The Reluctant Redeemer

by Jeff Hedrich | Nov. 14, 2019 | 1:00 PM

Fame is coming to Bernie Kosar with an open mouth and he knows that mouth is ravenous. But how much could one kiss hurt? He has to make a choice; accept fame or shun its seduction. Kosar seems to want to make both choices. But the decision isn't his alone. A city and its people want to make it for him.

On a sunless morning in May, the elementary school of the Catholic parish he habitually attends is holding a kind of ceremony of adoration for Kosar. In a gym strewn with orange and brown balloons and posters, 400 children sit cross-legged on the floor, so quiet I look to see if their mouths have been sewn shut. Kosar saunters in and the quiet breaks like a vase, children's voices spilling everywhere; I half expect the nuns to form a police line to protect Kosar, swinging rulers instead of billy clubs. Kosar grabs a microphone and paces in front of the stage, joking, laughing, and answering mostly personal — How much beer can you drink? Never mind, and stay away from the stuff — questions. Several times Kosar looks over and asks that I don't write down his answer. The only question he doesn't answer is from a boy who asks how much money he makes.

A kid who looks like a miniature, chubby version of Woody Allen asks Kosar to sing Bernie, Bernie, a song about Kosar that received extensive airplay the last two seasons. "There isn't a chance of that happening," Kosar says, but he convinces the chubby kid and a friend to perform their rendition of the song. He lifts the children onto the stage and they dance and belt out a version complete with mimicked guitar. The crowd goes wild, Kosar is near tears with laughter.

Kosar is comfortable with children because he trusts that their admiration for him is genuine. But many adults want a piece of Kosar and don't care how it's extracted. He goes to parties and is strafed by investment schemes piloted by drunken strangers. Women have come at the 24-year-old millionaire like bears trying to tear a sapling from the ground, wanting to get at the sweet green root of all evil. "Who knows what some people see," Kosar says, "when they're looking at me."

Kosar doesn't often discuss the disquieting side affects of fame and wealth. He believes he's blessed and has little to complain about. Neither is he enthralled with talking about his blessings. "It's like my dad says — 'I is the most boring word in the language.' I get sick of having to talk about myself."

But how much longer can Kosar carry the image of a man disengaged from his fame?

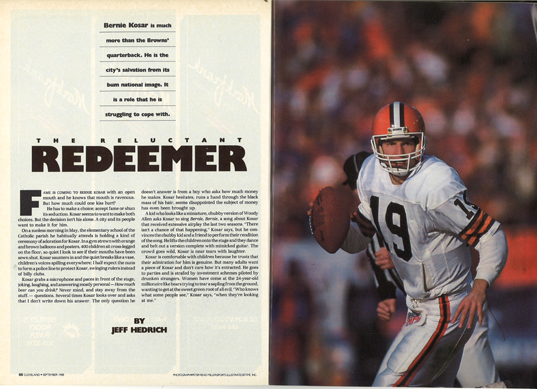

The Cleveland Browns pay Bernie Kosar more than $1 million a year to play quarterback, perhaps the most glamorous occupation in professional sports. His predominant skill is throwing a leather ball amidst a field of men beating the hell out of one another. But he has put himself in the position of being a hero in a city famished for one.

Everyone who knows Kosar agrees he doesn't crave public attention, doesn't need it to slake his vanity.

But look at publicity photographs of Kosar taken during his first couple of seasons with the Browns. Or recall that embarrassing electric heat pump commercial with Kosar sitting in his living room, dressed up in his full uniform. In those first years he always looked like his smile had been hammered into his face, like he was trying not to show how repulsed he was by being in front of a camera, by being a celebrity.

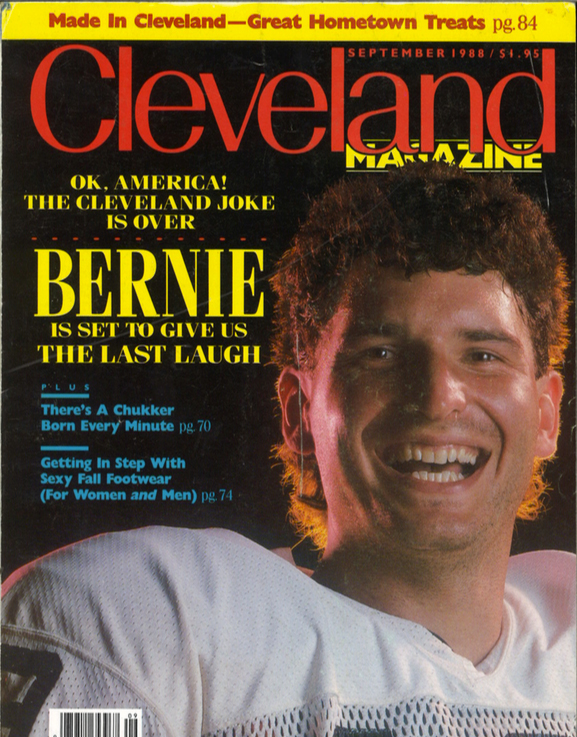

Then consider his more recent photos or commercials, the cover of this magazine.You find it in his voice and in his expression: He appears relaxed, confident, almost ballsy; he looks like he's enjoying himself.

As I'm leaving the elementary school with Kosar a nun takes me aside, admonishing, "If you find out anything bad about Bernie, we don't want to know about it." Kosar rides with me to a restaurant where he eats three or four times a week because he can't cook; I'm imagining what it would take to shock the nun and decide it wouldn't take much. The simple disclosure that Kosar could be human, with a small, controlled lust for fame.

In the midst of his meal at the restaurant, a woman smoking a cigarette, a big swab of white hair rising from her head, comes to the table and starts firing praise and accolades at Kosar. She tells him he's the best thing that ever happened to Cleveland. Kosar can't remember the last time he dined in public uninterrupted. For his friends, going to a bar in the Flats with Kosar and hoping to be left alone is like lying out at Edgewater beach with bread crumbs on your chest and expecting the gulls to respect your privacy.

If Kosar does luxuriate in the attention, it's not often visible. As the woman raves on, his expression is bored, contemptuous. Kosar is still getting used to being a sports figure and celebrity and now he's evolving into something more, and part of him wants to ignore it. People see him as a hero, a person in whom they've invested something of themselves.

He's a hero in Cleveland because people believe he's one of us, he chose to remain one of us, he can win for us.

It's as if we've dreamt Kosar into being as part of some myth of redemption for the city. He's aesthetically perfect as the quarterback of Cleveland's football team. He grew up here; he's ethnic; his father lost his job as a foreman in the steel mill during the last recession; he's endured jokes about his lack of physical grace. Cleveland is an ethnic city, was devastated by the recession, its physical appearance has been endlessly maligned.

In a myth, a hero embodies both the strengths and weaknesses of his culture. The hero undertakes a quest in which the strengths of the culture triumph despite its weaknesses.

In the last quarter of a century, Cleveland has been less than exalted among the nation's cities. It is portrayed as a barely living hell; a river on fire, a school system on its knees, poverty as a growth industry, apartheid politics, the first city in the country to go into default since the Great Depression. And one more thing. The professional sports teams have usually been rank.

But if Bernie Kosar leads the Browns to their first championship in almost 25 years, all of that heartache — briefly, absurdly, truthfully —won't matter.

Perhaps the Flats are feeding the city's starving nightlife and downtown development is manic. But people have to come to Cleveland to see and believe that. Professional football's medium is national television; the screen a frame in which each play is hung for several seconds, a painting of brutal, engrossing human behavior. About 125 million Americans watch the Super-bowl every year.

And there is something ancient and territorial about the game. Each city in the National Football League sends 45 physically gifted men into public arenas to try to dominate men from another city. In the aftermath of a victory, Cleveland can say to the media empires of New York and Los Angeles — Bernie isn't a pretty boy, and we aren't glamorous, but we kicked your ass.

In this myth of redemption, Kosar triumphs for the city because he embodies a beloved cultural strength: Faith in the work ethic.

Kosar got his faith in the work ethic the old-fashioned way; he inherited it. Kosar and his younger sister and brother were raised by their parents according to the principle of love and exhaustion: If you love your children, keep them busy and keep them tired so that you keep them out of trouble.

The Kosars are a tight family, seem to all be woven of one flesh. Cut one and everybody might start bleeding. Geri Kosar, Bernie's mother, is as sweet and reticent as Bernie's father is gregarious. Friends say Bernie is a hybrid of his parents but that his father is his task master.

Bernie Kosar Sr. is a big man with a raw, broad face, silver and black hair, glasses, a working man's muscled forearms, a salesman's handshake, a beeper hanging from his belt like a pistol; the kind of guy men in the mill said was "A man's foreman... a son of a bitch who got right down there with you"; the kind of guy who goes to Mass with his family every Sunday, but can ignite when he's mad at you; the kind of guy who, when the mill shut down, successfully sold industrial air compressors in a part of the country where the market had disintegrated; the kind of guy who could raise a son to have the self-assurance of a fist.

Kosar Sr. still sells air compressors but he spends most of his time managing a venture capital firm that Bernie and he own. The firm's office is near the Kosar's home in Boardman, a suburb of Youngstown, little more than an hour southeast of Cleveland. Plaques and commendations, most of them Bernie's, swarm the office walls. Kosar Sr.'s favorite is a photograph of Ronald Reagan throwing a football from the doorway of Air Force One. "It's inscribed to Bernie," he says, a smile almost dislocating his jaw. "Bernie met the president this past year. I've come home to find messages on the answering machine from Jack Kemp, Albert Gore. I just lose it."

When Bernie was a child he went to Browns' games, sat in the upper deck, swallowed stories of the golden days poured out by his father; Otto Graham, his father said, threw passes higher than the Stadium that would float the length of the field and fall into the arms of a human deer named Dante Lavelli. Innumerable boys grow up in and around Cleveland desiring to play for the Browns. For Bernie that desire attained a mass that gave it the weight and momentum of an obsession. His obsession was given credibility by his father's faith that hard work was the going price of any accomplishment.

In his senior year of high school, Kosar was the finest quarterback in Ohio. Awards came like rain. Some colleges disdained Kosar because he was slow, gangly and, despite his accuracy, did not have a classic throwing motion. It sometimes appeared he thought he was throwing a javelin or skipping a stone across a lake. "Basically, he was kind of skinny and geeky for a quarterback," a high school friend says. His throwing style as a professional is still mechanically unorthodox, given to improvisation. "Yeah, but the one thing Bernie's always known how to do perfectly, " says Dave Redding, the Browns' strength and conditioning coach, "is beat you."

Kosar wins at almost everything. Blackjack. Poker. Lawn darts. Stupid bets involving stupid feats. He has cement calves but wins one-on-one basketball games against players who can dance in the air. He wins because he's obsessed with winning or because — according to a couple of the Browns who lose continuously to Kosar—he made an arrangement with Satan. At a recent charity banquet, the audience wagered on which of about 10 NFL quarterbacks — including Kosar, Dan Marino, Jim Kelly, Boomer Esiason—could throw a football through a tire the most times out of five tries. Kosar hit five for five, no one else was successful more than once.

All of this comes back to his father. "If I make a hundred sales calls I expect to close a hundred deals," his father says. "If I don't, I'm disappointed in myself. I want to know what I did wrong. I want to correct myself...." As he continues, I imagine a parade of Believers marching through his office: Amway salesman, the United State Marine Corps, Norman Vincent Peale, Dale Carnegie, Up with People, Vince Lombard!, all holding hands and then saluting Kosar Sr. as they pass by for inspection. The weird part is I'm not laughing. Mr. Kosar, I almost ask, do you think I have what it takes to sell industrial air compressors?

"Look," Mr. Kosar says, "whatever I'm doing, I want to win. Say my wife and I are playing cards with another couple. Sure, I suppose I enjoy the fun of the game and the company. But if you're going to take the time to play the game, why not win? Why not win?" But what's the big deal, I ask him, about winning a game in which nothing is really at stake? Mr. Kosar is quiet for a moment, a little stunned, can't or won't imagine an answer to the question.

And because his son knew how to win and was a pressure junkie — the more important the game, the better Bernie Kosar played—the University of Miami rated him as one of the three best high school quarterbacks in the country. Kosar signed with the Hurricanes, was redshirted as a freshman — he practiced but saw no varsity action and so didn't use any of his four years of eligibility — and went into spring practice as the third string quarterback. Not a big tragedy in the pageant of human events, but hard to accept when you're addicted to being the man.

But in spring practice Kosar dissected every defense he faced. Over the summer he worked out six hours a day and wore away a path of grass next to his parent's house while practicing his drop backs. By the end of fall practice Kosar was the starting quarterback, beating out an eventual Heisman trophy winner, Vinnie Testaverde.

In the two seasons Kosar started for, the Hurricanes he established 22 single game, season, and career records. In his first season, Kosar directed Miami to the national championship, defeating Nebraska in the Orange Bowl.

But it was a game during his second college season that convinced a lot of people that Kosar had the ideal temperament to be Cleveland's quarterback. In a nationally televised game, Miami called a time out in the fourth quarter with fourth down and goal to go against Boston College. Kosar came to the sideline to talk with his coach, his hair shining like dark leaves in rain, his face contorted with anger, his pupils like bright black stones. A network camera and microphone recorded the suggestion Kosar screamed into his coach's ashen face: "Let's run the fucking football!"

"Yeah, I liked that," says Browns' majority owner Art Modell, laughing. "It showed me a young man with — conviction."

Little more than half a year after the Miami versus Boston College game, Modell would sign Kosar to the most lucrative contract in the team's history. At that time Kosar still had two years of athletic eligibility at Miami. Like lovers going to great lengths to be with one another, via desire and wile the Browns and Kosar manipulated the NFL's drafting procedures to their mutual benefit.

Entering his first training camp with the Browns, some thought Kosar would be a big stiff and others predicted he'd become a legend.

The Browns started the season with veteran quarterback Gary Danielson, part of their plan to bring Kosar along slowly, to prevent him from being ripped up until he was ready. But Danielson got hurt in the season's fifth game.

Kosar came onto the field with a jock's loose careless strut and the crowd at the Stadium went crazy. He lined up in his weird, endearing sidesaddle stance, barked his signals, took the snap, fumbled the ball. He tried to gently pick it up as if it were a baby lying asleep in a crib. He got knocked on his butt, and the defense recovered the fumble.

The crowd wanted to stone Kosar, believing he was another false prophet come to lead Cleveland from the wilderness into the darkness. "It was the most embarrassing thing that ever happened to me," Kosar says. "Seventy thousand people screaming my name and then 30 seconds later, they all turned on me. I'll never forget that."

But Kosar came back into the game, completed seven passes in a row and the Browns went on to win. All was forgiven.

The Browns finished the season with eight wins and eight losses. They lost, barely, to Miami in the play-offs. But Kosar only threw for 66 yards. He bitched about it. I got a gun and I want to fire it, was essentially his argument.

Some in the media felt, and wrote, that he had a pretty big mouth for a rookie. And they weren't convinced just what kind of gun he was carrying.

Maybe a BB rifle. But it turned out Kosar's arm wasn't a gun at all. It was a launching pad. And during the last two seasons he's destroyed almost every defense he faced. He's directed the Browns to the AFC championship game both years. But regardless of how dramatic those two championship games against Denver were, regardless of how impressively Kosar played, the unchangeable fact is that Cleveland lost.

"Devastating, absolutely devastating," Art Modell says, sitting behind his big desk in the Browns' headquarters in Tower B of Cleveland Stadium. He talks of those two losses as if they are two children he has lost, each in some terrible accident, one year apart from the other. He stops talking about his grief for a moment to take a phone call from Senator Howard Metzenbaum. He resumes his mourning. He's beckoned into the hall for a hushed discussion about tax abatements and the Stadium's lease with the city. He comes back in and starts talking again about what he really cares about.

There are pictures on the wall of Modell with Henry Kissinger, Gerald Ford and others. The Browns will go on receiving $ 16 million a year in television rights and almost that much more a year in ticket sales and other revenue whether the Browns win the Super Bowl or not. But sitting behind his big desk in his opulent office in his expensive suit, there is something starved about Modell.

He wants a championship like we all want the thing we think will bring us the respect we deserve.

"I fully expect Bernie Kosar to be the best quarterback I ever had, ever will have," Modell says. "The intelligence, the leadership, the arm. He has everything. Everything including magnetism I haven't seen since Jimmy Brown. People are attracted to him, something in his presence."

I grew up not far from Kosar, played football in the Steel Valley Conference (the name tells you everything necessary about where we grew up; what it looked like, what was important to us) about the same time he did, was one of the innumerable boys who wanted, dreamt of playing for the Browns.

The dream embarrasses me now. I held onto it for too long after I'd seen the evidence that it couldn't come true.

And I've become a little embarrassed of the game, its primitiveness, and its giving to violence the shape and cadence of a dance, giving violence a grace not deserved.

But a dream of that longevity becomes lodged like a pearl in the subconscious's recessed folds; and of course I wonder what I would be like had the dream been realized. Kosar's dream is opening into a reality that exceeds my dream in texture and detail. Billboards along the city's interstates show a massive Kosar throwing a football scarfed in flames. Promotional brochures say Catch Bemie and the Browns, in that order, like an author who's name is featured above the title of his play because he's become, for some people, more important than his work.

The first time I approached Kosar to ask and write down what it was like to live this dream, he was naked and sopping, striding through the Browns' summer training [camp locker] room. Sports-writers make their living (interviewing nude men so I thought I could go through with it, once. I couldn't; Kosar was naked but I was the one who felt ridiculous. I tried to explain to him the idea for the story, and he just looked at me, bored, contemptuous. He said he didn't have time, didn't know when he'd have time, didn't like doing this kind of thing, maybe later.

This past spring I approached Kosar again in the locker room of the Browns' spring camp at Baldwin-Wallace College. "I don't want to do it," he said. "Some local magazine did it last year and they wanted a lot of time and printed these dumb little anecdotes about me growing up. Who cares about that stuff?" I pressed, explained and blackmailed him by talking about Youngstown and growing up there and playing football and needing to keep my job. "All right," he said, "but I know you don't just want to ask questions about football. Just try to keep it simple and don't get too personal."

During the course of this story I spoke with more than two-dozen people about Kosar and if they had anything bad to say about him they weren't giving it up. The only one who gave Kosar even the scent of something human was Tony Grossi, The Plain Dealer's pro football writer. Kosar had told me he doesn't read anything written about him, but Grossi says, "Ah, he's full of it. He likes that 'I only read the Wall Street Journal image,' but he's given me hell for some of the things I've written about him. But listen, he's the most genuine, authentic human being you'll ever meet. He's just not into the fame. He's known as the worst interview in pro football. He loves that reputation. He'll hang up on interviewers if they ask a dumb question. He'll laugh after he hangs up. He gets off on it."

Kosar says that as recently as a year ago he only felt famous in Ohio and Florida, the two places he's played football. Now, since last season's AFC championship game, almost anywhere he goes in the country he's recognized and sometimes mobbed. In a national contest voted on by the fans, Kosar was chosen the NFL's Most Valuable Player.

Will proliferating fame change Kosar from the genuine, authentic person everyone seems to believe he is? Kosar and everybody else say no.

But after the adoration ceremony at his parish, sitting in my car, Kosar rather shyly showed me an envelope. Inside it was a letter from GQ, the men's fashion magazine. "This blows my mind," he says. "They want me to pose. Uh, for the cover. I didn't want to do it at first but kind of got talked into it." Then Kosar laughed. "It's funny because people are always getting on me about the way I dress."

How can Bemie Kosar not change? How can you be a working-class hero and be the cover boy of a magazine that worships money and style? Kosar says money hasn't changed him because he knows that money doesn't make you happy, people do. But the kind of money he makes does relieve him of many of the everyday responsibilities most people have. How can you make more than a million dollars a year, be the highest paid football player among Converse's product endorsers, have presidential candidate Jack Kemp calling you for an endorsement during the primary season, have women who don't know you offering themselves — how can you be 24 years old and going through all that and not have changed and be changing?

And Kosar has already been put on the civic lathe, is being shaped into something more than an adulated jock. He's an active, contributing member of Cleveland State University's blue ribbon committee on athletics and academics — a committee stocked with some of Cleveland's most influential business and civic leaders, formed in response to the NCAA's investigation of the school's basketball program. Some already talk of Kosar's future as a political candidate, talk he's engendered himself by openly discussing his love of politics, his belief that the leadership skills required of a professional athlete are the same-as those required of a political leader. The reluctant hero is losing, selectively, some of his reluctance. It doesn't mean he's no longer a genuine, authentic person. But it's clear he's becoming more conscious of his public responsibilities and opportunities.

Just before summer training camp opened I drove out to Big Creek, the Browns' off-season training facility, to see Kosar and arrange a photo session. He was about as happy to see me as you would be to see a state trooper at your door at dawn when your daughter still hasn't come home from the prom. I stayed to watch Kosar work out; he was ecstatic to be among the boys, laughing, snapping towels, throwing obscenities at one another. Just as Kosar is transforming his public presence, he's altering his body: He looks more graceful, has assumed a lean musculature, he bench presses 80-pound dumbbells in sets of 10 repetitions, walks with an athlete's insularity — that sense that whatever trouble he gets into, his body can get him out of it.

After more blackmail and haggling he agreed to give a photographer 10 minutes of his time at the Browns' summer training camp at Lakeland Community College. A camp the Browns hope will prepare them for the Super Bowl, the grail in the myth of redemption. On the second day of summer camp, Kosar walked through a gauntlet of fans from the practice field to the locker room. People called out his name repeatedly as if it were a mantra, children reached out tentatively to touch him, a woman offered to have him autograph her chest.

In an improvised studio secluded, as Kosar prefers, away from his teammates, he posed for a photographer in his pads and practice uniform. A reporter from Sports Illustrated hung around like an obedient dog, waiting for Kosar to finish.

The photographer cajoled Kosar to loosen up, become more animated. Kosar, laughing, started to do a little dance.

"Watch it," the photographer said, "you might ruin your image."

"Yeah?" Kosar said, smiled and then made a remark that could have been rhetorical, a sincere question, or something he was asking himself out loud. "What is my image?"

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5