Inside Northeast Ohio's Most Competitive Youth Sports Leagues

by Dillon Stewart | Aug. 24, 2023 | 11:00 AM

Casey Rearick, Collin Taylor, Anita Robertson, Courtesy The National Basketball Academy, Courtesy Okicki Hockey

I’ve asked to chat with her son Gregory Price, a sophomore on Hawken School’s high school basketball team, about the lessons, trials and tribulations that come from playing highly competitive youth sports. But they’re busy, like they always are on Tuesday nights, driving home from an open gym.

Even for those who might have played high-level high school sports as recently as a decade or so ago, the phrase “youth sports” probably conjures up lazy summer evenings of sloppy baseball at a poorly kept local diamond. But for thousands of Northeast Ohio children like Price and parents like Malone, whose families participate in club sports on the highest level, the stakes are higher than ever.

The National Council of Youth Sports says more than 60 million children participate in sports in some form and about 27% specialize in one. In 2022, youth sports was estimated to be a $37.5 billion global industry, according to Markets N Research,

and by 2030, it’s expected to

nearly double, to $69.4 billion.

The growth of this industry has created a never-ending search for the trainer, showcase, team or tournament that is going to give Jimmy or Suzy the edge over their competition. This leads to athletes training like pros long before they’ve even hit puberty.

(Photo courtesy Casey Rearick)

But what is the cost of this athletics arms race? Some national surveys estimate the price tag of putting one child through one sport at about $600-$800 per year, and more than 60% of parents

reported in 2022 that youth sports put a financial strain on their families. Yet, depending on the sport, the parents, coaches and trainers we spoke to explained how the cost often balloons to more than double that per year. Many sports,

such as tennis and baseball, can cost closer to $1,000 per month, and in extraordinary situations, families might spend upward of $25,000 to $50,000 to play tournaments year-round and work with specialized coaches.

But the cost can be far more than just financial. According to the Cleveland Clinic, more than 50% of the sports-related injuries they see come from overuse, and multiple studies show that specialization — or focusing on just one sport — makes sports injuries, including shoulder and elbow injuries in baseball, elbow injuries in tennis and knee injuries in volleyball, more likely.

While some studies find that sports can be a boon for mental health, many athletes and parents we talked to shared stories of burnout. About 35% of elite athletes reported experiencing conditions like disordered eating, anxiety and depression, according to the American College of Sports Medicine. Often, parents play a role in this.

So if that’s the cost, what’s the payoff?

“Playing at the highest level,” says Price, referring to something less than 2% of high school athletes achieve. “Playing Division I. That’s always been my goal. I’ve thought about it since I was a kid, but I’m only now really understanding what it takes.”

But first, Price has to get his driver’s license.

When I call, Malone is riding shotgun and editing video clips for Price, who is driving them home from the gym.

Malone films almost every practice and game to help feed Price’s social media accounts, which are dedicated to the 6-foot, 170-pound point guard’s highlight reels and curated to keep the attention of college scouts.

“Give me, like, two minutes to help him pull into a parking space,” she says.

Price’s 16th birthday in January would be a milestone for any parent. But for Malone, it will also mean a little more independence and a little bit of relief.

On an average week, the single mother must navigate getting her children to no fewer than four and as many as seven practices — not to mention potentially 10 games over a weekend if both of her sports-active kids (her third child is 3 years old) make runs in tournaments, which are often out of town. She works full time in the supply chain at Moen, the faucet and home fixture company headquartered in North Olmsted.

“Every once in a while I just say, ‘I need some time to myself,’” she says. “So I’ll schedule a spa day or a girls trip.”

Though he’s now in high school, playing for Hawken’s varsity basketball team, Price still plays in the Amateur Athletic Union, a sports governing body better known as AAU, most of the spring and summer. Founded in 1888, the organization oversees gymnastics, wrestling and more, but it’s most closely associated with basketball thanks to that sport’s more than 700,000 active member athletes.

AAU membership, which typically costs about $600, grants players access to hundreds of tournaments across the nation with the best talent one can find, and teams are often about an additional $1,000. Price often plays about two tournaments a month, which in the past year has taken him to Columbus, Cincinnati and Indiana but never once kept him in Cleveland. Hotels average about $250 with the tournament rate and sometimes players can get disqualified if they choose a hotel other than the sanctioned one. Altogether, a season could easily cost $4,000-$5,000 — and basketball runs cheap compared to volleyball, tennis and hockey.

Malone has worked to minimize costs by packing snacks and Gatorade, by staying with friends and family who live near the tournaments and by joining teams that limit travel outside of the region.

“I have to budget for that!” says Price. “I typically get my tax refund check in February right before the season starts in March so I can use those funds to pay for the costs.”

Don’t get it twisted; Price’s dedication shows. Likening his work ethic to that of the late Kobe Bryant, he goes hard in the gym. Last year, he even played varsity basketball as a freshman.

But even he can recognize the secret weapon in his corner.

“I think my mom has done more for basketball than what I’ve done for basketball, and I work on it all the time,” says Price. “I feel like she did everything I could have asked her for, and that’s just really the great thing about it. I mean, having a mom that was at all your games, recording them, helping — she did everything she could have done to put me in the best position possible.”

Putting their kid in the best position to succeed on the field or the court — that’s why parents come to T3 Performance. For more than 12 hours a day, seven days a week, black rubber pellets fly from the blue turf of the well- over-100,000-square-foot Avon Lake athletic complex, as hundreds of athletes from ages 7 to 20 years old train for anything on grass or turf, as its trainers say. The company’s new spot at University Hospital’s Ahuja Medical Center in Beachwood is helping it expand to the court, too.

T3 has produced dozens of Division I college athletes and even a few pro athletes. Book a session and you might be working out next to 6-foot-5 offensive lineman Devontae Armstrong, a two-time state champ at St. Edward High School and a three-star recruit committed to Ohio State University; or Mackenzie Russell, a midfielder from Rocky River continuing her soccer career at University of Dayton.

(Photo courtesy Collin Taylor)

While T3 has plenty of success stories, these days, trainer Collin Taylor is much more interested in something else.

“What moves the needle the most is developing the human being,” says Taylor, “putting athletes in situations where they feel comfortable failing.”

As one athlete gears up for an epic power lunge of 500 pounds, Taylor, who can often be seen jumping off the turf and walls in his signature cutoff T-shirt, pumps up a crowd around him. The athlete’s teammates bounce up and down and hoot and holler as the young man pulls the bar off the rack. As the powerlifter switches from a left-foot front lunge to a right, Taylor immediately puts his chest to the powerlifter’s back and scoops both arms under his armpits for an extremely active safety spot. The athlete quivers upon the second drop but ultimately returns to his base position. As he re racks the weights, his teammates descend upon him in an embrace to celebrate his weighty achievement.“Training is failure over and over and over again with the idea that,” Taylor says, “by the time you get to the game, you’ve failed enough to where you feel comfortable giving the amount of effort that it takes to succeed in that high-level, high-stress situation.”

The native of Carmel, Indiana, grew up a sports nut who got by in school and watched SportsCenter only when it got too dark to keep shooting hoops. A four-sport athlete, Taylor went to Indiana University, where he played on the Hoosier football team. After college, the defensive back and wide receiver ended up in Northeast Ohio, playing for the now-defunct Cleveland Gladiators of the Arena Football League from 2014-2017 before winning a championship in 2019 with the Albany Empire. Once COVID-19 hit and the AFL went bankrupt, he moved back to Cleveland to work with T3 Performance.

(Photo courtesy Collin Taylor)

Today, many football parents seek him out due to his background, but he deals with athletes of all types. He deals with parents of all types, too.

“I’m getting these parents who want to train with me five, six, seven times a week,” he says. “I’m trying to tell them that I’ve done this a long time — and, you know what’s better than bringing your kid in for a 9 p.m. weightlifting session after he’s done a double day at basketball practice in the morning and football in the afternoon? Instead of paying me $100, why don’t you get him to bed at 9 p.m. and let him sleep for 10 hours? And very consistently the parents will say, ‘Yeah, I appreciate your opinion, but we’re going to go ahead and book that session at 9 p.m.’”

Taylor’s voice rises and his words grow more rapid as he tells me story after story of bad-behaving parents. He apologizes if he was rambling through our nearly two-hour conversation.

Often, once an athlete has warmed up and their parents’ attention is diverted, Taylor asks two simple questions: “How are you feeling? Are you enjoying this?”

Away from their parent’s influential ear, the answer is often no. In fact, studies from the National Institute of Health show that one of the biggest factors that diminishes a child’s love of the game is parental pressure.

Anita Robertson still remembers the moment when her daughter’s relationship with tennis changed.

Facing yet another out-of-town tournament, Samantha, who was in her early high school years, had put in the work. She attended extra training sessions each week and approached every drill with intensity. She’d done everything her parents and coaches told her. Still, when it came time to compete, the ball just simply wasn’t falling her way.

“She was just feeling so much pressure and not getting the results she wanted,” says Robertson. “There was a point where she was just not enjoying it at all. It was like she hit rock bottom.” But it didn’t happen all at once. Robertson admits to, at times, being that mom. After frustrating losses, she’d wonder aloud in front of her daughter: What are we not doing right? Are we doing enough? Why are we spending all this money? For as many travel dinners made memorable by the good times, just as many were marred by frustration.

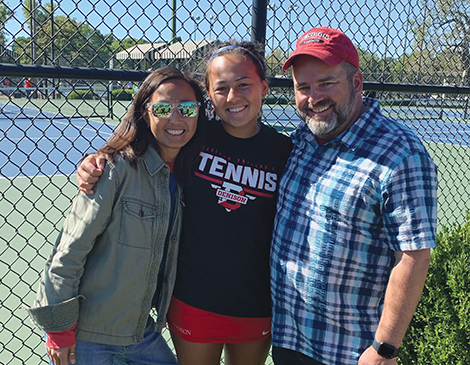

(Photo courtesy Anita Robertson)

“I’ve gotten much better, but I’ve made my share of mistakes. I would get really caught up in the intensity of these high-level tournaments,” says Robertson. “I would just keep pushing and pushing, but eventually, I realized no matter how hard we pushed, it just seemed like there was some parent doing so much more. It’s cutthroat.”

Robertson played tennis herself all the way through college. She also played basketball and ran track. Nathan, her 20-year-old son who did not go on to play collegiate sports, shared that generalized experience by playing golf, football, basketball and lacrosse. Yet, around 10 years old, despite staying in basketball until high school, both her daughters — 22-year-old Sarah, who played at and graduated from Denison University, and the 18-year-old Samantha — found that they had to focus on tennis year-round in order to keep up.

In 2013, the National Institute of Health found that 70% of tennis players specialized by an average age of 10.4 years old. This year, it found that those who do specialize at a young age are more likely to have tennis-related injuries than most other sports.

Most tennis players, at least locally, start by joining a country club. In the Robertson’s case, most of the girls’ careers were headquartered at Cleveland Racquet Club in Chagrin Falls, which offered a junior membership so the entire family wasn’t forced to join. She ballparked that the junior membership cost about $200. Then, each coaching clinic session, of which there were about three or four a week, cost about $40, with special lessons from pros costing closer to $80 per hour. Tournament fees are typically about $100 apiece, and there are tournaments to play every single weekend of the year, if you’re willing to travel. Add it all up, and your starting price is about $1,000 per month.

For many tennis players, perhaps an even bigger driver than collegiate dreams is the number that hangs over their heads. Yes, other sports have MaxPreps or Hudl, but in sports like tennis and hockey, algorithmic rankings decide who you play and how scouts view you.

Over the years, various ranking systems have become trendier than others and depending on the scout or tournament, one might be more important than the other, but the main benchmarks are the newer World Tennis Number and the Universal Tennis Rating, which allow players to rank themselves against everyone from a novice in their first match to Serena Williams.

The rankings don’t just give insight to scouts; they determine which tournaments you can get into. Naturally, parents work to game the system by having their kids play tournaments every single weekend, attending lower-bar tournaments just to pick up easy wins and even encouraging their children to cheat on close line calls, which rely on the honor system.

“My daughter’s UTR was, like, a low eight, and she was talking to a college that said, ‘Oh, we’re looking for a high eight. She’s a junior, so maybe she could get it up,’” says Robertson. “These girls would be working for literally a year to get their numbers up by a hundredth of a point.”

When brothers Tim and Alex Okicki grew up playing hockey, there was one objective: to win the game.

Today, as they operate Okicki Hockey, a local organization that hosts summer camps and specialized training in various locations, there is another goal that looms over each team.

Neil Lodin of Indianapolis founded MyHockeyRankings and first published its ranking website in the 2003-2004 season. After finding out that a simple win-loss record didn’t always accurately represent how good it was, Lodin started the site to help his son Ian (who now helps him operate the site) seek out better competition in other cities. Today, more than 300,000 visitors flock to it each month to see where their child and their team ranks nationally among more than 24,000 teams. Each year, the website awards a player of the year, and the rankings include teams as young as 10 and under.

“The sad thing is that people really care about it,” says Tim Okicki. “I’ve heard parents tell me that they’re waking up at 6 a.m. on Wednesday mornings (when the website is updated) just to check the latest rankings.”

The rankings are determined by an algorithm, which basically calculates average goal differential versus strength of schedule — or, as the website puts it, “how well they play against other teams and how good those teams are.” The 30-question FAQ page is enough proof that many players, coaches and parents are extremely interested in knowing how the system works — and then gaming it. Still, the rankings are the most commonly used resource for determining a team’s schedule, and while USA Hockey helped drive a 2022 change to the site that removed numerical rankings from under-12 teams (though they’re still listed in order), the organization itself uses the site for determining at-large bids to its annual tournament for over 14-year-olds.

The rankings have become such a factor in youth hockey that it drives many of the micro-decisions parents and coaches are forced to make, whether that’s running up a score or choosing what team to play for.

Not only do rankings affect scheduling and strategy, they’re also often the reason hockey families drive hours upon hours each week or even move to new cities in order to play on a better team.

“You see kids slide from city to city,” says Tim Okicki. “They might be on your team, but now they want to go play for this other team. It creates this one-foot-out-the-door mentality.”

(Photo courtesy The National Basketball Academy)

As High school came around, Samantha eventually found a love for tennis again. Her sister,

Sarah, became a mentor who

raved about the team aspect of

collegiate tennis compared to

travel. This year, Samantha committed to Christopher Newport

University, a Division III school

in Virginia.

“Everybody hates this process,” Robertson says. “Even the ones that are the most successful. Once they’re done and playing D-I or whatever, they’re like, ‘God that was awful.’ I’m like, ‘Wow, you were the ones winning and you still hated the process.’ So I feel like that was kind of comforting like misery loves company, or something.”

One simple conversation made a world of difference for the Robertson family. Dad, who played more of a fan role to Robertson’s parent-coach, suggested implementing a reassessment meeting, where Sarah and Samantha could talk openly to their mother.

At least once a season, if not more, mother and daughter would sit at their kitchen table and discuss a few questions: Where are we? Are we still having fun? Is this still what you want?

But the Robertson aren’t alone in reassessing youth sports. Despite exponential growth, the industry is beginning to take a harder look at itself.

“There’s got to be a point that you get to where you’re like, ‘It’s too much,’” says Taylor.

Nearly every coach we spoke to discussed encouraging their athletes to play multiple sports. Many also discussed cutting back the number of games, tournaments and practices as well as the amount of travel.

Coach Jeff George of Force Volleyball, which runs more than 20 teams for 10- to 18-year-olds in Eastlake, is proud that two of the star players on his elite team were also varsity basketball players, which have seasons that bump up against each other.

Force also is limiting practices.

“I do think athletes are starting to overtrain,” he says. “We need to make sure that kids are getting enough rest and recovery. So we cut out about an hour of practice a week. The kids were just getting burned out and looking at it as more of a job than as fun.”

A mental health boon can also come from finding ways to make drills more fun, says George. The Okickis agreed with that assessment. At their summer camps, especially the ones geared toward younger children, they find a game of tag or pool noodle hockey just as athletically viable as other drills but much more mentally stimulating.

Shane Kline-Ruminski, a Cleveland native who played professional basketball in Europe, now runs the National Basketball Academy in eight cities. Ninety percent of his teams are local, meaning they play about six or seven tournaments across Northeast Ohio and, potentially, one trip to Pennsylvania.

“I love giving the kids the opportunity to hang out in a hotel with their friends. It’s a cool experience,” says Kline-Ruminski. “We’ve flown all over the country. It’s just not worth it.”

(Photo courtesy Okicki Hockey)

Are there exceptions? Absolutely. Some basketball players are going to shoot until the sun goes down and then turn on the headlights for some more, and TNBA does send its most elite players to showcases and tournaments to get in front of college coaches. Some volleyball players don’t want to take summers off, which is when Force encourages them to play sand volleyball because the stakes are a little lower and it’s easier on their knees.

“There are those grinders, but they’re choosing to do that,” says T3’s Taylor. “The parents aren’t pressuring them or telling them, ‘You’re going to play varsity football in a few years, you need to be ready.’ It’s kids being kids and having a good time.”

Without question, sports are good for children. Despite stereotypes, athletes tend to do better academically. Numerous studies prove that being active improves physical and mental health in children, and playing team sports improves self- esteem and instills values like teamwork and work ethic. The Mayo Clinic even found that tennis players live a decade longer on average.

Nearly all of the coaches and trainers we spoke to were former athletes who praised the communities they’ve built around sports. The Okicki brothers shared how they still play adult hockey with many of their childhood friends, and how former teammates have found jobs in new cities thanks to the vast network hockey provides. Taylor, who got married in August, chose an old teammate and training partner to be his best man.

But one day, even if the friends remain and even if you play adult rec league, the practices and tournaments and car rides and arguments and failures and triumphs end. Then what remains?

“When I was a kid, I had my share of fun. I was out every weekend, but I think it’s really time for me to just lock in,” says Price. “But what do I do when I’m not playing basketball? I guess I’m really just sitting at the house sometimes. I guess I do wish I had a little bit more other hobbies or other things that I could do. I guess I still need to find that in myself.”

Discover the best tips for maintaining the mental and physical health of today's young athletes.

Dillon Stewart

Dillon Stewart is the editor of Cleveland Magazine. He studied web and magazine writing at Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism and got his start as a Cleveland Magazine intern. His mission is to bring the storytelling, voice, beauty and quality of legacy print magazines into the digital age. He's always hungry for a great story about life in Northeast Ohio and beyond.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5