Meet Carl Baldassarre, The Banker-Turned-Rockstar

by Mark Oprea | Jun. 28, 2022 | 12:00 PM

Howard Tucker, Mort Tucker Photography Inc., John C. Benson

The 2014 PNC Bank portrait of Carl Baldassarre can only be described with one word: corporate. There’s that pressed, burgundy plaid suit jacket. That executive taunt of folded arms and trained smile. The gelled hair swooped into a silvery wave. This is 35-years-in-finance Carl, 37-years-married Carl. This is six-figures, shake-hands-with-Ivy-League-boss Carl.

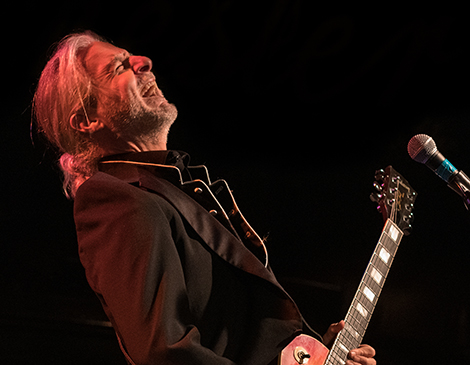

But just five years later, a seemingly different person emerges. The hair is now loose, a tied-up ponytail. The body is slim, about 70 pounds lighter. The cheeks are covered in the beard of an Italian artiste. John Lennon specs hang casually above a childlike beam, not one of financial posturing.

Both men are Carl Baldassarre, a 62-year-old rock and classical musician who helped grow one of the biggest private equity firms in the Midwest. Ever since retiring at 56 from corporate America, Baldassarre, a Cleveland native, has metamorphosed into a full-time itinerant guitarist and composer, recording seven albums of tracks in a multiplicity of genres, everywhere, he says, from “Burt Bacharach to Bach,” from fugue-inspired progressive metal to pop-leaning Nashville country.

“A Grammy-award winning producer once described my music,” Baldassarre says, “as ‘somewhere between Christmas and being burned alive.’”

But it’s only now, in 2022, that Baldassarre is making his debut official.

Following three years of production, he just released Grand Boulevard this spring, a strings-laden rock-and-orchestral album of personal retrospectives. And, due to the explosion surrounding his Led Zeppelin Revival shows, Baldassarre is planning what may be his most singular project yet: a collaboration with Tower of Power singer Marcus Scott on a neo-throwback show called “The Soul of Zeppelin,” which will make its way to the Music Box Supper Club in the Flats on July 2.

Before he helped build a $3 billion private equity firm, Baldassarre was a gaunt, music-obsessed teenager growing up in Euclid. His parents, Baldassarre is wont to say, were influences of a double-edged variety. His mother, a high school English teacher, was an avid short-story writer who battled a lifelong addiction to prescription pills. His father, a hustling master of odd jobs, found an escape from his own demons in bars.

"We just kept moving because we had to stay one step ahead of the creditors,” Baldassarre says. “I think I moved, like, six times before I was 12.”

Baldassarre distracted himself with a $15 Kay guitar, rigging it with a microphone to imitate a real acoustic-electric guitar. The soundtrack of the ’60s — especially the Beatles — became a realm of intrigue and escape.

In 1970, a year after Woodstock, Baldassare’s oldest sister, Lynn, walked into 11-year-old Baldassarre’s bedroom with the Led Zeppelin II album, a 1969 showcase of Jimmy Page’s guitar wizardry. "She dropped the needle on 'Heartbreaker,’ ” he recalls, “and I just completely freaked out.”

Seven years later, Baldassarre began studying classical music and formed a band, Abraxas. Those memories, however, are mired in tragedy. His mother was at home in the kitchen when, as Baldassarre recalls, she suffered a relapse in the late afternoon and overdosed. “I came home from school and found her dead,” he says. “And that’s when I got my electric guitar.”

Mark Hughes, a childhood friend and, later, roadie for Baldassarre’s progressive rock group, Syzygy, recalls a light bulb moment soon after the death. "I remember him playing that Heartbreaker solo right in front of me,” Hughes says. “And I thought, Holy crap, this guy is something else.”

Yet, instead of mimicking Page’s life, Baldassarre veered elsewhere. Determined to flee as far as possible from poverty and addiction, he dove head-first into the world of finance. In 1979, he was hired as a bank teller for National City Bank, which became PNC Erieview Capital in 2008. There, he began decades of ladder-climbing. In 1989, Baldassarre was offered an over-the-edge job: handling a $25 million portfolio of private equity. Knowing the seat would further concrete him into the finance world, Baldassarre hesitated. "I didn’t know if I was that guy,” he says. He turned down the job. A day later, after a pep talk from a co-worker, "I took it.”

Decades passed behind a facade of perfection. By the mid-’90s, Baldassarre was busy raising two boys and built a 6,500-square-foot home in Kirtland. His music was there, per se, but it was often rushed and stifled, always kept in-check by the economic draw of private equity investing.

At PNC, Baldassarre would grind with his colleagues to wrangle in some 230 companies — all while covertly moonlighting as a guitarist for Syzygy, which earned occasional plaudits overseas. (In 2014, a German music blog dubbed Syzygy "The Best Prog Rock Band You’ve Never Heard.”)

"I thought he was a sort of hobbyist," Eric Morgan, a managing director at PNC since 2000, says. “I had no idea the level of enthusiasm he put into it.”

Baldassarre was approaching 55 when he finally lost his grip.

In 2014, he and his wife separated, and Baldassarre moved into their lakehouse in Madison. He pulled back from his job, converting to a consulting position. He dieted, cut out sugar and dropped to 150 pounds. He brought out old suede coats, grew his hair and adorned his ears and fingers with jewelry.

“I was returning to the person you saw when I was a kid,” Baldassarre says. “I was leaving all the things that were poisonous to me. I was dying emotionally, physically, spiritually, humanly — in every way you could imagine.

“And then, one day, I was completely reborn.”

He began composing avidly, writing 72 pieces of music in three years. He toured Italy and Germany, once leaping over a velvet rope in Vienna to test arpeggios at the piano where Beethoven composed his Fifth Symphony. “I was escorted out,” he says, laughing. He spent $2,600 a day recording at London’s Abbey Road Studios with a 30-piece orchestra.

Before the pandemic derailed his debut, he was recording Collinwood Yards, his sophomore pop album, at Sweetwater Studios in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Marcus Scott was there, too, recording vocals for his own musical retrospective, Back 2 Da Soul, in a neighboring studio space.

The two met and liked each other. A lunchtime discussion bore a new idea: marrying Baldassarre’s Page mechanics with Scott’s buttery croon. The Soul, Marcus. The Zeppelin, Carl.

What began as a Led Zeppelin Revival extension is now, in Baldassarre’s eyes, a possible make-your-mark project.

A few months ago, Baldassarre hosted a Led Zeppelin Revival show at the Grog Shop, a sort of precursor to July’s souled-up version with Scott. For two and a half hours, Baldassarre, with his unkempt ponytail and bell bottoms, leaps around the stage handling his 1974 sunburst Gibson Les Paul. Just like Page, he soloes during “How Many More Times” with a horsehair violin bow. Hammering out soaring string bends, he nods to singer Guy Snowden in ecstasy. He looks, it’s probably obvious to say, pretty happy. “He’s like a 16-year-old kid with a dream,” says Joey Varanese, Baldassarre’s booker.

After the show, Baldassarre addresses the question that’s been gnawing at him: How can he make sure his work is good enough to release to the world?

“Polished music comes from absolutely immersing yourself,” he says. “If you’re going to be an artist, you have to be all in.”

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5