On February 17, 51 days remain until the total solar eclipse. Jay Ryan’s sure of that number. He keeps a daily tally — and if he’s not sure, he double checks the countdown on his eclipse website.

The fluorescent lights in the basement of Mac’s Backs Books on Coventry glint off his glasses as he talks to a dozen attendees about his favorite topic. This is one of a handful of appearances Ryan has on his calendar leading up to the eclipse in early April. Behind him, a small screen shares a presentation titled “Eclipse Over Cleveland,” subtitled: “Have You Heard? Why the 2024 Eclipse is a really big deal and why you should get excited!”

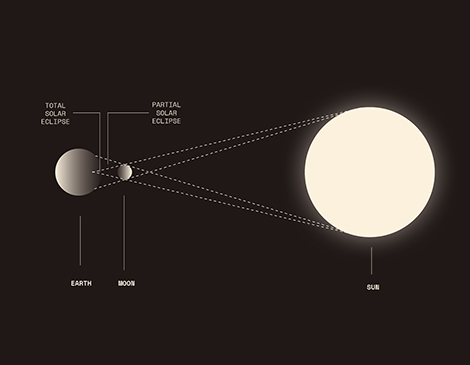

Here’s the really big deal: On April 8, the cosmic phenomenon will traverse North America, the result of sun and moon aligning in orbit. It will plunge Downtown Cleveland into three minutes and 49 seconds of darkness, a 360-degree sunset — an otherworldly sight in the middle of the day.

Predictions project many Northeast Ohioans, plus about 200,000 visitors, swarming the area on that spring Monday, eyes to the sky, witnessing an astronomical occurrence that spans just two and a half hours, including both totality and partial eclipse phases.

A month ahead of time, Cleveland is already in an eclipse frenzy.

Businesses are creating limited-edition merchandise; organizations are planning large-scale events; and a slew of Northeast Ohio school systems including Cleveland Metropolitan School District and Akron Public Schools have canceled classes for the day. City planners, emergency management departments and eclipse focus groups are scrambling to keep up.

Ryan, a 62-year-old self-taught astronomer, is in the center of the bustle, trying to share his excitement. A handful of the most enthused Clevelanders are here in the Cleveland Heights bookstore, too. Melted slush puddles beneath attendees’ chairs. Ryan’s wife, Debbie, knits in the back row.

Ahead of the talk, Ryan sips a cup of black coffee at Phoenix Coffee Co., just down the street. A flurry of snow whites out the scene beyond the windows.

Peeking out of a black suit jacket is one of his “Eclipse Over Cleveland” T-shirts: a cheesy commemorative design featuring the city skyline, a glowing eclipsed sun and red-and-yellow font, which matches the 33,000 pairs of solar glasses he bought and sold for $2 a pop in the past year. Only 4,000 remain. He expects them to be gone by the end of February.

RELATED: Cleveland's 2024 Total Solar Eclipse, By The Numbers

It’s not really about making money for Ryan. It’s about giving Clevelanders, especially the kids growing up within city limits, like he did, a chance to look at the sky and find inspiration in the stars.

“I can say that most people have no idea what this is, and therefore they’re not interested. They don’t understand that this is a rare thing; that this is the only total solar eclipse we will have over Cleveland, Ohio, over a” — here, he enunciates each number, carefully — “Six hundred thirty-eight year period. From 1806 to 2444. This is it —”

He speaks with a tinge of annoyance, like he’s explained this many times before to people who couldn’t grasp the significance of the event he’s been specifically planning for since 1994 — the event that’s far rarer than the partial eclipse that first sparked his interest in astronomy when he was an 8-year-old Cleveland kid — that pivotal moment for him, long before he met his wife at a Cleveland State University bible study, before his children and grandchildren, before his hair grayed and receded — before years, decades, spent dabbling in astronomy through his Starman comic strip and freelancing and telescope-building and with, always, unquenchable enthusiasm — and which brings us to this day, where he reminds us, again, of the countdown:

“— and it’s happening in 51 days, in our lifetime.”

A Big Day

In late February, Cleveland marketing pros, event planners and organizational leaders convene at the CanalWay Center in Cuyahoga Heights. The Eclipse Planning Committee, assembled by Destination Cleveland, reviews its latest push: an image of a basketball eclipsing the sun, with a tagline, “The Land of Going All Out.” They sip on cups of coffee and munch on eclipse-themed cookies from Luna Bakery.

Ryan is seated at a table, next to one of his neighbors, city councilman Kris Harsh of Ward 13. “Forty days!” Ryan eagerly announces to the room, resuming his ever-steady eclipse countdown.

The group discusses topics like eclipse glasses, city PR, event management and expected traffic. These have been ironed out as much as possible, a month and a half early.

Emily Lauer, Destination Cleveland’s vice president of PR and communications, helped stitch together these plans, coordinating with organizations and departments inside and outside of Cleveland. They worked with Nashville’s tourism department to glean advice and experience from the 2017 total eclipse that occurred there.

“It’s hard to believe it’s been seven years since some of the first conversations — but a couple of years ago, we decided that our best role in this was to be a convener of the organizations around town that would likely be planning events,” Lauer says. “We formed a local organizing committee. That group has been really actively collaborating to ensure that the visitors to Cleveland have a world-class experience and also so that our residents have an amazing experience.”

The solar eclipse isn’t the only major event happening on April 8 in Cleveland, after all.

A few other highlights: The Cleveland International Film Festival (April 3-13), the NCAA Women’s Final Four Championship the weekend before at the Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse (April 5 and 7) and the Cleveland Guardians’ home opener (April 8).

Those events will draw in thousands of Clevelanders to various corners of the city, so the week will be busy even without considering the eclipse chasers and astronomy fans who travel the world for a unique view of the phenomenon.

“I guess if I were king for a day, it would be nice to be able to spread things out more evenly,” says Ed Eckart Jr., the senior vice president of operations of Downtown Cleveland (previously Downtown Cleveland Alliance), “but that’s not even remotely possible.”

As the former assistant public safety director of the City of Cleveland, Eckart has helped manage some big events before. He oversaw the Republican National Convention in 2016 and witnessed the city’s population balloon during 2016’s Cavs championship parade, which he predicts to be a pretty good comparison to Eclipse Day.

The parade brought roughly one million people to the city’s center for one wild, claustrophobic, wine-and-gold-confetti-filled day. Take away the confetti, and April 8 might also be wild and claustrophobic in certain areas with Clevelanders flocking to parks and parties to view the natural phenomenon.

Two of the city’s major events are slated at the Great Lakes Science Center and its surrounding streets (which will be shut down to traffic), and at Wade Oval in University Circle. Other parking bans, similar to what the city experiences on Browns game days, might exacerbate gridlock and traffic issues, especially in the busiest parts of Downtown, says Eckart.

Eckart will not be at any of the parties. He’ll station himself in an operation center from which he’ll monitor crowds and safety situations. “Wherever I’m at, I’ll step out right before totality and watch it happen, and then go back to work,” he says.

Thirty miles west, Dave Freeman plans to be managing Lorain County’s Emergency Management Agency as its director, responding to an expected visitor influx as the county has branded itself the center of the eclipse.

The eclipse’s path of totality touches Lorain County like a spotlight (well, the opposite of a spotlight), and the county is capitalizing on the coincidence.

With three minutes and 53 seconds of darkness — that’s four more seconds than Cleveland — ads showcase the county’s lengthy totality on billboards throughout its neighboring counties: “Lorain County is your front row seat for the solar eclipse,” the digital message reads in bold letters, accompanied by a countdown showing the days, hours and minutes remaining until the big moment.

Those four extra seconds might draw more visitors than elsewhere — even more than county fairs, which have interrupted cellular service in the past, Freeman says.

And unlike the city of Cleveland, Lorain County and other suburbs’ roadways lack the extra lanes that can accommodate thousands of visitors.

The determining factor on exactly how many visitors? Well, that’s out of anybody’s control.

“I’m kind of hoping we’re gonna have horrible weather. It’s a little selfish,” Freeman says, a little facetiously, with a laugh. “Sitting in my seat, it’s a little bit different view of this whole thing. I would much prefer it move a couple hundred miles to the east or something. I’d be fine with that. But it’s a huge deal for us.”

In the meantime, Freeman and his team are conducting practice runs, imagining emergency scenarios and responses in the weeks leading up to the event. They’ve been chatting with Verizon to add an auxiliary cell phone tower in Avon Lake. They’ve identified temporary stations for ambulances, police cars and firetrucks that could otherwise be stuck in traffic on the big day. And they’ve coordinated with most agencies and organizations in Lorain County — the entirety of which will be swallowed by totality on April 8.

Experts advise Northeast Ohioans and visitors to have a full tank of gas in their cars and to get extra food, in case traffic backs up roadways, grocery stores and restaurants — but Freeman notes these are common-sense, typical precautions for any circumstance, not unique to Eclipse Day.

If you choose to brave the traffic and crowds, Northeast Ohio is as ready as it can be.

Many organizations have been busy preparing for this day since 2017, when the city experienced a partial solar eclipse: the edge of a total solar eclipse that tracked other parts of North America.

Just one more Eclipse Planning Committee meeting is slated for late March, before the big day.

At February’s meetup, the group inside CanalWay Center breezes through a slideshow of all the ways it will “activate” the city on April 8.

“Activate.” It’s a word you hear a lot from marketing teams. As though the city’s dormant for now. As though it’s waiting for its moment to come alive.

Maximum View

Three astronomers stand in the dimly lit planetarium inside the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. They’re attempting to describe what to expect on April 8, but in this room, it’s probably easier to just see it.

“Right now the sun is very active, and so the corona is going to be much, much brighter, much more symmetrical,” astronomer Monica Marshall says. Her work badge hangs on a lanyard around her neck; she got it about two years ago when she was hired on at the museum, years after a high school internship that both she and fellow CMNH astronomer Destiny Thomas completed. She clicks the computer mouse a few times. “It looks more like a diamond rather than, I don’t know — if I could show you real quick …”

The room’s scene changes. We look up at the dome. Two browser images appear, corners pulled and distorted on the half-sphere overhead.

“The one that’s to the left, that was during the solar minimum,” Marshall says. “In 2017, the total solar eclipse across the United States, the sun wasn’t as active. This time it is.”

The wispy strands of sunlight are brighter, bolder in the image on the right. Small red flames bump out around the circumference of the circle. Solar prominences, Marshall says — storms on the sun’s atmosphere layers: the photosphere, chromosphere and corona. Clevelanders may see those, too, on April 8.

RELATED: What to Expect at the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse in Cleveland

It’s momentous: The last time Cleveland experienced a total eclipse was on June 16, 1806 — roughly a decade after Moses Cleaveland founded the City of Cleveland. Local indigenous populations and just a handful of settlers experienced the event unfold.

“On the 16th of June a total eclipse of the sun occurred, which for a short time, produced in the shady forest the darkness of night,” reads an 1867 account, The Early History of Cleveland, Ohio, written by Charles Whittlesey.

“There are a couple records saying that the native tribes that were living in this area, they were affected by the eclipse, thinking that their great spirit was offended,” Marshall says. “When the eclipse happened in 1806, it was looked at as an omen, ‘How dare you sell your land to the settlers?’”

The darkness of totality fell before Cleveland was developed into much of a city. No skyline or roads. No crowds of people wearing protective glasses.

“It was probably a lot of forest,” Marshall says.

Fellow CMNH astronomer Nick Anderson shrugs. “Less light pollution.”

While both Marshall and Thomas are experiencing the lead-up to their first total solar eclipse on April 8, Anderson’s been through this before. He’ll dip into the darkness of totality for a second time; his first was when he traveled to Franklin, Kentucky, in 2017, shortly after starting his job at CMNH.

“Memorable is an understatement,” Anderson says. “It’s really surreal.”

And, notably, it was worth the 15-hour drive (normally five hours) to get home.

“The minute you see your first total eclipse of the sun — the minute it’s over, you’re eagerly awaiting the next one,” he says.

This time around, he’ll be stationed on Wade Oval for the museum’s “Total on the Oval” event, counting down the minutes and seconds to the eclipse alongside Thomas and Marshall. When it’s time to take off their eclipse glasses and gaze at totality, Anderson plans to be with his family, including his nearly 1-year-old daughter, to watch her experience the once-in-a-lifetime event in her own way.

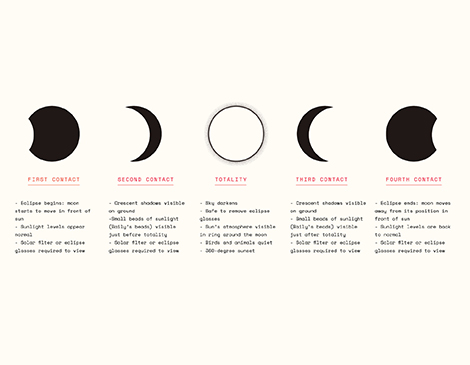

Here in the planetarium, Marshall clicks the computer mouse again. The room’s curved ceiling brightens into a scene of a sky with the sun shining overhead. The moon creeps in, and starts to cover it — the phases of a partial eclipse, moving toward totality, right in front of us.

“We’ve got to do our safety plug,” Anderson says methodically. Marshall and Thomas laugh. (They share these details often, with reporters and museum visitors alike.) “The key thing to remember is that only during totality, during those nearly four minutes, is it safe to look up toward the sun just with your eyes. Prior to that, and after totality, you’ll need eye protection.”

The image transforms as the moon blots out the sun, creating a deep sunset, darkening the room. The diamond ring of light is tangible in the museum.

It lasts just a few seconds. Marshall taps the mouse again. The moon phases back out, and a blast of light returns the scene to an artificially sunny day.

Astronomical Advantage

In a different part of town, another scientific institution ramps up for another weekend-long party around the same time as CMNH. The Great Lakes Science Center’s multi-day bonanza brings together institutions like the Cleveland Orchestra, Cleveland International Film Festival, NASA and Columbus’ Center of Science and Industry for a collision of arts and science. It’s all going down outside of GLSC, the Cleveland Browns Stadium and the field near the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. (The Rock Hall is hosting its own weekend celebration, featuring a DJ set from Grandmaster Flash on Saturday.)

“There are a lot of reasons we are taking such a major role in hosting this event on the shore of Lake Erie,” says GLSC President and CEO Kirsten Ellenbogen, “and a lot of it has to do with geography.”

RELATED: Total Solar Eclipse Cleveland Party Guide: Where to Be in Northeast Ohio on April 8

Specifically: Lake Erie. Lake breezes help with cloud conditions even in weather-turbulent El Niño years. The National Weather Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predict cloud cover swathing much of Ohio — except for a thin strip of land on the lake’s edge.

“Right Downtown, right on the shore of Lake Erie, NOAA is predicting it will have better viewability than even Dallas, when you’re on the lakefront. That changes once you get away from the lake,” Ellenbogen says. “We’re truly well-positioned to be the gathering place for people who want not only a great experience viewing it, but a great experience coming together with terrific science and arts organizations from around the region.”

Out-of-towners are flocking in and booking up short-term rentals in the area. According to Destination Cleveland, hotels are filling up. Airbnb released a report in late February stating that Cleveland is one of the most popular cities on the eclipse’s path of totality, behind Austin, Indianapolis, Montreal and Mazatlán, Mexico.

Local businesses are well-positioned to reap advantages from the event. T-shirt companies like Cleveland Clothing Co. and GV Art + Design released lines of eclipse apparel. Anne Cate, a local designer brand, created an eclipsified version of its popular Cleveland skyline handbags. Akron’s EarthQuaker Devices even put out a limited edition eclipse-themed guitar pedal.

RELATED: How to Gear Up for the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse in Cleveland

Market Garden Brewery owner Sam McNulty brewed a fresh batch of his “Totality” IPA beer following the success of the 6% ABV drink’s first run about six months ago, which, he says, “sold like hotcakes.” Cans and drafts of the creation are for sale at Market Garden’s Ohio City Brewpub and also at Heinen’s.

“It was basically just a way to spread the word,” McNulty says. “We were shocked at how many people in Cleveland didn’t know we were, like, smack dab in the middle of totality.”

Treasured Memory

In Lorain County, NASA Glenn Research Center scientists Nancy and Steve Hall plan to gather with family and friends on their property to experience a total solar eclipse for a second time in their lifetimes, and they expect it to look quite different from the first. They’re hauling their Celestron 8 telescope, their Coronado solar telescope and their solar binoculars out to the yard, bringing the 223,392-mile-away sight of the moon passing the sun just a little bit closer. They’ll make sure their fire pit is well stocked with firewood. And then they’ll pray for good weather.

“We’re just ecstatic about the fact that we’re going to be able to actually see it, in our lives, when it’s rare,” says Nancy, a self-proclaimed “space enthusiast.” A virtual background of futuristic spaceships and galactic imagery outlines her silhouette in a video call. “I mean, it happens all the time here on Earth, but because the Earth is mainly water, you don’t get to see that as much.”

Back in 2017, after driving their daughter to college at Bowling Green State University, Steve and Nancy went on a road trip to see the total solar eclipse in Cameron, Missouri. But when a weather forecast showed a high probability of clouds, the couple made the last-minute decision to drive more than 550 miles to Franklin, Kentucky, instead.

They set up at a city park at 7 a.m. on Aug. 21, lugging their telescopes and binoculars to view the partial phases of the eclipse, sharing the sights with other visitors. Nancy nixed the idea of photographing the eclipse, even though she’s done some professional photography in the past.

“That year we wanted to really enjoy it, because we knew NASA, everyone, would be taking pictures,” she says, “so we spent that day just sitting and watching it.”

After the partial phases, they reached two-and-a-half minutes’ worth of totality. An eerie darkness settled over the park; the birds stopped chirping. And then, just as quickly as it all started, the sun emerged again, flipping nature’s light switch back on.

Later, they drove home. The trip totaled 2,196 miles, and five states, in the course of six days, says Nancy.

“It’s just one of those cool things in science that doesn’t happen all the time. But then when you see it, it makes you marvel,” she says. “We’re just lucky enough to be in a position where we get to see it.”

RELATED: The Total Solar Eclipse will Bring a Magical Shared Experience to Cleveland: Essay

And we get to see it in our backyards. For CMNH’s Destiny Thomas and Monica Marshall, the event holds significance, looping back to their high school internships that sparked their then-future careers as astronomers.

“It’s kind of full circle to be in the place where you hold that passion for astronomy, and you get the chance to see this kind of coincidence we won’t get to see for hundreds of years from now,” Thomas says. “Once it starts, I’m just going to pause, and be present, just enjoy those almost four minutes, make them as long as possible.”

“Special” is a word Jay Ryan also uses to describe it. He went on a trip to Hartsville, Tennessee, with family and friends to view the 2017 eclipse.

It was a full-circle moment for the former kid who begged his mom to travel to South Carolina to see the total eclipse in March 1970 and instead had to resign himself to standing outside in his Old Brooklyn yard, catching the edge of it — a partial eclipse. But when he couldn’t figure out how to get his pinhole camera to work, he ended up missing the whole thing.

He remembers that day vividly. He remembers the frustration.

And he remembers turning on the Channel 5 news that night, where he heard about his next chance to witness a solar eclipse.

“The host said, ‘If you missed today’s eclipse, you’ll have another chance in the year 2017.’ It’s 1970, I’m 8 years old, the Kent State shootings happened two months later, Apollo 13 happened a month earlier,” Jay says. “So I’m an 8-year-old kid contemplating when I will be 56.”

He pauses. The numbers crunch in his head. He thinks of a different day, the one in Hartsville six and a half years ago: finally, his first total solar eclipse.

“You know, the funny thing about arithmetic, it’s like a miracle or something,” he says. “In the fullness of time, it’s 2017. I’m 56 years old, and I’m looking at the total eclipse of the sun from Tennessee. How about that?”

Jay Ryan is a man of many countdowns. He knows exactly how many days it will be until the 2024 solar eclipse, and he’ll tell you the moment you start talking about the event. He keeps track of these things, these important dates and highlights of life.

And he’s looking ahead past all of that, for a moment at least, to the next time a total solar eclipse will even touch Ohio again, in 2099, in Columbus.

Just like when he was 8 years old, he thinks of the faraway date and, this time, he thinks of his family, his grandsons — “they will be 79 and 77, respectively; they’re toddlers right now; they’re babies” — these branches of his life extending into the future of it all.

It’s significant.

Once in a lifetime.

“It’s so uncommon, so infrequent, that people just don’t understand yet,” Ryan says.

On April 8, Clevelanders will.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.