Remembering Michael D. Roberts: Pioneering Cleveland Magazine Editor and Journalist Dead at 85

by Dillon Stewart | Jan. 6, 2025 | 12:30 PM

Kevin Kopanski

Great magazines aren’t written — they’re edited.

Michael D. Roberts, the founding editor of Cleveland Magazine and a hotshot reporter for The Plain Dealer before that, never let Steve Gleydura forget it. Long after Roberts’s 17 years with the magazine, which began in the early ‘70s, he frequently met the young Gleydura, the only editor to serve at the top of the masthead about as long as Roberts, for hours-long lunches. Roberts, however, craved not a sandwich but a story. He’d pepper Gleydura with questions: “What are you hearing? What are people talking about? What are you working on? What’s the big story?” His hunger was insatiable.

“He never stopped being an editor,” Gleydura says. “I don’t know of someone who knew the city, cared about the city as much as Mike did.”

Roberts, whose leadership at Cleveland Magazine served as a nationwide model of what a city magazine could be and a reporter who witnessed firsthand some of the biggest moments of the turbulent ’60s, died this week after a long health battle, according to multiple friends and colleagues. His loss is one of a pioneering storyteller, a sharp critical voice and wealth of knowledge about the moments and movers who shaped Cleveland. He was 85 years old.

Bold and unafraid, Roberts embodied the archetype of an old-school newsman, drinking beer in the reporter bars and swearing like a, well, journalist. He relished the days when his front page stories earned him the right to “f—--- smirk and be a real asshole” to the rival reporters who gathered each night at the Headliner Cafe on Superior Avenue and East 17th Street — and those opportunities came often. But for those who worked under his editorship, he was an indispensable mentor who always pushed for more and shaped some of the greatest writing and reporting in the golden era of Cleveland journalism.

While suffering from polio in childhood, Roberts filled his time reading The Cleveland Press. He dreamt of becoming a journalist for the daily. Instead, in 1963, he started as a cub reporter at rival The Plain Dealer, which sent him on assignment to Washington, the Middle East and Vietnam, during the war. He interviewed President Richard Nixon, arrived in Vietnam during the Tet Offensive and was on the ground in Saigon when the national police chief of South Vietnam executed a Vietcong fighter in 1968, the iconic photo of which changed the tide of the war.

“He was a guy who could walk across the street and stumble across a story,” says Ed Walsh, who served as associate editor for Cleveland Magazine and was a confidant of Roberts’ in his later years. “He was really quite a force.”

Back in Cleveland, where he’d eventually serve as the paper’s city editor, he covered Carl Stokes’s mayoral campaign, Art Modell, the second Sam Sheppard trial and the Kent State University shooting. During the Hough Riots, he wrote with his signature poignant pen, that "even the shock of the Hough Riots failed to awaken the town's slumbering political and civic leaders, who had trouble fathoming what had gone wrong. The business community was in denial and the politicos were casting seeds of blame." He reported on the ground during the uprising and paused an interview while the owner of the Seventy-Niner Cafe beat an armed looter with a bat.

“When you’re in these things, stay near the door,” he later advised.

Readers today can see the events of the ’60s through the young reporter’s eyes in his books Hot Type, Cold Beer and Bad News and Thirteen Seconds, which is co-bylined with acclaimed Cleveland native Joe Eszterhas and follows the events of the Kent State Shootings.

“I was lucky to come at a time when The Plain Dealer was trying to change, trying to get its sh– together. For a while, it did,” he said. “I was overwhelmed by being there. We had about 50 to 60 reporters, a number of editors. You’re [all] talking about how the city works.”

In April 1972, 32-year-old advertising copywriter Lute Harmon Sr. published the first issue of Cleveland Magazine. The cover featured an illustration of Dennis Kucinich, nicknamed “Denny the Kid,” during a failed run for the U.S. House of Representatives, five years before he’d become mayor of Cleveland. A few months later, the magazine’s editor Gary Griffith quit.

“For some reason he did not like the 7-day work week,” says Lute Harmon Sr., founder and former publisher of Cleveland Magazine and chairman of parent company Great Lakes Studios. “As publisher, I had to find an editor and it became apparent no established journalist wanted to work for a startup.”

Logic would put Roberts in that camp. City editor for The Plain Dealer was a prestigious title, especially for a man still in his 20s. In fact, Roberts didn’t give the magazine much of a chance to survive, but when Harmon reached out, he agreed to dinner (and some drinks, it seems).

“He spent three hours telling me what was wrong with the publication before the restaurant manager told us he was closing,” says Harmon. “The next morning when Mike called to ask what had transpired at dinner I congratulated him on accepting the position of editor of Cleveland Magazine.”

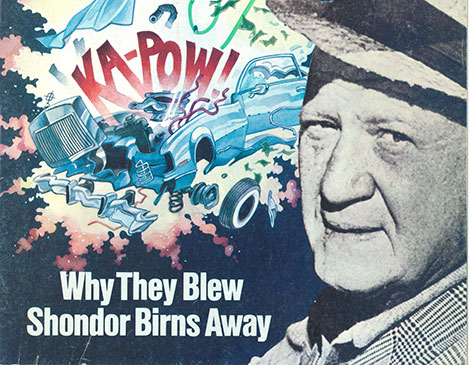

Within months, he put together a “team of journalists that were writing stories about people and issues that Cleveland had never seen before,” says Harmon Sr. That list of writers and editors included or grew to include Ned Whelan, Don Robertson, Jim Wood, Terry Sheridan, Brent Larkin, Frank Kuznik, Gary Diedrichs, Greg Stricharchuk, Tom R. Halfhill, Joe Eszterhas, Dick Feagler and many more. Roberts continued to write, too, albeit selectively, when he just couldn’t pass the story up. In July 1975, for example, he wrote the cover story “Why They Blew Shondor Burns Away.”

“Mike was relentless as an editor, and working for him was not for the faint of heart, but damn did we have fun,” says Richard Osborne, who served as managing editor from 1979-1982 and later as the editor of Ohio Magazine. “He attracted Cleveland's best writers who were masters of that art. We learned from Mike more than any journalism course could ever teach you. He had a huge influence on that generation of young journalists.”

The small-but-mighty team couldn’t keep up with the volume of the local newspapers, and they didn’t try. Instead, rooted in the muckraking era that preceded them and inspired by the literary new journalism movement of Tom Wolfe that was en vogue at the time, the staff worked to tell stories that no one was telling in ways that no one was telling them. Often, he’d sit at editorial meetings and ask, “What’s the hardest story we could do this week?”

“He was a bit of a pugilist when it came to journalism,” Walsh says. “He wanted to fight with the best of them.”

Often, he brought those ideas to the table. The magazine’s coverage pissed off local leaders like Akronite and Cleveland Indians owner Dick Jacobs and Bay Village native George Steinbrenner, and the city was better for it. Mobsters, too. Ray Ferritto, the hit man for the Mayfield Road Mob who killed Danny Greene in 1977, reportedly identified the gangster from a photo in Cleveland Magazine. Roberts fostered a tight-knit newsroom, and he always demanded more and deeper reporting. A wordsmith in his own right, the editor meticulously helped writers shape and massage their copy, poking holes in sentences that were unclear and pushing them to get to the point. Often, stories became a team effort, with staffers doing everything from making extra calls to staking out a subject’s workplace.

“That's the kind of stuff we regularly did,” says Osborne. “It was a group effort, and everybody was caught up in it. You certainly felt a tremendous sense of satisfaction when you had the whole town talking. We were extremely proud of what we accomplished.”

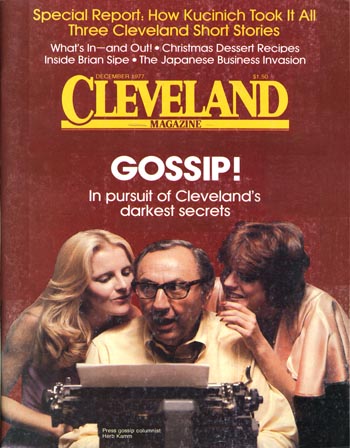

Slowly but surely, the publication — along with a few others, including New York in 1968, Boston in 1971, Texas Monthly in 1973 and Philadelphia, which was founded in 1908 but saw new life in this time thanks to a series of National Magazine Awards — became a model for city publications that would eventually spread to nearly every region in the country. Along with Whelan, who became Cleveland Magazine’s star writer and would later succeed Roberts as editor, the magazine covered power, art, money, gossip, dining, culture, drugs, health and the Best of Cleveland.

“Mike helped invent the genre of city magazines,” says Osborne. “I don't think there is any question that the best journalism in Cleveland of that era was put out by Cleveland Magazine.”

In 1980, Harvard University’s Nieman Reports called Cleveland Magazine "a gritty magazine in a town widely known for its gritty reality" and named it one of the country’s best.

“We’d attained a sense of legitimacy as a publication that was respected in the city,” Roberts told Cleveland Magazine in 2022. “It was joyful.”

Fifty years since the first issue of Cleveland Magazine, the writing, reporting, photography and design in those early issues remain just as sharp and hilarious, sometimes questionable but always groundbreaking — essential to the history and understanding of this city.

Regrettably, not all of our early stories have been digitized. We’ve tried, but it’s an arduous process, the surface of which we’ve only scratched. Perhaps one day artificial intelligence will help make the dream of publishing the entire collection a reality. Recently, we launched an Instagram and Facebook account @oldclevelandmagazine to honor these covers and stories.

But those archives remain in Cleveland Magazine’s office in Playhouse Square’s Hanna Building, our third home after Emerson Press on Chester Avenue and then the Keith Building. One of the great privileges of my job is getting to dig through those early issues. I never got to meet Roberts, as he was in poor health when I took over the editorial direction of the magazine in 2022. Yet, feeling and smelling the musty, 50-year-old pages offers a brief portal to a world, both in Cleveland and in media, that no longer exists but shapes who we are today. These stories, designs, illustrations and photos, in the shadows of which I’ll always remain, remind me of the gravity and weight that comes with editing a nearly 53-year-old publication.

“The magazine of that time really left a wonderful and important legacy for what the city was like, what the people were like, what the powerful were like, what the weak were like,” says Walsh. “Mike's loss really is a loss, and something is lost with him, and that was an era of journalism where you really went after the tough stories, and you took on the tough challenges, and you came up with some really great stuff. I think the contribution of the magazine to the city, it's really a terrific legacy.”

The magazine has evolved over the years, and each editor has put their own stamp on it. Roberts’ gritty news features gave way to celebrity profiles, then service journalism and, now, a digital-first ethos. I’m sure some of these approaches dismayed him. (Ask Gleydura, who says he always heard when Roberts didn’t like something he’d do.) Yet, all of these iterations existed within the framework he created. Plus, he sure as shit didn’t seem like the type of guy who would let someone else define his vision. Why should any of us be different?

But in each of those eras, Michael D. Roberts’s 17 years at Cleveland Magazine, his dedication to smart, longform journalism and serving the people of Cleveland, were and remain a blueprint. Gleydura even hung a photo of Roberts, Harmon Sr. and the rest of their staff above his desk as a reminder of the magazine’s roots.

“It was all them with big steins of beer in their hands. Just very ‘70s Cleveland Magazine,” he says. “Whenever I thought, What should we do? It was always like the spirit of them were watching over me.”

Today, we work to champion the Best of Cleveland, but we also want our coverage to help build an even better Cleveland and to highlight those who are working toward that cause. Though he showed his love for the city in every stroke of his pen and punch of his typewriter, Roberts didn’t believe in blind boosterism and neither do we. To him, the reader made Cleveland great, not the politicians or businessmen who had something to gain by the magazine’s positive coverage.

“It is important that the city have an honest view of itself and not the Downtown bullshit guys,” he said. “We’ve got to be more thoughtful about who we are, where we’re going and not live in a silly world.”

In 2018, Roberts told Cleveland Magazine that he worried about the future of the media.

“It doesn’t appear to me as if, financially, there’s enough support here for decent journalism,” he said. “People are trying. But you can’t do it without money. But that doesn’t mean you give up. Sharpen your skills, deal with the issues.”

Fifty-three years ago, he joined what he saw as a doomed publication, yet his talent and tenacity overcame those long odds for success. So, Mike might be gone, but thanks to him, Cleveland Magazine is still here, sharpening our skills, dealing with the issues and never giving up on his city.

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Dillon Stewart

Dillon Stewart is the editor of Cleveland Magazine. He studied web and magazine writing at Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism and got his start as a Cleveland Magazine intern. His mission is to bring the storytelling, voice, beauty and quality of legacy print magazines into the digital age. He's always hungry for a great story about life in Northeast Ohio and beyond.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5