John Glenn, his white shoes and magenta pinstriped seersucker suit collecting dust from a full day of open air political meetings, turns up the air conditioning in his 1973 Buick Limited and leans across the seat, an eye on the road, an eye on his passenger. “I love driving,” he confides. “I do some of my best thinking when I drive. I once read in the Reader’s Digest or someplace that the automobile is modern man’s Walden Pond. He can get away in the car to think, but he also must stay alert.”

It is only mid-summer but already John Glenn has done some of his best political thinking, crisscrossing Ohio in his hardtop, riding in Space Day parades as an ex-astronaut and Buckeye Road motorcades as a would-be United States Senator, talking with union leaders — in short, politicking as if Washington lay just beyond the borders of Cuyahoga County. Written off less than a year ago as some kind of political screwball, Glenn is now the de facto leader of the state Democratic ticket that should, barring any crisis, sweep Ohio this November.

Although he wouldn’t publicly declare himself a party leader, his behavior implies it and his aides acknowledge it. At a Democratic picnic in Lorain County, he hurried out of his car to shake the hand of the veteran county chairman before his wife could even get her door open. During a speech made over a crackling public address system from the back of a pick-up truck, Glenn shouted: “I want to see a big victory for all Democrats in this state this year.” At a labor meeting in a crowded Akron motel room the night before, he declared: “I want to help elect every Democrat in this room.”

If last year John Glenn was considered an out-of-work space hero looking for a job in Washington, that image has undergone a dramatic reversal. Not only has he matured politically, Glenn just may have found himself a place on the 1976 Presidential ticket. “Anyone who beats an old pol this year is being talked about as a man with a political future,” he says, “but that just goes to show you how bad things are nationally. No, I’m not thinking ahead to 1976, you guys are.”

Glenn can easily dismiss the idea of his being a counterbalance on, say, a Kennedy-Glenn ticket in 1976, but that is only for public consumption. Privately he has a sharp understanding of his political assets and is given to moments of analyzing his strengths, knowing he might be the one to lead an incumbent Democratic governor back into office this year. Governor John J. Gilligan, who also has national aspirations, doesn’t like to hear such things, but he has made his peace with Glenn for obvious political reasons.

Glenn will probably not emerge as a strong leader in the senate in the sense of a Mansfield or Jackson — he’s not that aggressive or shrewd — but he will have much more influence than his critics now predict. He has come of age at a moment when a clean political image will take a man far.

If he has any weakness still, it is with organizational Democrats and their brothers in big labor, who do not feel he has stood at their ideological side, that he is simply too conservative for a Democrat. Though Glenn often explained he had supported most legislation dear to labor, the leaders of the powerful unions looked to Senator Howard Metzenbaum in the primary because he left no doubt about being pro-labor on everything. At a cocktail party for labor leaders in the Park Centre this summer, Glenn left many of them shaking their heads when he announced that the issues of the general election would be “the same as in the primary” and did not once mention the word labor.

“Independence is his electoral strength,” insists Dennis Heffernan, Glenn’s Northeastern Ohio campaign coordinator before he resigned late this summer in an inneroffice power struggle. “He’s treading a thin line, but thus far he’s managed to balance all the elements and still make it in public life.” With his newly acquired but still shaky political agility, Glenn has finally earned himself a position of leadership. If he had gotten nowhere in the past by droning away on oblique issues, this spring in the primary he snatched a victory with unexpected cunning and ferocity. He quickly located Metzenbaum's jugular and struck.

Says Jim Schiller, Metzenbaum’s campaign manager this year: “I was surprised by the intensity of Glenn’s attack. I didn't think he had it in him.”

Still, Glenn does not yet have universal respect There are those, most notably the man who will be his senatorial opponent this fall, Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk, who are prepared to bloody him. “People tell me that if Glenn is elected, Ohio will lose a senator, and Massachusetts will gain a third,” Perk says.

“Glenn doesn’t have anything in common with guys making $7,000 to $12,000 a year,” says Perk’s campaign manager, Bob Bennett. “He hobnobs with millionaires; he is a millionaire! Besides, he made an awful lot of money in a very short time.”

Glenn's assets show him to be a millionaire, when you include his stock and property, but the charges could backfire as they did when Metzenbaum leveled them. John Glenn and Ralph Perk will never admit it publicly, but they have one common ability: both men have a talent for turning dangerous political attacks to their own advantage.

Glenn has made the best of both worlds, exploiting his image as a national historical figure as well as playing politics adroitly. His latest successes have not come entirely from the adulation reaped by being the first American to orbit the world. He won the Democratic nomination to the senate, certainly on his name and charm, but also because he politicked day and night, accepted the advice of professionals, sought campaigning funds on his own, and plotted strategy like any other man running for any other office.

Learning to play politics did not come easy. Before Glenn slipped in a motel bathtub in 1964 and injured his head just as he was beginning his first senate campaign, he never dreamed it would be anything but simple to make it in his new career. His name would be enough. Six years later, embarking on a second senate campaign, he still had the same delusions.

“In 1970,” says Glenn, sitting in his cantilevered den overlooking the spacious living room of his suburban Columbus home; "People saw me in the silver suit with the Big Eye in the forehead. I'd discuss history and other issues at a meeting, and the second question from the audience would be: 'Do astronauts drink Tang in space?' It would ruin the effectiveness of the meeting. But now those kind of questions don't come up as often."

Glenn believed the public automatically would nominate him in the 1970 primary because they had automatically made him a folk hero. He couldn't distinguish between the two worlds. (“The federal government spent a great amount of money to publicize the astronauts, you can't forget that,” snaps Mayor Perk.) So while Glenn was signing autographs in 1970, his opponent that year, Howard Metzenbaum, was signing checks for slick television advertising geared to create a bona fide candidate out of a little known big-city businessman.

This year, because of financial limitations and changes in strategy, the Metzenbaum people cut down on television, limiting their candidate's political commercials to vignettes about his warmth. “We knew Howard was viewed as ruthless and we were trying to overcome it,” allows one of his intimate campaign aides.

Glenn has had his own image — a nice guy but a lightweight — to overcome right from the moment he entered politics. When he left the space program in 1964 for what he figured was his rightful place in government, he did all the wrong things and alienated all the wrong people.

He challenged the aging Steve Young, then the incumbent Democratic senator, in the primary, with not so much as a discussion with a precinct committeeman. Although U.S. Rep. Wayne Hays of Flushing supported him, when the bathtub fall came and Glenn began suffering from dizzy spells and dropped out of the race, Hays was infuriated. To this day he has no use for Glenn. Hays made a remark that still persists today; something to the effect that Glenn cannot make a decision without his psychiatrist holding his hand. Metzenbaum whisperers tried to revive the comment this year, but didn't get anywhere. The remark distorts a relationship between close friends Glenn and Bob Voss, a stress psychologist for NASA, who acted as adviser in the abortive 1964 campaign.

Nevertheless, dropping out of a race for a politician, no matter the odds, is tantamount to a cop running from a stick-up man. Though he might have remained the people’s choice, Glenn, in 1964, was the politician’s pariah.

Once again capitalizing on his name, Glenn moved to New York, became vice president of Royal Crown, played the stock market and eventually bought into Holiday Inn franchises in Florida and Columbus (the Holiday Inn staff in Columbus recently hung a picture of a space-suited Glenn in the motel dining room against his protests. Yet, if Glenn outwardly plays down his association with the chain, he also uses it to his benefit. Glenn staffers staying in Columbus are given cutrate prices at the motel.)

From the outset, the 1970 primary, like the one six years earlier, was a disaster. The ticker-tape parades were still ringing in Glenn's ear. “When I went looking for campaign funds, people would say, ‘You’ll have no trouble beating Howard Metzenbaum, we'll wait for the general election.’ So, very few gave.”

“In 1970,” acknowledges Andrew Vitali, Glenn’s original campaign manager this year, “he was lunching with Rotarians and not with Democrats.”

“We didn't think we could lose,” adds his lawyer, Bill White, also the campaign treasurer then and now, “because the poll spread was so great it seemed insurmountable. But it was downhill all the way. Even Pat Cadell, our pollster, told us to be wary of signs of erosion. There was no way to see what Metzenbaum was spending, because there were no periodic disclosure regulations at the time. It wasn’t until the second week of April that we realized we were in a campaign. … We didn’t pay attention to Cadell when he said he was in town to help campaign and not to watch John sign autographs.”

White's tale demands further exploration:

“The field coordinator didn’t come on until late in the campaign, and he was doing things a boiler room volunteer should do. In two days, he drove across the state delivering campaign literature. Even the bumper stickers were too long to fit most cars — ‘Once and a While a Man Like John Glenn Comes Along.’

“On election night,” continues the well-scrubbed 33-year-old White, "we were still confident. The results came in showing us way ahead. At 3 a.m. we went from 10,000 votes up to 30,000 down. I was shocked. I called NBC to verify the results. We knew then that the black wards on Cleveland's East Side were pouring in l0-l for Metzenbaum and that Glenn had hardly campaigned there."

Actually, Glenn attended one black ward meeting that year in Cleveland that was so hostile to him that the ward leader offered to escort him to his car. This wasn't Columbus, much less his sweet little hometown of New Concord, and still seeing himself as the beloved hero, he couldn't understand what was happening.

Black politics still troubles Glenn — Metzenbaum beat him bloody in the black wards this spring — and in meetings this summer with Cleveland black politicians, he almost begged for advice on how to behave in such areas as East 55th and Central. What were the issues? he demanded to know. Ralph Perk may not be liked on the East Side, but he understands black politics as well as Carl Stokes does. Perk knows who the leaders are, what the issues of crime, police protection and housing mean and how to address a black rally in a church — who to flatter, who to avoid.

For the past four years, Glenn has analyzed his mistakes, concluding that if he was to become a successful politician he would have to do all the things politicians are required to do. He ran the Citizens Committee for Gilligan during the last general election, chaired the state Environmental Task Force and spoke at hundreds of Democratic functions across Ohio, all the while laying plans for a comeback in 1974. If you wanted John Glenn to dedicate your new municipal incinerator, he was available. “There wasn't anyone, except maybe the governor, who gave more speeches in Ohio in the last four years," Glenn laughs.

Still labor wanted Metzenbaum, and the party regulars, including Gilligan, urged Glenn to run for lieutenant governor, promising him a clean shot at the senate seat in 1976 or even the governor's mansion in ‘78.

“I didn't think what they were doing was right," Glenn says. "I felt I had earned my opportunity by my life in public service to run for the senate, rather than trying to make bucks. So I didn't want to be told what to do. I see myself as fulfilling a better role than lieutenant governor. … This was my time. If I didn't run for senator, I was going to do something else in public service — maybe go with a foundation — there was no problem in finding something worthwhile to do besides, I don't like deals."

At a state Democratic executive committee meeting in the fall Glenn accused the governor of “blackmail.” “I am alone,” he told the politicians, “and I mean alone, and I am a target now marked for political extinction because I will not go along in a deception of our Democratic voters."

The pols shrugged their shoulders, lighted their cigars and said goodbye to John Glenn. Two months later, the might and power of the party against him, Glenn entered the race for the senate. It seemed another useless exercise; his first attempts at campaigning seemed amateurish. On a statewide bus tour to publicize his candidacy, Glenn spoke to the Toledo chapter of Sigma Delta Chi, the journalism society, on ethics in politics. At the same time, his staff was snuggled in at an X-rated movie.

Though he was fumbling, Glenn was somehow chalking up enough yardage for a first down. No sooner had Metzenbaum filled the senate seat vacated by William Saxbe than his income tax problems were making front pages from Cleveland to Chillicothe. Screaming headlines revealed Metzenbaum had paid no taxes in 1969, though he had made a million dollars that year. Whether Glenn would have beaten Metzenbaum without Watergate and the tax issue is now an academic question. The significant point is that Glenn exploited the issue with a determination greater than Ralph Perk had in slamming James Carney as a Daddy Warbucks.

Glenn's campaign awoke with a start in March. He replaced his first campaign manager, Vitali, with Steve Kovacik, a streetrwise political campaigner with a taste for high living.

Certain members of Glenn's staff had rebelled against Vitali because they thought he was spending too much time in taverns, especially when he was needed. One evening Vitali had attended a private party in the main ballroom of the Sheraton-Cleveland Hotel when he was supposed to be with Glenn at the Cuyahoga County headquarters in the hotel basement. Glenn had to be restrained by Kovacik from dragging Vitali away from the party bodily. Vitali denies any wrongdoing on his part and contends he was set up by the Kovacik crowd. But in the waning days of the primary, he was made a traveling companion of Glenn and responsibility for directing the overall campaign placed in the hands of Kovacik.

Kovacik wasted little time. He soon had Glenn stomping Metzenbaum into the ground on the tax issue, forcing Metzenbaum to make public his 1040s, all the while reminding reporters that Glenn had already bared the details of his wealth.

Kovacik, who keeps an apartment in New York and a condominium on Lake Tahoe, put his Rolls Royce in mothballs and threw himself into the campaign in more ways than one. He and his second wife, the former Laurel Blossom Thomas, and her sister, Betsy Blossom, heiresses to the Blossom family fortune, kicked in $80,000 in contributions and loans to the Glenn cause, no small figure when one considers the primary campaign expenses were $600,000 and the debt, $200,000.

Kovacik had been itching to return to politics since he was ousted as director of field operations for John Gilligan in the 1970 gubernatorial primary. He had been destined to become Gilligan's executive assistant.

Mark Shields, the governor's strategist that year, and Jim Friedman, who later became Gilligan's executive assistant, engineered the purge because they felt Kovacik was overstepping his authority. Kovacik insists it was a personality clash, though there are intimations that Friedman and Shields opposed Kovacik's supposed free spending of campaign assets. “The irony of that,” says Kovacik, stroking his well-trimmed gray beard, “is that a post-election audit showed they owed me $9,000, which I personally had put into the campaign.”

Since joining the Glenn campaign, Kovacik has recruited his own staff, who, in all outward respects, are as loyal to him as to Glenn. He entertains the staff frequently in his penthouse in the swank Summit Chase apartments, where Glenn once lived, and often picks up the tab for their lunches and dinners.

"He's the godfather," says one campaign aide. "Unless you become part of his team, you're out in the cold."

Kovacik quickly moved to concentrate all power in his own hands and even warned the staff that only he and Glenn could make any statements to the press. “Steve made it clear he was in charge," says Vitali. "I got the feeling that they'd treated me tåe way Steve got treated by Gilligan."

Nevertheless, it is conceded that Kovacik changed the direction of the campaign and tightened up the loose organizational structure. “He demands loyalty," says another aide, "but he is responsible for making John into a complete politician. He made John take tough stands on oil, on Metzenbaum's taxes and on impeachment. And if John shed his wishy-washy image and came out of the primary as a respected candidate, it is solely because of Steve."

Kovacik, who may once again emerge as a strong figure in Ohio Democratic politics if Glenn wins, has a sensitive understanding of ethnic politicking — as president of the Institute of American Research in Columbus, he conducted voting surveys in l97l for a book on the subject. He urged Glenn to campaign in working class suburbs and even in Polish War Veteran halls. Glenn won all the white wards in Cleveland as well as the city's bluecollar suburbs, where 65,000 pieces of direct mail were unloaded a few days before the primary, the first time Glenn had ever used direct mail in any campaign! This ryas the labor vote Metzenbaum had counted on.

As Kovacik toughened up Glenn, Metzenbaum tried harder. Too hard. If some candidates can be said to have won their place in history with the slip of a tongue, such as George McGovern with his unforgettable "1,000 percent" support of his running mate, Thomas Eagleton, Metzenbaum carved his niche with a remark made at his $I00-a-plate fund raising party at the Sheraton-Cleveland in mid-April. He charged recklessly that "John Glenn never held a job.”

If there was a turning point in the campaign,” says Kovacik, "that was it."

As Metzenbaum was entertaining his supporters, Glenn was a few blocks away at the Flat Iron Café beneath the High Level Bridge at a 99-cent-a-plate corned beef dinner. The modest affair had been planned by Steve Avakian, an assistant and Marty Sammon, Glenn's Cuyahoga County manager, to provide a telling contrast to the big event downtown.

"When someone first asked me about Metzenbaum's remark, I didn't want to dignify it with a reply," says Glenn, "but I kept hearing it around, and when some pamphlets went into a plant in Toledo with the statement I became angry."

Glenn was considering how to react as he prepared for his upcoming City Club debate with Metzenbaum. One evening before the debate his staff formed a semi-circle around him in a Hollenden Hotel room and, as one man moderated with a stopwatch, Glenn was subjected to hundreds of questions of the sort Metzenbaum might possibly ask.

Glenn, who had purchased $700 worth of tickets for the debate in order to ensure a receptive audience, decided that night to challenge Metzenbaum on the “never held a job" slip. "I knew I was going to give it to him. I didn't care. I really felt he pulled a dirty one."

At a hiatus in the debate, Glenn stood up and said he wanted to reply to Metzenbaum's allegations. Pointing a finger at his opponent, Glenn reviewed his military career and declared: "It wasn't my checkbook, it was my life that was on the line. You go with me to a veteran's hospital, see their mangled bodies and tell them they didn't hold a job. Go with me and tell a Gold Star Mother her son didn't hold a job. Go to Arlington Cemetery, watch those flags, stand there and tell me those people didn't have a job. I tell you Howard Metzenbaum, you should be on your knees every day of your life thanking God that there were some men, some men who held a job!"

A crimson Metzenbaum replied feebly, but it didn't matter. Glenn had detonated a bomb. A black woman in the back of the audience began sobbing. The Glenn staff in Columbus heard a tape recording of the speech later that day. Most of them applauded, but Burt Schildhouse, a Glenn television adviser and veteran of many political campaigns, cried.

Though he was later accused by a friend of wrapping Glenn in the flag, Jim Dunn, who helped Glenn with the speech, was more than pleased. It had come off even better than he expected.

"He was willing to listen to advice," says Dunn, a former Metzenbaum adviser, now head of communications for lllinois Governor Daniel Walker. "I don't think there was anything I asked John to do [during the last two weeks of the primaryl that he wasn't willing to do. Before, he would have been reluctant to do something like the Gold Star Mother thing, but he also really felt it. I knew it would be effective."

Though the final speech had been his own, Glenn had heeded Dunn's advice and saved the punchline for the end.

Why a Gold Star Mother? "I've gone to several mothers to tell them their sons are not coming home," said Glenn. "Besides I wanted to be prepared with something in case he brought up the accusation again."

As Glenn was discussing his decision to use the speech, he stood up from his easy chair, paced his den, tamped his pipe and, raising his voice, allowed: "I don't like it when some dumb yahoo tries to run down the idea that someone risked their fanny for the country. I felt it gross and still do."

There are many other examples of Glenn's toughness, yet still as many which reveal he won't go all the way in playing ends-justify-the-means politics. Glenn sat toe-to-toe this summer with UAW leaders who had endorsed Metzenbaum in the primary and said it was their obligation to get behind him now that he was the Democratic nominee. On the other hand, when he was asked to ride in a Hungarian Parade on Buckeye Road in an Early Settlers Association float, he instructed an aide to determine whether Early Settlers Whiskey was the sponsor. "I once got caught riding on a commercial float and it looked as if I was endorsing the product, so I quickly jumped off and rode in a car," Glenn chuckles.

Though he has gotten better at it in recent weeks, Glenn has also had trouble personally soliciting campaign donations. During the primary, four aides cornered him in a Hollenden House room and urged him to telephone three or four wealthy potential donors. They argued that only he could wrench the money out of the businessmen. After an hour of pleading, Glenn finally agreed and began telephoning. Surprisingly, each of the prospects was unavailable, and Glenn left the same message with their secretaries: "Oh, just say John Glenn called." But as one of Glenn's aides passed by the telephone table, he noticed that Glenn, while talking, had kept his finger on the button.

After the 1970 senatorial primary loss to Metzenbaum, Glenn was typically philosophical about meeting his debts. He opened an account to pay his creditors, calling it the "Mark Twain Fund," because he believed Twain had authored a favorite remark of his about political spending: "In politics these days it even takes a lot of money to get beat with." Glenn intended to enclose a piece of stationery bearing the proverb with his checks, but someone with a more literary background informed him that Will Rogers, not Twain had made the oft-quoted comment. So Glenn opened a “Will Rogers Fund.” The stationery never was printed, and eventually the money was transferred to other funds; both the Twain and Rogers accounts were closed.

Since mid-summer this year, as campaign expenses have mounted, Glenn has swallowed his pride and made personal appeals for money to many of the same business and labor leaders who supported Metzenbaum in the primary. And several of them — Jim Carney, for one — who want to stay plugged-in in Democratic circles, are responding favorably.

In essence, Glenn has come to realize that certain facets of politics are distasteful, but they are part of the game. At 52, his once red hair turning gray and thinning almost to baldness, he is not about to ruin his future with an ignored telephone call — though it took him a decade to learn tlat relatively basic lesson.

As we walked down to the Scioto River, which curls behind his new $140,00 cathedral-ceiling home, Glenn talked about the raccoons that come up from the river seeking food. He has named one of them Kissinger because he's a peacelover but runs "when there's any trouble." Glenn is trying to keep his weight down, though since early this year he has dropped his daily mile run. A repairman, who calls his employer by his first name, is fixing a burglar alarm in the house that will buzz in a nearby police station if a window is so much as nudged.

These small details are the finishing touches on a painting. It is a portrait of a U.S. Senator: a man with a firm handshake and confident smile, a man who combines a folksy accessibility with the bearing of material and professional success, a man of government but not of politics. ...

But somehow it's all just a shade too genteel. The fact is John Glenn is a guy who has mastered the art of packaging himself. He is the dream of every Midwest county party chairman and New York marketing executive. Perk says it took a million government dollars to create the Glenn image, but he's only partly right. NASA and Walter Cronkite may have made Glenn a folk hero, but he took it from there and did his own trench work in politics. The hand of John Glenn is evident in the new portrait. The man in the picture may be a man above the hard-nosed game of politics, but the artist is a man who knows the path to the voter's heart.

In the end you can't help seeing Marty Sammon, Glenn's Cuyahoga County coordinator, a grin on his black-Irish face, standing in the Cleveland headquarters on primary election night pouring shots of bourbon for staff members and shouting: "Take McGovern and stick him, people still love the flag!"

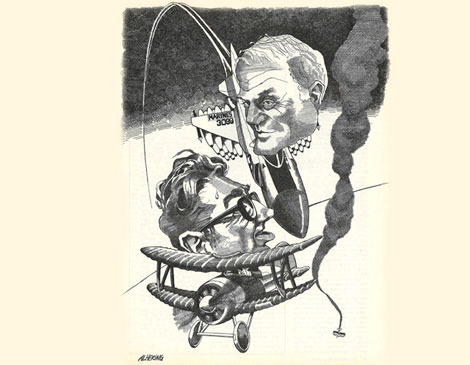

Look Out Folks, John Glenn Has Landed

After 10 long years, America's first space hero is on his way as a down-to-earth politician. First stop, the U.S. Senate.

the read

6:00 PM EST

December 9, 2016