It is almost, but not quite, a rule for life in this century that all new things are ominous. On the surface, when new things are invented, this may not seem to be so. But then, after a little while, it becomes so. Nuclear power is ominous. So is Master Charge. The jury is still out on instant potatoes. We await the verdict with some unease.

In mid-summer, Jimmy Carter appeared on television to prove he could be macho. The political experts had said that Carter’s political future was riding on his speech — that the nation had decided he was not capable of running a big government but was better suited to head a deacon’s committee for a new church roof.

We, as a nation, listened to Carter and wondered what we thought of him. The conventional way to find out would have been to wait for the following morning’s newspapers where the political pundits would tell us what we thought of him. But this was not a conventional night — not for Carter and not for national groupthink.

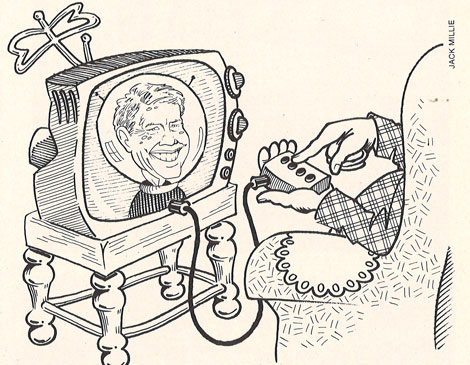

For down in Columbus, in 8,132 living rooms, people were listening to the Carter speech with strange gadgets in their laps. The gadgets looked a little bit like those remote control television tuning units that Archie Bunker always uses. They were little boxes with five buttons on them. The buttons were numbered one through five.

These families were subscribers to a Columbus cable television system called QUBE. QUBE brings its customers the normal assortment of first run movies and big deal football games that are the normal cable television fare. But QUBE is cable TV with a difference. The viewers can talk to it, respond to it.

QUBE put on the air, for instance, a show called Talent Search which is modeled after the Gong Show. The QUBE viewer gets to vote on the contestants with his button machine. His vote is registered instantly via computer. This is the ultimate in audience participation shows. And the night of the Carter speech it was to ascend to historic heights. NBC’s Jack Perkins journeyed to Columbus — an NBC hookup was completed. And seconds after the Carter speech, Perkins relayed to the nation how “Columbus” rated the president.

“QUBE viewers were asked five questions and told to answer by pressing a designated button on their consoles,” said Estelle Lehring, public relations director for QUBE. “This was explained to them before the speech and their response was tabulated instantly and broadcast to the nation.”

In this fashion we learned that 61 percent of QUBE viewers were optimistic because of the president’s speech, 18 percent were pessimistic, 21 percent were confused.

Forty-three percent were more confident in his ability to lead the nation, 33 percent were not, 24 percent were not sure. And on it went to the last question when the nation learned that 55 percent of the audience thought the country would pull together to solve its problems, 22 percent felt it would not and 19 percent were not sure.

Everybody connected with this electronic exploit seemed to think it was glorious. But the most I’ll give it is a not sure. I worry about this new QUBE tube dimension. I worry that it may fall into the category of new things that are ominous.

What bothers me is that the QUBE audience reaction was a reaction not so much to a speech as to a television show. For to the QUBE audience, the Carter speech was a television show the way Mork and Mindy is a television show. And we are a nation whimsical in our judgment of television shows.

The people responsible for commercial television have learned that the content of a show will often bear no relation to the ratings it gets. This is as true for news shows as it is for Mork shows. And so, television program directors are caught between the desire to be meaningful and the desire to get good ratings.

In politics, the ratings book is supposed to be published on election day. Once every four years, the people rate the president. Occasionally, newspapers publish the results of polls which reveal that a president is slipping in the ratings. But such polls can be misleading — can be downright wrong as the polls were with Harry Truman before the 1948 election.

Suppose, though, that an overwhelming number of people were hooked up to a QUBE system and could instantly rate a presidential performance. It would seem to me that then a president would be in the same dilemma as the program director.

He would be forced to make a choice between content and ratings. Ratings which would receive instant national publicity. Which would he choose?

I’m afraid he would go after ratings. I am afraid he would become a television “personality.” I am afraid the criteria for his selection would be the same as the criteria for the selection of a news anchorman in a major market. I am afraid that very soon we would judge our presidents almost solely not on what they do but how they play. I’m afraid we are doing that already and I’m afraid that nobody seems very afraid of that.

But then again, I scare easier each year.

This story originally appeared in Cleveland Magazine's September 1979 issue.