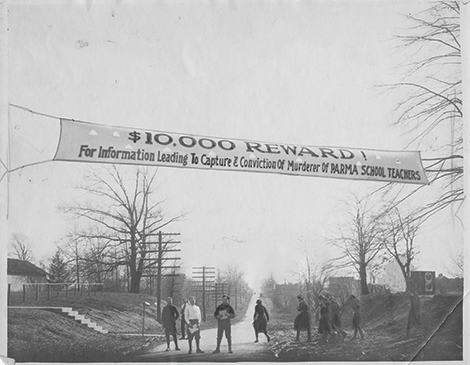

On March 11, 1921, students of Parma Rural High School assembled under a banner that screamed against a bleak winter’s heaven. The bucolic, sparsely populated township of roughly 1,000 had recently come under the nation’s magnifying glass.

On the morning of Feb. 17, students crunching through icy mud on the loneliest stretch of then-Bean Road had discovered the bodies of Louise Wolf and Mabel Foote strewn like discarded dolls. The women had been the children's teachers.

The pair were seen leaving the school together at 5 p.m., suggesting a swift altercation, as Foote’s broken watch froze on 5:15 p.m. The terrain, shredded mud for 600 feet uphill, and a dented umbrella, found among the teacher’s articles, revealed a vicious struggle on the victims’ behalf. The murder weapon was believed to be a fence rail.

By Feb. 19, hundreds of automobiles jostled from Cleveland to the crime scene. Spectators sloshed through ankle-deep mud for a glimpse or to hear stories from the students.

About 200 farmers banded together to comb the woods for the killer. Their manhunt likely trampled evidence for local police and Cleveland detectives.

There were leads. Pupils had overheard Foote speak of a stranger she’d met on the road a day before. A chicken coop north of the orchard was saturated with blood. A book in a barn five miles away had Foote’s name scrawled inside it, and in a letter, a “mental defect” claimed to be the killer.

Then-county prosecutor Edward Stanton said Parma would not rest until the murderer was apprehended. For more than 100 years, Parma has slept with one eye open.