimora ran air traffic control like an Italian grandmother. “Can I get you something?” he asked when a guest sat down. And like the best grandmas, he had an uncanny intuition.

“He generally knew what you were going to be there for before you went there,” the Democrat says. Dimora’s calculating political mind had already deduced what a guest’s constituents needed and how the county could help — a new project, a bridge or a social service. “He was very, very thorough in listening and talked very little,” the Democrat says. “When he responded, he’d always play out the angles first.”

Breakfast was for friendly business, evenings and weekends for the business of friendship.

“There isn’t a fundraiser I went to, Democratically, that he and [county auditor] Frank Russo did not show up at,” says prominent local campaign contributor Tony George. Dimora talked politics like a chef talks ingredients, peppering George with questions: “Why’d you back that? Why are you backing this one?”

Socializing gave Dimora valuable political information and fed his fierce social intelligence. “You underestimate Jimmy’s intellect at your own peril,” says fellow county commissioner Peter Lawson Jones. “He’s very perceptive. He reads people well.”

“He’s got a computer up there that never stops,” says former commissioner Tim McCormack. “If you’re sitting with Jimmy and you’re discussing a policy approach — who stands where, who stands to benefit, who stands to lose — you’re almost never going to get a fastball by him. He knows because he’s been out there, and he knows who the players are.”

You could nearly always predict two things about Dimora’s appearances: He was constantly late and constantly with county auditor Frank Russo.

“It was like a comedy routine,” says Jim Trakas, the former county Republican chair and former state legislator. “Jimmy’s picking on Frank, Frank’s willing to get picked on and picking back on Jimmy.” Dimora had a standard Russo joke. “Every time I see Frank I get gas,” Dimora cracked, playing off the auditor’s seals on gasoline pumps, which Russo adorns with his smiling face.

Trakas, a friendly rival of Dimora’s for a decade, noticed the strategic benefits of Dimora’s charm. “The guy never says no to any invitation, so people feel obligated to him because he’s willing to support their causes,” Trakas says. “And he calls in his chits. He’s very good at that.”

In 2002, for instance, Dimora called in every favor owed to him and nudged everyone nudge-able to help get Jones onto the county commission. Democratic Party regulars were deciding whether to award a midterm appointment to Jones, a Harvard-educated attorney, or county recorder Pat O’Malley. Dimora made calls, wrote letters and chatted up party members and influential union leaders, asking them to vote for Jones.

Dimora also lent Jones his regular-guy charisma. In front of crowds, he’d bounce a joke back and forth with Jones: They must be cousins, he’d say, since southern Italy and Northern Africa aren’t far apart. The jokes had a purpose: Dimora wanted to laugh off the party’s racial divide. It upset him that no black Democrat held a countywide office. “He would shame people,” a party member recalls. “Jimmy would say, ‘This community has been here for us forever, and to think that we’re not giving a qualified person a seat’ — he couldn’t understand it at all.”

Jones and Dimora didn’t just win; they ran up the score. Dimora gained an ally on the commission. And he proved that his brand of politics worked, that by paying attention to what people wanted — whether they hoped to move up in the party or just remain in his favor — he could get what he wanted, too.

The Democrats were nearly unbeatable with Dimora as chairman. The party has held every county office (except a few judgeships) since 1997. Changing demographics helped — Republicans were moving across the county line — but Dimora also made shrewd decisions about who should appear on the Democratic ticket.

“He’s kicked Republican rear ends from Euclid to Bay Village and the lake to Brecksville,” Trakas says. “He’s been tremendously effective.”

While friends and rivals rave about Dimora’s successes as Democratic chairman — a volunteer position — it’s harder for them to name accomplishments from his 11 years as county commissioner. Tim Hagan champions human services, Peter Lawson Jones pushes for economic development programs, but what’s Dimora known for?

“My sense is he’s not an ideologue,” says one observer. “He has no government philosophy.”

Actually, Dimora does have an approach to governing. “Jimmy Dimora is a builder,” McCormack says. “His instinct is to, where possible, build large and with impact.”

Dimora takes an interest in “the nuts and bolts of the county: who we buy rugs from, who we buy paint from,” says Adrian Maldonado, who was the county’s director of procurement and diversity until last year. “His constituents are people in the trades, people who build things.

“If Jimmy Dimora is invested in an issue, he wants to know all the details,” says Maldonado. “Did we do everything we needed to do? Does the aggrieved party have another shot at something else? The second bidder, is he clean?” Dimora or his aides might ask if a contract can be rebid, he says, or they might ask what the law says about the bidding process. “He never said to me, ‘Adrian, your job is on the line,’ ” Maldonado says. “He never asked me to do anything I might be ashamed of.”

Like a classic old-school Democrat, Dimora tries to jolt Northeast Ohio’s economy out of the doldrums with big government construction projects: the $425 million Medical Mart and convention center downtown, a $189 million juvenile justice center on Quincy Avenue.

“Large capital projects always excite Jimmy,” says Jones. “He perks up with those. Those mammoth projects fit with his mammoth personality.”

But Dimora’s appetite to build led the county into a mammoth boondoggle: buying the Ameritrust Tower in 2005. Dimora voted to demolish the skyscraper to make room for a new $160 million county headquarters — but after spending $40 million, the commissioners abandoned the project as unaffordable, leaving them with a vacant skyscraper they can’t sell.

Advisers had warned the commissioners about the project’s cost before they bought the tower. But Dimora didn’t want to say no to a big, ambitious plan to revitalize a barren corner of downtown. Cleveland needed help, and Dimora wanted to do something for it.

He reacts much the same way when friends and allies ask for help.

“I never thought Jimmy likes to say no to people,” Jones says. When the commissioners had bad news for someone, Dimora was uncomfortable delivering it. “The rest of us had to play the Grim Reaper.”

Dimora, Jones adds, “wants to be respected, certainly wants to be influential, but also likes to be liked. I always thought that was one of the reasons why he never liked to tell anybody no: ‘No, you can’t have this.’ I just hope that desire to be liked doesn’t prove to be his undoing.”

-the-party-was-nearly-unbeatable-with-him-as-chairman.jpg?sfvrsn=4945e18c_0)

Photo Caption: Jimmy Dimora’s emcee act cracked up crowds throughout Cuyahoga County. (He’s shown here hosting the local Democrats’ annual dinner.) The party was nearly unbeatable with him as chairman.

Delmonico’s Steakhouse looks like a scene out of the TV show Mad Men: an early-’60s Manhattan supper club with red leather booths, sultry mood lighting, trained sommeliers waiting on businessmen in suits. It’s four minutes from Jimmy Dimora’s house in Independence. He likes the biggest steak on the menu, the 26-ounce Cowboy steak, a ribeye. “I never leave there hungry,” he once told a reporter, “and when you fill me up, that’s an accomplishment.”

Dimora dined out regularly at pricey restaurants in Independence, Valley View and the Warehouse District: Lockkeepers, the Metropolitan Café, Osteria di Valerio & Al. He’d roll up with a posse that often included Frank Russo and J. Kevin Kelley, the former Parma school board president and county engineer’s employee who recently pleaded guilty to bribery.

They were “always having fun,” says Jim Trakas, the former Republican chair, who also lives in Independence and used to run into Dimora often at Delmonico’s. “They’re busting each others’ chops, they’re telling jokes about each other. You come over to say hi and they’re ripping on you: ‘Hey, make sure this guy doesn’t get fed!’ ” Sometimes, Trakas says, they’d be talking business, calling people on their cell phones, inviting them to come to the restaurant to talk something over.

When someone else picked up the check, Dimora noted it on a scrap of paper and stuffed it in his pocket, Trakas recalls. “I remember being at Delmonico’s one night, and he said, ‘Who’s buying who what? ’Cause I gotta keep track of this stuff.’ ”

Dimora’s annual disclosure forms are legendary in Cleveland political circles. He lists far more free meals and gifts than any other county official: an average of 56 gift-givers and 35 check-paying business meal companions a year, or at least 619 gifts and 389 meals since 1998 — from friends, real estate developers, county contractors, county employees. (Peter Lawson Jones reports six or seven gift-givers in a typical year and no free meals, and Tim Hagan usually lists one gift or none and no meals.)

Politicians have to list only people who buy them gifts totaling $75 or more or meals totaling $100 or more. But other politicians say Dimora reports every gift and free meal, no matter how small.

“I always thought that was highly ethical on his part, that he was scrupulous about reporting those things,” says Trakas. “He’s the guy in charge. Of course you would have people lining up to buy him breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

Bobby DiGeronimo, an executive with local contractor Independence Excavating, is listed on Dimora’s reports from 2001 through 2007 — not for meals, but for ballgames. The two men attend the same church, St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Independence. Dimora supports the DiGeronimo family charity, Cornerstone of Hope, a home for grieving families. Dimora and his family have watched Cavs and Indians games in DiGeronimo’s suites at The Q and Progressive Field. Those tickets are the gifts Dimora reported, says DiGeronimo.

“To this day, Jimmy has never asked me for anything except sports tickets,” DiGeronimo says.

In 2007, Precision Environmental, a DiGeronimo family company, benefited from a controversial contract decision. Precision had bid for a $7.4 million county contract to clean asbestos out of the Ameritrust Tower. A company from St. Louis had outbid it by $900,000, but county staff questioned the low bidder’s ability to perform the work.

As the commissioners’ vote neared, DiGeronimo’s brother Tony, who runs Precision, asked him if he wanted to call Dimora about the bid.

“No, I don’t want to do that,” DiGeronimo recalls telling his brother. “They have a decision to make. I don’t want to have to ask him to do that.”

That August, the commissioners voted 2-1 to award the contract to Precision. (Dimora and Hagan voted yes, Jones no.) Afterward, DiGeronimo says, he called Dimora and said he and his brother had debated whether to contact him before the vote. “Jimmy said, ‘Bobby, yeah, I’m glad you didn’t. I’m glad we were able to give you the job. It keeps money in the state.’ ”

DiGeronimo thought back on that conversation after the federal probe of Dimora became public. He wishes the FBI had heard them talking. “He could have said, ‘Hey, Bobby, how bad do you want this job?’ He never did that.”

Instead, court records suggest the FBI started listening to Dimora’s conversations a few months later.

On March 31, 2008, businessman Steve Pumper called Dimora and asked what he was doing, according to a prosecutors’ court filing.

“Oh, what the f—k, I’m doin’ nothing,” Dimora allegedly answered. “I’m trying to make calls, make a living, help my friends make more money than they already got.”

It’s the sort of quote a prosecutor might write on a dry-erase board and repeat in a trial’s closing argument: an elected official whose sense of duty has become twisted, who uses his influence to benefit his friends.

The federal bribery charges filed against Dimora’s friends, J. Kevin Kelley and Steve Pumper, never claim Dimora single-handedly rigged a bid or steered a contract. (The prosecutors’ court filings call Dimora “Public Official 1,” but he is easily identifiable from details about him. Dimora has not been charged with any crime.) The filings depict Dimora doing little favors: He puts in a good word for people, nudges, recommends, asks for a meeting to be moved up, calls the county staff to see if anything can be done for a buddy — and takes gifts from his friends before or after.

If the allegations in the Pumper charges are true, then Dimora’s purported comment to Pumper wasn’t just idle chat. In that same March 31 conversation, Dimora allegedly talked about having lunch at Delmonico’s the next day with the architect of the county’s new juvenile justice center. At lunch, prosecutors say, Dimora “promoted” the company Green-Source Products LLC to the architect. Pumper was a “de facto executive” of Green-Source, prosecutors say. (Green-Source is part-owned by relatives of Pumper, but an official speaking on the company’s behalf says Pumper was never an employee or owner.) The architect purportedly replied he’d make “an effort to use Green-Source products” in the new building.

Pumper pleaded guilty this July to nine crimes, including a charge that he bribed Dimora with $33,000 in cash and $60,000 in home improvements: a patio roof, a barbecue shelter and conversion of a shed into a bathhouse.

In exchange for the work and the cash, the court filing says, Dimora allegedly did at least eight official favors for Pumper, including help getting a country contract and loan extension for his company, DAS Construction. Dimora also allegedly inserted himself into two court cases involving Pumper, calling the head of a county agency to expedite Pumper's divorce case and talking to the judge hearing a lawsuit against DAS and the judge's staff to try to get a settlement.

In the feds' version of events, contained in the charges against Pumper, as soon as Dimora heart that the FBI contacted Pumper, he guessed correctly that the FBI was looking at Pumper's work on his house. The feds claim Dimora began paying Pumper back for the home improvements on May 23, 2008 — the very day the FBI confronted Pumper and asked him to cooperate with them. Pumper allegedly tipped Dimora off to the FIB visit through a mutual friend, and Dimora allegedly paid $600 to DAS that same day.

"Would you tell [Pumper} to please have his company send over the invoice on this?" Dimora asked a mutual friend on May 28, according to the Pumper charges. "I sent a check in, just so there is enough money on account towards the, uh, project."

"You know I paid for...the bigger addition," Dimora allegedly added. "I don't want to have nothing hanging out there that could come back to hurt him or me. ... I just want to cover all the bases so he don't have a problem and I don't have a problem."

Two day later, the charges say, Pumper sent Dimora an invoice for the work DAS had done at Dimora's house between 2004 and 2007, minus a $600 credit for the May 23 check. Dimora allegedly paid DAS $4,723 in the months afterward — which, if true, means Dimora would've still owed his friend's company $35,000. (Pumper resigned from DAS in April and is no longer CEO or part-owner, a company official says.)

Dimora has denied getting work done on his house without being charged. "No, I pay my bills," he said at his June press conference. "I'm telling you, it's allegations and lies, mistruths that were pained by people in trouble." Peter Lawson Jones says Dimora has told him "he paid for, or always intended to pay for, any improvements to his home."

Prosecutors also claimed Pumper gave Dimora $33,000 in cash between 2007 and 2008. "I can't get into those issues," Dimora replied when asked about it at a July press conference. "Maybe some day we'll have to refute that. But this is not the day that I can do it."

Dimora says he first realized the FBI was investigating him at the start of 2008.

"As early as 2008 — January, February — people around me, friends, were being asked to wear wires to try to entrap me," Dimora said at his June press conference.

Dimora's father, Antonio, died that January at age 75. Friends noticed Dimora was depressed over his loss, he says, and they suggested getting away to Las Vegas. So that April, Dimora, Frank Russo, Kelley and other friends flew to Vegas for a long weekend. (Russo, called "Public Official 2" in the court filings, is also easily identifiable from details. He has not been charged with any crime. His attorney, Roger Synenberg, says he "can't confirm or deny" whether Russo is PO2.)

"I paid for my trip," Dimora said this summer.

However, Kelley has pleaded guilty to two bribery charges involving Dimora, Russo and the Vegas trip. Prosecutors believe Kelley arranged for businesses seeking county contracts to pay for much of the vacation.

The feds say a business executive seeking county contracts worth tens of millions of dollars spent $4,500 on Dimora, Russo, Russo's traveling companion and Kelly in Las Vegas. He also allegedly gave Dimora casino chips of unknown value during the trip.

Details in the charges show that the bidding companies were Berea-based Blaze Building Corp. and Blaze Construction Inc. Prosecutors say Dimora and Russo nudged the county staff in a failed effort to help Blaze Building's bid for a $35 million construction job at the juvenile justice center, and that Dimora and Kelley arranged a consolation prize for the executive: his choice of a county inspector on a contract Blaze Construction had won to resurface part of Snow Road in Parma (a job it won by being the low bidder).

The feds also claim that Alternatives Agency, a halfway house that had lost its county contract and was trying to get it back, indirectly paid for Dimora and Russo's plane ticket.

In December 2007, Dimora and Russo allegedly talked to public employees, asking them to reexamine the common pleas court probation department's decision not to renew the halfway house's contract. In February, Kelley allegedly called Dimora from Delmonico's, where he was having lunch with Alternative Agency's then-executive director. By then, the halfway house contract had been revived, and the county commissioners were scheduled to vote to solicit bids for it the next day.

Kelley mentioned that to Dimora, who laughed. "I don't wanna know what you get out of this," Dimora allegedly said. "I don't even wanna f—ing know."

"I get nothing out of this," Kelley replied. (Kelley pleaded guilty this July to receiving$198,000 from Alternatives Agency in exchange for various favors.)

"I don't even wanna know," Dimora allegedly repeated. "The less I know the better."

"Definitely — the less you know the better is right," Kelley said. "Speaking of that, Vegas." Then, the charges say, they talked about their plans for the trip.

Just before they left for Vegas, the feds claim, Dimora wrote Kelley a $1,268 check for his first-class plane ticket — and Kelley handed Dimora cash from Alternative Agency to pay him back.

Dimora denies that. "I wrote a check. I paid for my trip. I never got a reimbursement," he said in July.

A week after Dimora's trip to Vegas, at a tense meeting on April 17, 2008, the county commissioners awarded the $250,000 halfway house contract to Alternatives Agency. (The halfway house, now renamed Cuyahoga Re-entry Agency, is under new management and is no longer under contract with the county.)

The contract was a minor agenda item that day. The drama came after Dimora, Hagan and Jones voted to sell the Ameritrust Tower to the K&D Group (the deal has since fallen through).

Dimora, feeling vindicated, lashed out at The Plain Dealer's critical coverage of the Ameritrust project and at two reporters who asked whether a Russo employee — former strip club manager and radio host Rosemary Vinci — also worked for him.

"I didn't go to college," Dimora yelled, "but I help people in this town! That's why I got to where I'm at. ... I help people. That's why they elect me to this position, and I'll continue to help people in this town!"

For someone under serious federal scrutiny, Dimora has said a lot about the allegations about him in the Kelley and Pumper charges.

"I am innocent," he said at this June press conference, "and I will refute that 51-page information of packs of lies, innuendos, mistruths by three people that are in trouble."

Dimora says Kelley, Pumper and others have lied about him, telling the feds what they want to hear in exchange for less prison time.

The incentive for Kelley, Pumper and others to cooperate with the prosecutors' case is huge: Kelley (who also pleaded guilty to taking bribes as Parma school board president from several contractors, including Pumper) could get his sentence reduced from about 11 to 14 years to roughly 6 to 7 years if the feds are satisfied with his testimony against others, a prosecutor said at his July arraignment.

Dimora has denied allegations that he improperly aided Pumper, including a suggestion that he helped get $1 million in county redevelopment loans for Green-Source's headquarters on Cleveland's East Side. Dimora said several officials approved the loans in a thorough vetting process.

"We're here about creating jobs," he said in July. "These loans are being paid, the jobs are being created. ... That's what our job is in county government, whether we have a relationship with individuals or whether we don't. We try to do it based on what's for the good of the community, the county and the taxpayer."

Dimora often makes arguments like this: Relationships between public officials and those with business before them are inevitable, and all an official can do is report the contributions and gifts.

Two years ago, when Rob Frost, the Republican chair, argued Dimora's many campaign contributions from contractors created "potential for political influence dealings," Dimora adamantly denied it.

"That's absolutely, unequivocally nonsense, ridiculous!" he told Cleveland Magazine in July 2007. "Those contracts are publicly bid. We award them based on the best numbers." Contractors "donate to everybody's campaign, including the Republican Party." He denied any connection between donations and contracts. "They're in town, you're an elected official, you have a fundraiser, they attend, they buy tickets!"

He made similar arguments this summer. "My colleagues have ... said I've never, ever approached them to steer a contract, or vote a different way, or do anything," Dimora told reporters at the June press conference. "If you look at our record, 97 to 98 percent of the time, we award it to the lowest bidder. Why would somebody have to help themselves if they're the lowest bidder?"

When Democrats gathered in Cleveland's Music Hall in May to appoint a new sheriff, Cleveland councilwoman Mamie Mitchell introduced Dimora with a flourish, and the crowd responded with a happy, rah-rah cheer.

With his voice reaching up to the stone comedy and tragedy masks above the blue stage curtains, he thanked everyone who had researched the legal qualifications to become sheriff. "It's different than being 400 pounds and breathing and alive to run for office," he cracked. "This actually has requirements to it!"

Though his self-deprecating comedy act seemed as winning as ever, much had changed. The Democrats chose Bob Reid, a Dimora ally from Bedford, as sheriff, but Lakewood Mayor Ed FitzGerald said Dimora had done little to help Reid.

"I haven't heard that he's said a word," FitzGerald said.

A Dimora endorsement, once a near guarantee of victory, is now tainted.

"He doesn't receive the invitations he previously did," says Jones. "Elected officials are turning back cheeks from him. Nobody's seeking his endorsement. Nobody's trying to get their picture taken with him on their campaign literature."

Since the FBI Raids, Dimora has turned anxious and wary, Jones says. If a door slams, he startles more than others. E-mails to his office now bounce to the county administrator. "He's not meeting with as many people," Jones says. "As far as he's concerned, some people he thought were friends of his have turned on him and lied about him."

Dimora's influence has waned. In July, he took a leave of absence from his volunteer position as county party chair. State Democratic chair Chris Redfern pushed him to resign, saying his effectiveness in the job had been "irreparably harmed."

Jones and Hagan have called on Dimora to recuse himself from all voting on the commission and to take a 60-day leave of absence from the job. Dimora has refused: "I've done nothing wrong," he said. Rep. Marcia Fudge says she tried to convince Dimora to resign as commissioner and party chair because "he clearly had become a major distraction to the party and, I think, the county government."

County treasurer Jim Rokakis agrees. "What he has done has crippled this government," he says. The Pumper charges — the alleged work on Dimora's home, the purported cash payments — turned Rokakis against his former ally.

"So Pumper did this for you because he liked you? That's OK?" says Rokakis. "It doesn't wash."

Rokakis says Dimora and Russo should resign: "Do us a favor and leave. Just go."

Dimora has shown no sign that he'll do so, even if he's indicted. His declarations of innocence suggest he's aiming for complete exoneration.

"I'm not resigning," he told reporters in June. "I want to continue on until the end of my term — Dec. 31, 2010 — and I intend to do that."

He might like to stay active in the party after that: "There may be some point where I want to consider [being] a full-time chairman when I get out of public life, as far as elected office."

Despite everything that's happened in the last two years, Jimmy Dimora is thinking of returning to lead local Democrats in 2011 or beyond. That's how certain he is that he's done nothing wrong.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5