They were the princes of the gridiron.

And as Cleveland’s best high school football players and heavily recruited athletes, Eugene Smith, Jimmy Weiler and Gary Jeter were treated like kings. (They were also the subjects of a 1973 Cleveland Magazine piece on aggressive recruitment of high school athletes by college athletic departments.)

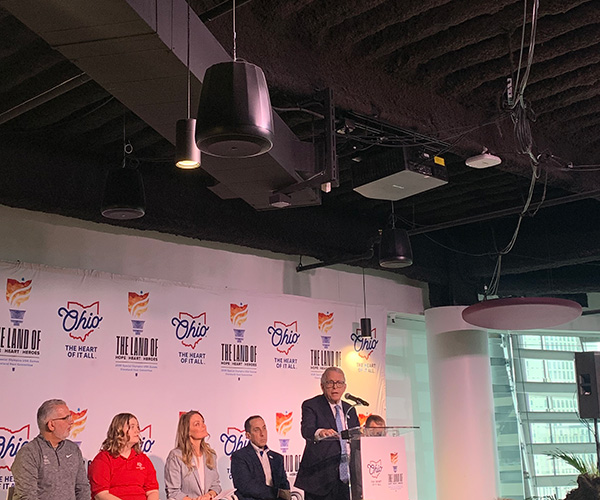

Today, Smith, the athletics director of The Ohio State University, sees the issue from another side, albeit one informed by his role as the sought-after athlete.

“I’ll never forget the recruiting process I went through,” he says, ticking off enticements such as cash, access to apartments and summer jobs that paid well above market value.

Smith chose the University of Notre Dame, where he played defensive end and won a national championship. He continued as a coach after graduation and served on committees charged with developing new rules for recruitment. “It’s a lot cleaner now,” he says.

In-person visits to college campuses are limited compared with the dozen or so schools Smith and Jeter checked out.

“We didn’t travel a whole lot,” says Jeter, a manager of business development for a Florida-based security firm, “so I used the recruiting process to see the whole country. I went to 10 places.” He works out of North Royalton and announces high school football games for FSN Ohio.

Jeter selected the University of Southern California, not for the enticements, but because he knew the team had been a “who’s who” of college football.

A first-round draft pick of the New York Giants in 1977, Jeter played 13 seasons as a defensive tackle in the NFL.

Like Smith, Jeter has also gained a new perspective on recruitment. His daughter, Kayla, is a heavily recruited high school volleyball star.

“It was kind of overwhelming,” he says of the schools contacting Kayla, who verbally committed to Tennessee as she entered her senior year of high school.

Jeter’s high school friend and Smith’s Notre Dame teammate Jimmy Weiler entertained thoughts of pro football until his junior year, when he started getting four or five “burners” — sharp, radiating pains — each game. “I realized at that point I was not going to make a living playing football,” he says.

Instead, Weiler made a living in sales. His tousled locks, prominent in the photos from 1973, are gone now. It is ironic considering his current job with a drug-testing company in Chicago. “Of all things,” he laughs, “we do hair analysis.”

Weiler says there may be more pressure on athletes now than when schools were pursuing them in the early 1970s. “Today, I get the impression these kids can’t come up for air,” he says.

“There were a couple of schools where you had a very attractive host [for your campus visit],” he recalls. “Notre Dame was not one of them.”

His host was a Fighting Irish defensive end.

And as Cleveland’s best high school football players and heavily recruited athletes, Eugene Smith, Jimmy Weiler and Gary Jeter were treated like kings. (They were also the subjects of a 1973 Cleveland Magazine piece on aggressive recruitment of high school athletes by college athletic departments.)

Today, Smith, the athletics director of The Ohio State University, sees the issue from another side, albeit one informed by his role as the sought-after athlete.

“I’ll never forget the recruiting process I went through,” he says, ticking off enticements such as cash, access to apartments and summer jobs that paid well above market value.

Smith chose the University of Notre Dame, where he played defensive end and won a national championship. He continued as a coach after graduation and served on committees charged with developing new rules for recruitment. “It’s a lot cleaner now,” he says.

In-person visits to college campuses are limited compared with the dozen or so schools Smith and Jeter checked out.

“We didn’t travel a whole lot,” says Jeter, a manager of business development for a Florida-based security firm, “so I used the recruiting process to see the whole country. I went to 10 places.” He works out of North Royalton and announces high school football games for FSN Ohio.

Jeter selected the University of Southern California, not for the enticements, but because he knew the team had been a “who’s who” of college football.

A first-round draft pick of the New York Giants in 1977, Jeter played 13 seasons as a defensive tackle in the NFL.

Like Smith, Jeter has also gained a new perspective on recruitment. His daughter, Kayla, is a heavily recruited high school volleyball star.

“It was kind of overwhelming,” he says of the schools contacting Kayla, who verbally committed to Tennessee as she entered her senior year of high school.

Jeter’s high school friend and Smith’s Notre Dame teammate Jimmy Weiler entertained thoughts of pro football until his junior year, when he started getting four or five “burners” — sharp, radiating pains — each game. “I realized at that point I was not going to make a living playing football,” he says.

Instead, Weiler made a living in sales. His tousled locks, prominent in the photos from 1973, are gone now. It is ironic considering his current job with a drug-testing company in Chicago. “Of all things,” he laughs, “we do hair analysis.”

Weiler says there may be more pressure on athletes now than when schools were pursuing them in the early 1970s. “Today, I get the impression these kids can’t come up for air,” he says.

“There were a couple of schools where you had a very attractive host [for your campus visit],” he recalls. “Notre Dame was not one of them.”

His host was a Fighting Irish defensive end.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d67cfd8c_1&w=640&auto=compress%2cformat)